You know that feeling when you're halfway through a movie and the genre suddenly flips? One minute it’s a sweeping romance, the next it’s a high-octane heist. That’s basically the Violin Concerto Samuel Barber in a nutshell. It is one of the most beautiful, frustrating, and misunderstood pieces of music ever written in America.

People love to talk about the "scandal" behind it. You’ve probably heard the version where a violinist rejected it because it was too easy, then rejected it again because it was too hard. It makes for a great story.

Honestly? Most of that is total fiction. Or at least, it’s a very distorted version of the truth.

The Soap Money and the "Unplayable" Finale

Let’s go back to 1939. Samuel Barber was 29 and starting to feel the heat of success. He’d already written the Adagio for Strings, which basically made him a superstar in the classical world. Then comes Samuel Fels. Fels was a soap tycoon—think Fels-Naptha—and he wanted a concerto for his ward, a young violinist named Iso Briselli.

Fels offered Barber $1,000. In 1939, that was a massive payday. Barber took the cash, headed to Switzerland, and started writing.

He knocked out the first two movements and sent them over. Briselli liked them, but his teacher, a guy named Albert Meiff, absolutely hated them. Meiff wrote a stinging letter to Fels, basically saying the music was "not violinistic" and too simple. He wanted more flash. More fireworks.

Barber, probably a bit annoyed, eventually turned in the third movement. It was a four-minute explosion of notes. A moto perpetuo.

The legend says Briselli tried to play it, threw his hands up, and said it was "unplayable." But the real history—uncovered in letters released much later—shows that Briselli actually thought the third movement just didn't fit artistically. He felt it was too lightweight compared to the soul-crushing beauty of the first two parts.

To prove it could be played, Barber got a student at the Curtis Institute, Herbert Baumel, to learn the finale in just a few hours. Baumel shredded it in front of a small committee, proving it wasn't a finger-breaker for the sake of being impossible.

✨ Don't miss: Occam's Razor: Why House Series 1 Episode 3 Is Still the Show's Greatest Lesson

In the end, Briselli walked away. He didn't play the premiere. That honor went to Albert Spalding in 1941.

Why the Music Feels Like Two Different Worlds

If you listen to the Violin Concerto Samuel Barber today, the first thing you’ll notice is the opening. There’s no big orchestral buildup. No "get ready, here comes the star" moment. The violin just... starts. It’s like walking into a room and catching someone mid-sentence.

The First Two Movements: Pure Heartbreak

The first movement, Allegro molto moderato, is lush. It’s neo-Romantic, which is a fancy way of saying Barber wasn't afraid to write a melody you could actually hum. It feels like a late summer afternoon. Warm, a little nostalgic, but with a weird "scotch snap" rhythm that keeps it from getting too sentimental.

Then there’s the second movement. The Andante.

It starts with this long, lonely oboe solo. It is arguably one of the most beautiful things ever written for the instrument. When the violin finally enters, it doesn't take over; it joins the conversation. There’s a moment in the middle where everything gets dark and dissonant, like a sudden storm, before it settles back into that quiet, aching peace.

The Finale: The "Wasps" in the Jar

Then comes the third movement. Presto in moto perpetuo.

It is a total shock. After 20 minutes of lyrical dreaming, the violin turns into a machine. It’s a relentless stream of triplets that never stops for breath. It’s jittery. It’s aggressive. It’s brilliant.

A lot of critics at the time—and even some today—agree with Briselli. They think the ending feels tacked on. It’s like finishing a five-course gourmet meal with a shot of espresso and a slap in the face.

But here’s the thing: that contrast is exactly why it works. It captures that 1939 anxiety. You have this old-world beauty being chased down by the frantic, mechanical energy of the modern age. Barber was writing this as World War II was literally breaking out in Europe. He had to flee Switzerland because of the Nazi threat. Of course the music sounds like it’s running for its life.

How to Actually Listen to the Barber Concerto

You don't need a music degree to "get" this piece. But if you want to really hear what’s happening, pay attention to these three things:

💡 You might also like: Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2: Why the Battle of Hogwarts Still Hits Different

- The Oboe/Violin Hand-off: In the second movement, listen to how the violin "wakes up" after the oboe solo. It’s like someone waking up from a dream and trying to remember the melody they just heard.

- The Piano: Barber actually included a piano in the orchestra. It’s subtle, but it adds a percussive, brittle edge to the sound that sets it apart from 19th-century concertos.

- The Tempo: When you listen to the third movement, check out different recordings. Hilary Hahn plays it at a speed that seems physically impossible, while older recordings might be a bit more measured. The faster it goes, the more "dangerous" it feels.

Why It Still Matters in 2026

The Violin Concerto Samuel Barber is now a staple. Every major violinist plays it. It’s funny because, for a while, the "serious" academic composers looked down on Barber. They thought he was too traditional, too "easy" on the ears.

But guess what? Audiences didn't care. They wanted to feel something.

Today, we see Barber as a bridge. He kept the soul of the Romantic era alive while pushing it into the jagged, nervous energy of the 20th century. He proved that you could be "modern" without being "ugly."

Actionable Listening Guide

If you want to dive deeper into the world of Samuel Barber, don't stop at the concerto. Here is how you should explore his work to get the full picture:

- Listen to the 1941 Premiere Vibes: Find a recording by Isaac Stern or Gil Shaham. They capture that classic, lyrical "Americana" sound perfectly.

- Compare the Finale: Listen to James Ehnes and then Hilary Hahn. Notice how the character of the piece changes just by the speed of the bow.

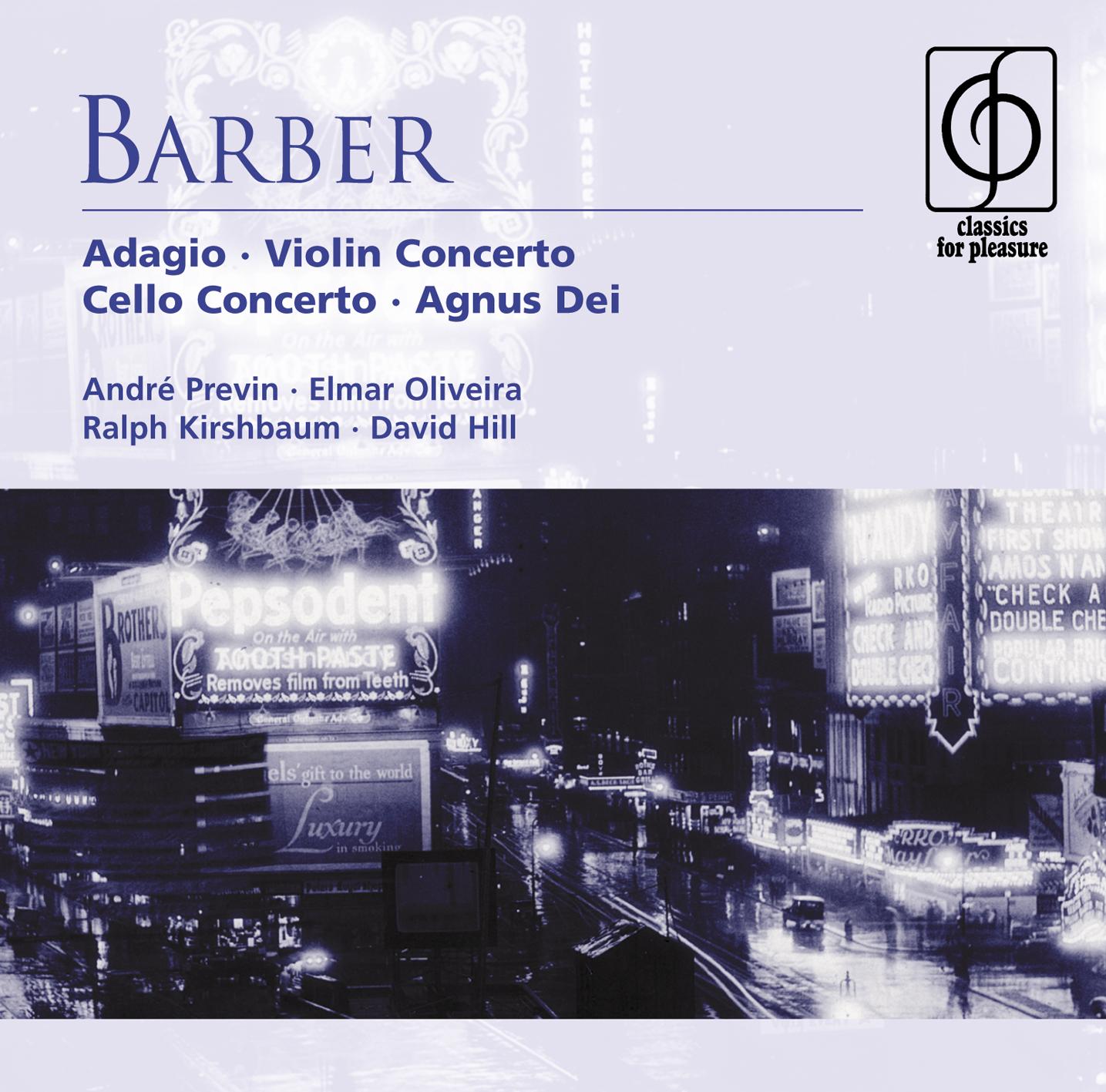

- The "Sequel": After the violin concerto, listen to Barber's Cello Concerto. It’s much thornier and more complex, showing how he evolved after the Fels/Briselli drama.

- The Vocal Connection: Barber was a trained singer. Listen to his Dover Beach. You’ll hear why his violin writing always feels like it’s "singing"—he literally wrote for the instrument the way he would write for a human voice.

The real "secret" of the Violin Concerto Samuel Barber isn't the drama of the commission. It's the fact that it survived the drama at all. It was almost buried by a disgruntled teacher and a nervous patron, but the music was just too good to stay hidden. It’s a 25-minute masterclass in how to hold onto beauty while the world is moving too fast to keep up.

👉 See also: To Ramona: What Most People Get Wrong About Dylan’s Gentlest Kiss-Off

To get the most out of your next listen, try to find a live performance video where you can see the soloist's right arm during the third movement. The sheer physical stamina required for those four minutes is enough to make anyone appreciate why Barber refused to change a single note.