You’re sitting there reading this, and without even thinking about it, your heart just thumped about seventy times in the last minute. Your lungs expanded. A little valve in your stomach probably clamped shut to keep acid from splashing up into your throat. You didn’t command any of that. If you had to manually remember to beat your heart every second of every day, you’d be dead in five minutes—probably the first time you got distracted by a text message. This is the wild reality of voluntary muscles and involuntary muscles. It’s a constant, silent tug-of-war between the things you control and the things your brain stem handles so you don't have to.

Think about your biceps for a second. That's the classic example. You want to pick up a coffee mug, your brain sends a zippy electrical signal down the spinal cord, and—boom—the muscle contracts. That is voluntary. But then there’s the smooth muscle lining your intestines, pushing breakfast along through a process called peristalsis. Try telling your small intestine to speed up. It won't listen. It doesn't care what you want.

The Puppet Strings: How Voluntary Muscles Actually Work

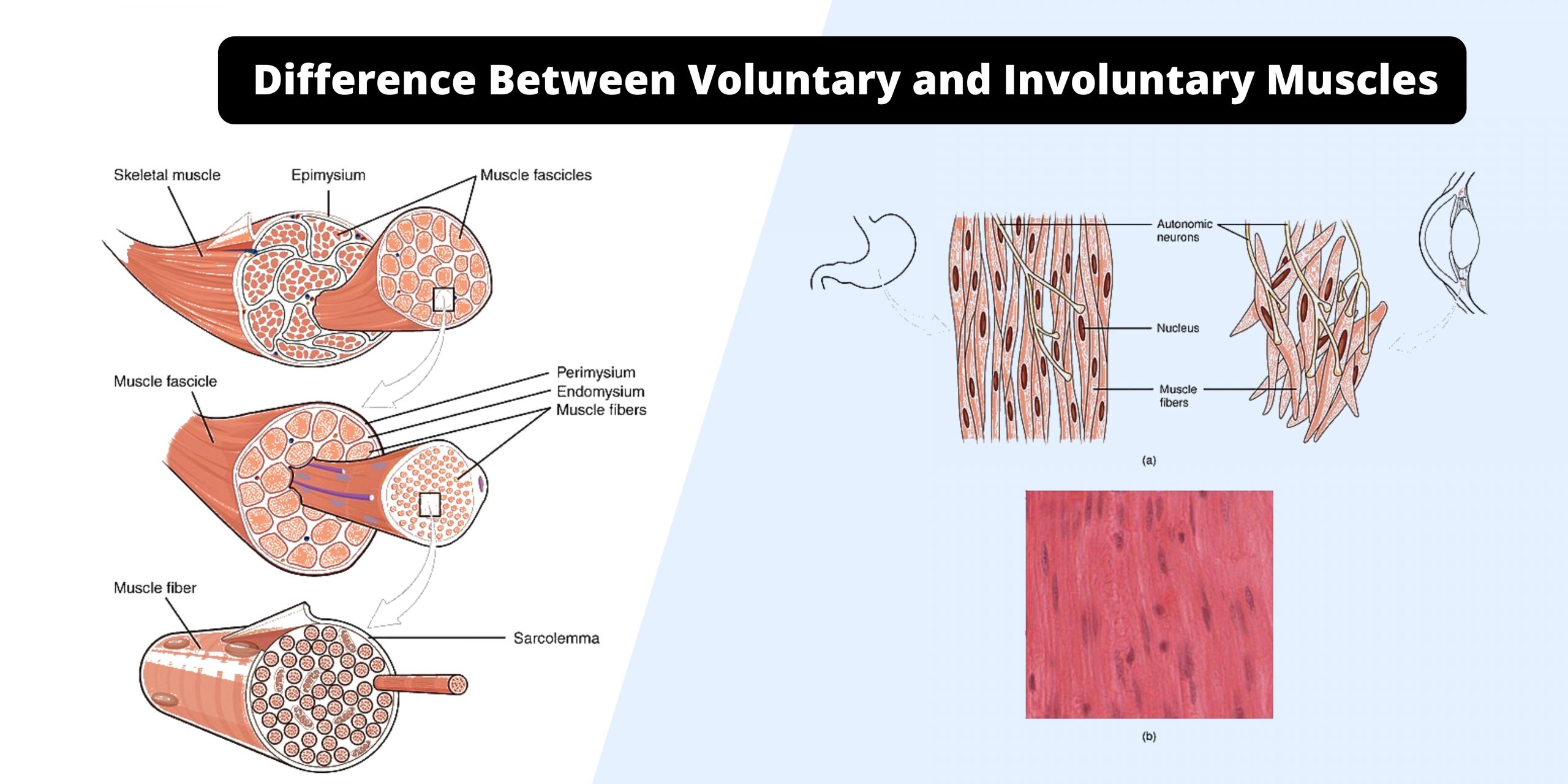

When we talk about voluntary muscles, we’re mostly talking about skeletal muscles. These are the ones attached to your bones by tendons. They are the reason you can walk, dance, or type "u up?" at 2 AM. These muscles are striated, meaning if you looked at them under a microscope, they’d look like a bunch of tiny stripes or bands. These bands are actually overlapping filaments of actin and myosin. When they slide past each other, the muscle shortens.

Here is the kicker: even "voluntary" muscles aren't always under your conscious thumb. Ever had a muscle twitch in your eyelid when you’re stressed? Or that weird "hypnic jerk" right as you’re falling asleep where your leg kicks out? Those are skeletal muscles acting like they’ve gone rogue. Normally, though, the somatic nervous system is the boss here. It’s a direct line from the motor cortex in your brain to the neuromuscular junction.

Biologically, these muscles are designed for power and speed, but they tire out fast. They need a lot of ATP (adenosine triphosphate) to keep going. If you sprint for 400 meters, your voluntary muscles are going to start screaming because of lactic acid buildup. They are high-maintenance. They require rest. They are the "sprinting" portion of your internal workforce.

The Fast-Twitch vs. Slow-Twitch Nuance

Not all voluntary tissue is created equal. You’ve got Type I fibers (slow-twitch) that are great for endurance, like keeping your back straight while you sit. Then you’ve got Type II (fast-twitch) for explosive movement. Most people think they can just "will" their muscles to do anything, but your genetic makeup of these fibers determines if you're built more like a marathoner or a powerlifter. It’s voluntary, sure, but within the limits of your own biology.

The Auto-Pilot: Why Involuntary Muscles are the Real Heroes

Involuntary muscles are the quiet professionals. They don’t need a pep talk. They don't need you to remind them to work. There are two main types here: smooth muscle and cardiac muscle.

Smooth muscle is everywhere. It’s in the walls of your blood vessels, helping to regulate blood pressure by constricting or dilating. It’s in your respiratory tract. It’s even in your eyes—the iris that shrinks your pupil in bright light is a smooth muscle. These muscles are spindle-shaped and, unlike skeletal muscles, they aren't striated. They are slow, steady, and they almost never get tired. They can stay contracted for long periods without burning through massive amounts of energy.

Then there’s the cardiac muscle. This is the unicorn of the muscle world. It’s only found in the heart. It’s striated like a voluntary muscle, but it’s completely involuntary. It has these special structures called intercalated discs that allow electrical signals to pass almost instantly from one cell to the next. This ensures the heart contracts as a single, coordinated unit. If your heart cells didn't talk to each other this way, your heart would just quiver like a bowl of Jell-O—a condition called fibrillation—and you'd be in serious trouble.

The Gray Area: When the Lines Get Blurry

We like to put things in neat boxes. Voluntary here, involuntary there. But the human body loves to mess with our categories. Take breathing, for example. The diaphragm is a skeletal muscle. You can hold your breath. You can breathe faster on purpose. That’s voluntary. But the second you stop thinking about it, your autonomic nervous system takes over. You don't die in your sleep because your brain keeps the diaphragm moving. It’s a hybrid system.

Reflexes are another "glitch" in the system. When you touch a hot stove, you pull your hand away before you even realize you’re burned. Your spinal cord actually processes that movement before the signal even reaches the "thinking" part of your brain. It’s a voluntary muscle performing an involuntary action for the sake of survival.

The Role of the Autonomic Nervous System

The involuntary side is governed by the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS), which splits into the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches.

- Sympathetic: The "Fight or Flight" mode. It tells your involuntary muscles to dilate your pupils and speed up your heart.

- Parasympathetic: The "Rest and Digest" mode. It tells your heart to chill out and your gut to get back to work.

Real-World Consequences: When Muscles Fail

What happens when this balance breaks? It’s not just about being "weak" or "strong." Medical conditions often target one specific type of muscle.

- Myasthenia Gravis: This is an autoimmune disorder that attacks the communication between nerves and voluntary muscles. People might have drooping eyelids or trouble swallowing because the "voluntary" signal isn't getting through.

- Gastroparesis: This happens when the smooth muscles in the stomach stop working correctly, often due to nerve damage from diabetes. The "involuntary" system fails, and food just sits there, refusing to move.

- Cardiomyopathy: This targets the cardiac muscle specifically, making it harder for the heart to pump blood.

Knowing the difference isn't just for biology tests. It's about understanding why your body reacts the way it does. You can train your voluntary muscles at the gym. You can’t exactly "treadmill" your way to a stronger esophagus. However, you can influence your involuntary muscles through things like biofeedback or deep breathing exercises that calm the autonomic nervous system.

The Energy Economy of Your Body

Your body is basically a massive chemical plant that has to decide where to send its resources. Voluntary muscles are expensive. When you’re active, your body shunts blood flow away from the involuntary smooth muscles of the digestive tract and sends it to the skeletal muscles in your legs and arms. This is why you get cramps if you try to swim right after a huge meal. Your body literally can't give 100% to both systems at the same time.

It’s a trade-off. Evolution decided that being able to run away from a predator was more important in the short term than digesting a sandwich.

Moving Forward: Managing Your Muscle Health

Honestly, most of us take these systems for granted until something goes wrong. But there are ways to actually support both sides of the coin.

📖 Related: Finding Luxury Rehabs That Accept Ambetter Without Breaking the Bank

For your voluntary muscles, it’s the basics: resistance training and protein. But don't forget mobility. Skeletal muscles that aren't stretched or moved through their full range of motion get "sticky" due to fascia buildup.

For your involuntary muscles, it’s more about lifestyle. Your heart needs cardio, obviously. But your smooth muscles—especially in your gut—need fiber and hydration. Dehydration is one of the fastest ways to mess with smooth muscle function, leading to everything from headaches (blood vessel constriction) to digestive backups.

Practical Steps for Better Function:

- Prioritize Electrolytes: Magnesium, calcium, and potassium are the "battery acid" for muscle contraction. Without them, both voluntary and involuntary muscles start to cramp or misfire.

- Check Your Posture: Constant tension in voluntary muscles (like your neck and shoulders) can trigger a sympathetic nervous response, keeping your "involuntary" system in a state of high stress.

- Vagus Nerve Stimulation: Techniques like cold exposure or humming can stimulate the vagus nerve, which helps regulate the involuntary muscles of the heart and digestive tract.

- Vary Your Movement: Don't just do the same bicep curls. Use functional movements that force your skeletal muscles to stabilize your core, which bridges the gap between conscious control and automatic stability.

Understanding the split between voluntary muscles and involuntary muscles gives you a better map of your own health. You realize that while you're the captain of the ship, there's a whole crew in the engine room working 24/7 without a single command from you. Treat the crew well, and the ship stays afloat.