Death was everywhere in the 1800s. Honestly, it’s hard for us to grasp today, but in the Victorian era, losing a child to scarlet fever or a spouse to consumption was just... a Tuesday. Life was fragile. Because of that, Victorians developed a relationship with grief that looks, to our modern eyes, a little bit like a horror movie.

Enter the world of Victorian post mortem photographs.

You’ve probably seen them while doom-scrolling through "creepy history" threads. You know the ones: a stiff-looking child standing up, supposedly held by a metal pole, or a family sitting for a portrait with a sister who has "painted-on" eyes. It makes for a great viral tweet.

The problem? Most of those "facts" are total nonsense.

✨ Don't miss: Why The Gospel to Every Creature John Darnell Still Resonates Today

The internet has a weird obsession with making the Victorians look more macabre than they actually were. If you want the real story of how these people mourned, you have to look past the creepypasta and into the actual science of 19th-century photography.

The Myth of the "Meat Puppet" Stand

Let’s kill the biggest lie first.

There is a widespread belief that Victorian photographers used heavy-duty metal stands to prop up dead bodies so they could "stand" for one last photo. People point to visible metal bases behind the subjects as "proof."

That is 100% false.

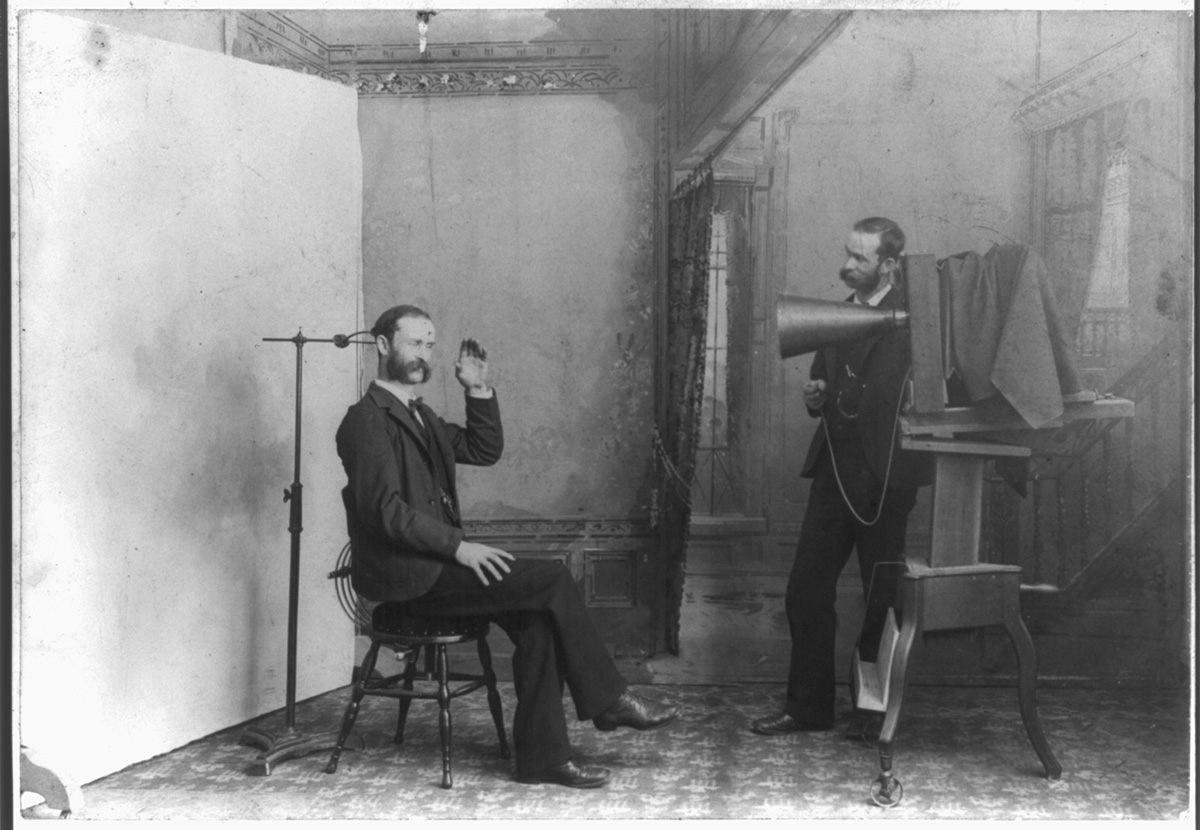

Those stands were actually posing stands, and they were used exclusively for the living. Early photography, like the daguerreotype, required incredibly long exposure times. We’re talking anywhere from thirty seconds to a full minute. If you breathed too hard or blinked, you were a blurry mess. The stand was there to help a living person keep their head still.

Think about the physics. A human corpse is dead weight. It’s either limp or locked in rigor mortis. A flimsy cast-iron rod—the kind used back then—could no more hold up a 150-pound body than a microphone stand could hold up a sofa. If you see a stand in a photo, it is a guarantee that the person in front of it was very much alive.

How Victorian Post Mortem Photographs Actually Looked

Real memorial photography wasn't about trickery. It was about "The Last Sleep."

The Victorians were deeply sentimental. They didn't want a "Weekend at Bernie's" situation; they wanted a peaceful image of a loved one at rest. Most authentic post mortem photos follow a few specific patterns:

- The Bedside Pose: The deceased is usually lying in bed, eyes closed, appearing as if they are napping.

- The Coffin Portrait: Especially later in the century, it became common to just photograph the person in their casket surrounded by flowers.

- The Parental Embrace: This is the heart-breaking stuff. You’ll see a mother holding a baby that looks perfectly still. Because the baby was dead, they were often the only one in the photo who was perfectly in focus, while the grieving mother might be slightly blurred from shaking.

Photographers like Southworth & Hawes in Boston were famous for these. They didn't try to hide death; they tried to make it look beautiful. They called photography "the mirror with a memory."

Why did they even do this?

It sounds morbid, but for many families, the post mortem photograph was the only image they ever had of that person. Photography was expensive. You didn't just take selfies. If your toddler died at age three and you never had the money for a portrait while they were alive, the "death photo" was your only way to remember their face.

📖 Related: New Britain CT USA: Why the Hardware City Is Suddenly Growing Again

It was a treasure. People kept these in lockets or displayed them on the mantel. They weren't trying to be "edgy" or dark; they were just desperate not to forget what their child looked like.

Spotting the Fakes (The "Creepy" Factor)

If you're browsing eBay or Pinterest, you're going to see a lot of "post mortem" listings that are just regular Victorian portraits. Here’s how you can tell the difference.

The "Painted Eyes" Trap

People love to claim that Victorians painted eyes onto the closed eyelids of corpses. While some photographers did retouch photos with a bit of pink on the cheeks to make the person look less "waxy," the idea of painting wide-open eyes was extremely rare and usually looked terrible. If the eyes look "off," it’s more likely a living person who moved their eyes during the long exposure, causing a ghostly blur.

The Hands Clue

Check the hands. Sometimes, blood pooling (lividity) would make the hands of a deceased person look much darker than their face. However, even this isn't a perfect science. A lot of living Victorians had rough, tanned, or dirty hands from manual labor that looked dark in black-and-white photos.

The "Hidden Mother"

You’ve probably seen those weird photos where a woman is covered by a rug or a curtain while holding a baby. People claim the baby is dead. Actually, it’s the opposite. It was almost impossible to get a living, squirming baby to sit still for 40 seconds. The "hidden mother" was there to pin the kid down so the photo wouldn't blur. If the baby was dead, you wouldn't need to hide the mother—she’d just hold the child openly.

The Cultural Shift: Why We Stopped

By the early 1900s, this practice started to fade.

The invention of the Kodak Brownie camera in 1900 changed everything. Suddenly, photography was cheap and "instant." Families started taking photos of their kids while they were playing, eating, and living. You didn't need a memorial photo anymore because you already had a box full of snapshots from the last ten years.

Also, the medical world changed. We moved death out of the home and into hospitals. We became "death-denying." What was once a natural part of a family’s grieving process became something "gross" or "unhealthy."

Identifying Authentic Pieces

If you are a collector or a history buff, look for these specific indicators of a real memorial photo:

- The subject is in a casket or lying on a cooling board.

- There is clear funeral iconography (willow trees, inverted torches, or mourning wreaths).

- The caption or "carte de visite" back explicitly mentions a date of death.

- The "Sunken Eye" look: After death, the eyes sink slightly into the sockets, creating a specific shadow that is very hard to fake with a living model.

Actionable Insights for History Enthusiasts

If you want to see the real deal without the internet myths, check out The Thanatos Archive. It is one of the most comprehensive collections of authentic memorial photography in the world. You can also look into the work of Dr. Stanley Burns, whose book Sleeping Beauty is basically the gold standard for this subject.

When you look at these photos, try to put yourself in the shoes of a parent in 1870. Don't look for the "creepiness." Look for the love. These weren't props; they were daughters, sons, and spouses.

If you're researching a specific family photo and think it might be a post mortem, check the focal point. If the "deceased" person is the only one in the frame who is 100% sharp and crisp, while everyone else has a tiny bit of "motion blur," you might actually be looking at a genuine piece of Victorian mourning history. Otherwise, it’s probably just a very bored, very tired, but very much alive Victorian.