Ever stood in a doctor's office, staring at that laminated paper on the back of the door, wondering if you're "normal"? Honestly, we've all been there. That weight and height chart is a staple of modern medicine, but it’s also one of the most misunderstood tools in the history of health. It feels final. Like a grade on a report card. You look at the grid, find your height, slide your finger over to your weight, and—bam—you’re either in the green or you're "at risk."

But here’s the thing. Bodies are weird.

They’re complicated, messy, and definitely not built to fit into a 1940s insurance actuary’s spreadsheet. Because that’s where most of this started. We use these charts as a shorthand for health, but they often miss the forest for the trees. You might be "overweight" by the chart’s standards while being a marathon runner with a resting heart rate of 50. Or you could be "ideal" but have metabolic markers that look like a disaster zone. We need to talk about why these charts exist, what they actually tell us, and why you should probably stop stressing over the specific number they spit out.

The weird, insurance-based history of the weight and height chart

Most people think doctors invented the weight and height chart to save lives. That's not really how it happened. Back in the early 20th century, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company—yeah, an insurance firm—wanted to figure out how to price their policies. They needed a way to predict who was going to die sooner. They looked at their policyholders, crunched some numbers, and created "desirable" weight tables.

It wasn't about wellness. It was about risk management.

By 1943, these tables became the gold standard. They weren't based on diverse populations or clinical trials; they were based on people who could afford life insurance in the 1940s. Mostly white, middle-class individuals. This historical baggage matters because the "ideal" weight for a 5'10" man in 1943 might not account for the bone density or muscle mass of a modern athlete or someone from a different ethnic background.

Then came the Body Mass Index (BMI). Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian mathematician, developed the formula in the mid-1800s. He wasn't even a doctor! He was a sociologist trying to define the "average man." He explicitly stated that BMI shouldn't be used to judge individual health. Yet, here we are, 150 years later, using his math to decide if we need to go on a diet.

Why the chart fails the "Mirror Test"

You’ve probably seen the meme. Two guys, both 6 feet tall, both 250 pounds. One is a professional bodybuilder with 8% body fat, and the other is a guy who hasn't seen the inside of a gym since 2008. According to a standard weight and height chart, they are both "obese."

The chart is blind to composition. It can't tell the difference between:

👉 See also: Almond Butter and Weight Loss: Why You’re Probably Eating It Wrong

- Muscle: Dense, heavy, and metabolically active.

- Bone Density: Some people literally have "heavy bones"—it's a real physiological thing.

- Visceral Fat: The dangerous stuff around your organs.

- Subcutaneous Fat: The "jiggle" under your skin that is actually relatively harmless compared to visceral fat.

If you’re lifting weights three times a week, your weight will go up. Your jeans might even fit better, but the chart will tell you that you're getting "unhealthier." It’s a paradox that drives people crazy. Take professional athletes. According to standard charts, LeBron James has spent large chunks of his career bordering on the "overweight" or "obese" category. Does anyone honestly think LeBron is unhealthy?

The nuance of "Healthy" ranges

Okay, so the chart isn't perfect. Does that mean we should throw it in the trash? Probably not. For large populations, it's a decent "first look" tool. If a million people are all significantly above the chart's range, statistically, that group will have higher rates of Type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

But you aren't a population of a million. You’re one person.

Medical professionals like Dr. Yoni Freedhoff, a renowned obesity expert, often argue that "best weight" is a better metric than "ideal weight." Your best weight is whatever weight you reach when you’re living the healthiest life you can actually enjoy. If you have to starve yourself and spend four hours a day on a treadmill to hit the "ideal" number on a weight and height chart, that weight isn't healthy for you. It’s unsustainable and mentally taxing.

There's also the "Obesity Paradox." Some studies, including controversial ones published in JAMA, have suggested that people in the "overweight" category (BMI 25-29.9) might actually have lower mortality rates in certain age groups compared to those in the "normal" category. This suggests that having a little bit of a "buffer" might be protective as we age, especially when recovering from serious illness.

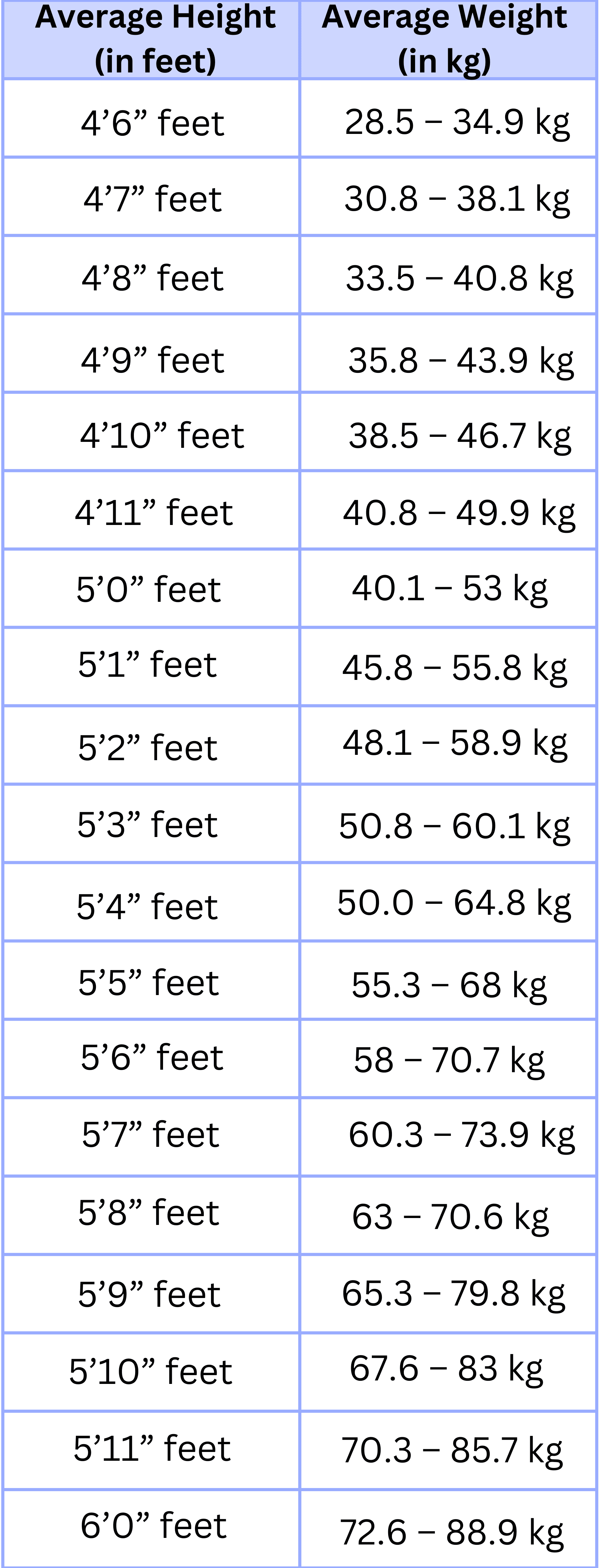

What the numbers usually look like

While I hate giving specific numbers because they vary so much, here is the basic gist of what these charts usually claim for adults. This is prose, not a strict table, because context is everything.

For someone who is 5 feet 4 inches tall, the "normal" range is typically cited between 108 and 132 pounds. If you're 5 feet 10 inches, the chart usually wants you between 129 and 157 pounds. At 6 feet 2 inches, the range jumps to 144 to 176 pounds.

Notice the gaps? They’re huge. Thirty pounds of leeway. And even then, people frequently sit outside those ranges and have perfect blood pressure, perfect cholesterol, and enough energy to hike a mountain.

Age, Gender, and the "Shrinkage" Factor

As we get older, we lose muscle (sarcopenia) and our bones get less dense. We also tend to get a little shorter as the discs in our spine compress. A weight and height chart for a 20-year-old shouldn't be the same as one for a 70-year-old.

Women naturally carry more body fat than men. It’s biological. It’s for hormones, childbearing, and energy storage. Yet many older charts didn't differentiate much between the sexes, or they used "frame size" as a vague way to account for it. If you're a woman with a "large frame," you might be 15 pounds heavier than a "small frame" woman of the same height and be perfectly healthy.

And then there's the "skinny fat" phenomenon. You can be well within the "healthy" range of a weight and height chart but have very little muscle and high levels of internal fat. This is actually quite dangerous because it often goes undetected. People assume they're healthy because the scale is low, so they don't bother eating well or exercising.

Better ways to measure your progress

If the chart is a blunt instrument, what should we use instead? There are several tools that give a much clearer picture of what's going on under the hood.

Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR) is a big one. This measures where you store your fat. If you store it mostly in your midsection (the "apple" shape), you're at a higher risk for heart disease than if you store it in your hips and thighs (the "pear" shape). To find this, you just divide your waist measurement by your hip measurement. For men, a ratio of 0.90 or less is great; for women, it's 0.85 or less.

Waist-to-Height Ratio is even simpler. Try to keep your waist circumference less than half of your height. If you're 70 inches tall, your waist should ideally be under 35 inches. This is often more accurate than BMI because it directly addresses abdominal fat.

Body Composition Scans (DEXA) are the gold standard. They use low-level X-rays to see exactly how much of you is bone, fat, and muscle. They used to be super expensive and only for elite athletes, but many "longevity clinics" or high-end gyms offer them now for about $100. It's eye-opening.

Blood Work. This is the ultimate truth-teller. Your weight and height chart might say you’re "obese," but if your A1C is 5.0, your triglycerides are low, and your HDL is high, you’re metabolically healthy. Period.

The psychological trap of the "Ideal Number"

We need to talk about the mental health aspect of these charts. They can be incredibly triggering. Seeing a "red" or "yellow" zone on a chart at the doctor's office can lead to "weight cycling"—the process of losing weight and gaining it back.

✨ Don't miss: Father Seduced by Son: Understanding the Psychology Behind Complex Family Taboos

Weight cycling is arguably harder on your heart than just staying at a higher weight.

When you focus solely on the chart, you stop listening to your body. You stop noticing that you have more energy, or that you’re sleeping better, or that you can carry all the groceries in one trip. You only care that the little black needle hasn't moved toward the "ideal" zone. That's a losing game.

Actionable steps for a healthier perspective

Forget the "perfect" number. It doesn't exist. Instead of obsessing over where you land on a weight and height chart, focus on these specific, measurable actions that actually change your biology.

- Prioritize protein and fiber. This isn't about restriction; it's about crowding out the junk. Protein builds the muscle that makes the chart "wrong," and fiber keeps your gut microbiome happy. Aim for 30 grams of protein at breakfast. It’s a game-changer for hunger levels later in the day.

- Measure your waist, not just your weight. Get a soft measuring tape. Check your waist once a month at the belly button. If that number is going down or staying steady while you're getting stronger, you're winning, regardless of what the scale says.

- Get a "Functional" Baseline. Can you get up off the floor without using your hands? Can you carry 20 pounds up two flights of stairs without gasping for air? These are "functional" health markers that matter way more for your quality of life than your BMI.

- Request a metabolic panel. Next time you're at the doctor, ask for your fasting insulin and C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation). These tell you what’s happening inside your arteries and cells, which no height-weight grid can ever do.

- Move for "Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis" (NEAT). This is a fancy way of saying "move more throughout the day." Fidget, take the stairs, walk while you're on the phone. This type of movement often burns more calories over a week than a 30-minute gym session.

Ultimately, the weight and height chart is a map. And as the saying goes, the map is not the territory. It’s a reference point, a suggestion, a historical relic that can give us a general idea of where we are. But it shouldn't be the boss of you. Your health is defined by how you feel, how you move, and your internal chemistry—not by a dot on a piece of paper designed by an insurance company eighty years ago.