You've just filed a lawsuit in federal court. Now comes the part everyone hates: service of process. Usually, that means hiring a guy in a trench coat to hunt down the defendant and hand them a stack of papers. It’s expensive. It’s aggressive. Honestly, it’s often totally unnecessary because of Rule 4 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP).

Most people don't realize that the "standard" way of serving someone—personal service—is actually a fallback. The courts actually prefer it if you just ask the defendant to play ball. This is the waiver of service federal court process. It sounds like you're giving up a right, but you're actually just streamlining the bureaucracy.

The "Duty to Avoid Unnecessary Costs"

Federal judges don't like waste. Rule 4(d) explicitly states that individuals and corporations have a duty to avoid unnecessary expenses of serving a summons. If you’re the defendant and you refuse to waive service without a "good cause," the judge is going to make you pay for it. Literally. You’ll end up footing the bill for the process server the plaintiff had to hire because you were being difficult.

I’ve seen cases where a defendant ignored a waiver request just to be petty, only to get hit with a $1,500 bill for "special process server" fees because they were hiding behind a gated community. The court doesn't find that clever. They find it annoying.

How the request actually works

You don't just call them up. You have to send a specific package. It needs to include the complaint, two copies of the waiver form (Official Form 5), and a prepaid way for them to return it. You also have to give them a reasonable amount of time to respond—at least 30 days if they're in the U.S., or 60 days if they're abroad.

If they sign it, the case moves forward as if they had been served on the day you filed the waiver with the court. No drama. No chasing people through parking lots.

Why Defendants Actually Benefit From Waiving

You might think, "Why on earth would I help someone sue me?"

It’s about the clock.

Normally, once you’re personally served, you have a measly 21 days to file an answer or a motion to dismiss. That is a blink of an eye in legal time. However, if you agree to a waiver of service federal court request, the rules give you a massive extension. You get 60 days from the date the request was sent (or 90 days if you're outside the country) to file your response.

That extra month is gold. It gives your lawyers time to actually research the claims, dig through your files, and maybe even negotiate a settlement before the litigation machine starts grinding at full speed. By "waiving service," you aren't waiving your right to contest the court's jurisdiction or the validity of the lawsuit. You’re just saying, "I have the papers, we can skip the process server."

The Trap: When You Can't Waive

Not everyone can waive service. This is where people trip up. You cannot use this process for:

- The United States government or its agencies.

- Minors or incompetent persons.

- State or local governments (usually).

If you’re suing the FBI or the DMV, don't bother mailing a waiver. You have to follow the strict, specific service rules for government entities, which usually involve serving the U.S. Attorney for that district and the Attorney General in D.C. If you try the "polite" way here, you’ll just waste 30 days and potentially miss a statute of limitations.

✨ Don't miss: McDonald's Then and Now: How a Walk-Up Burger Stand Became a Real Estate Empire

What Happens When They Say No?

Sometimes a defendant just ignores the mail. Maybe they think if they don't sign it, the lawsuit goes away. It doesn't.

If the defendant fails to return the waiver within the time limit, the plaintiff has to move to formal service. But—and this is a big "but"—the court "must" impose the costs of service on the defendant unless they can show a really good reason for refusing. "I didn't feel like it" or "I don't like the plaintiff" are not good reasons.

In Estate of Darulis v. Garate, the court made it very clear: the cost-shifting provision is mandatory. If the plaintiff followed the rules and the defendant didn't have a valid excuse, the defendant pays. This includes the fee for the process server and the attorney's fees for the time it took to file the motion to collect those costs.

Strategy: The "Soft Touch" vs. The "Hammer"

Lawyers often debate which approach is better. Some want to "hammer" the defendant with a process server at their office or home to "send a message." It’s a power move.

But sophisticated litigators know the waiver is often better. Why? Because it sets a professional tone. It tells the judge you are being reasonable. Also, from a practical standpoint, it saves your client's money for the actual fight—the discovery and the trial—rather than wasting it on a guy waiting in a car outside a warehouse for six hours.

The Timing Factor

Wait. Don't wait.

If your statute of limitations is expiring tomorrow, do not rely on a waiver. The act of sending the waiver does not stop the clock. You need to file the complaint first. If the defendant takes 29 days to tell you "no," and your deadline to serve them is on day 30, you are in a world of hurt. Most veteran clerks will tell you: if you’re close to a deadline, skip the pleasantries and go straight to the professional process server.

Actionable Steps for Federal Litigants

If you are a plaintiff starting a case, or a defendant who just got a weird package in the mail, here is how you handle the waiver of service federal court process without losing your mind:

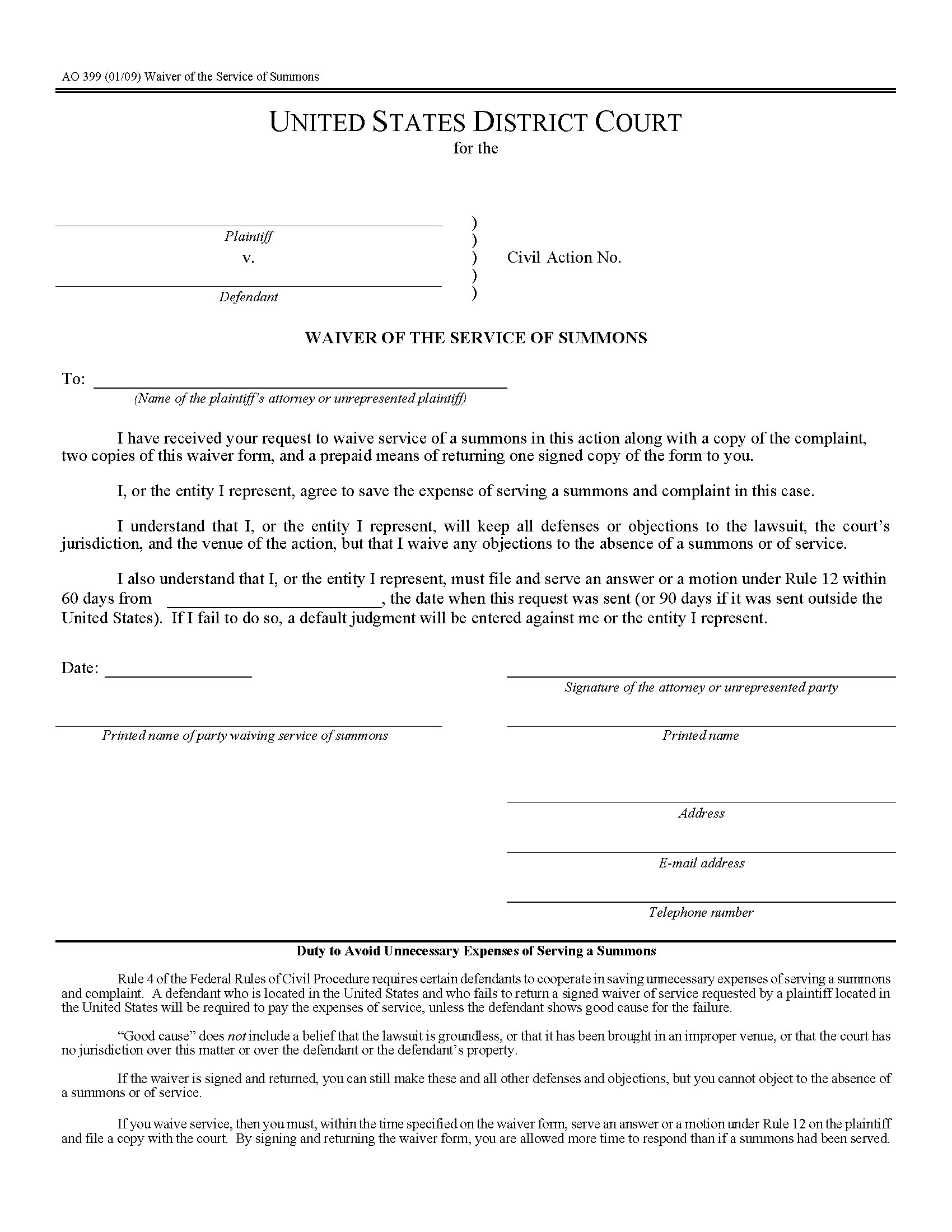

- Check the Form: Plaintiffs, ensure you are using Form 5 (Notice of a Lawsuit and Request to Waive Service) and Form 6 (Waiver of the Service of Summons). If you use your own "custom" letter, the court might not let you recover costs later because you didn't follow the FRCP 4(d) requirements to a T.

- Track the Dates: Defendants, look at the "Date Sent" on the request. Your 60-day window to answer starts from that date, not the date you opened the envelope.

- Send it Right: Plaintiffs should send the request via first-class mail or "other reliable means." While FedEx is great for tracking, the rule is broad. Just make sure you can prove it arrived.

- Don't Waive Jurisdiction: Remember that signing the waiver does not mean you agree that the court has "personal jurisdiction" over you. If you’re a company in Texas being sued in Maine, you can still waive service and then immediately file a motion saying, "Hey, I don't belong in a Maine court."

- Calculate the Costs: If you’re a defendant thinking of refusing, call a process server and ask what they charge for a difficult serve. Then add $500 for the plaintiff’s lawyer to write a motion. That’s the minimum "stupid tax" you’ll pay for refusing to sign.

The waiver process exists to keep the federal docket moving. It turns a potential game of hide-and-seek into a simple exchange of paperwork. Use it when you can, but always keep a process server's number in your back pocket for when things get messy.

Practical Next Steps

- Download the Forms: Go to the official U.S. Courts website (uscourts.gov) and search for AO 398 (Notice of Lawsuit) and AO 399 (Waiver of Service). These are the current standard versions.

- Verify the Address: Before mailing, verify the "Registered Agent" for a corporate defendant through the Secretary of State's website. Mailing to a random office manager won't cut it.

- Calendar the Deadlines: If you send a waiver request, set a reminder for 35 days out. If you don't have the signed form back by then, start the process for formal service immediately to ensure you don't run afoul of the 90-day limit for service under Rule 4(m).