You think you know what a fairy tale is. You probably picture a princess in a high tower, a talking cricket, or maybe a pumpkin that transforms into a luxury vehicle at the stroke of midnight. Most of us grew up with the sanitized, "happily ever after" versions curated by movie studios. But honestly? That’s barely scratching the surface of this weird, dark, and deeply human genre.

A fairy tale isn't just a story for kids.

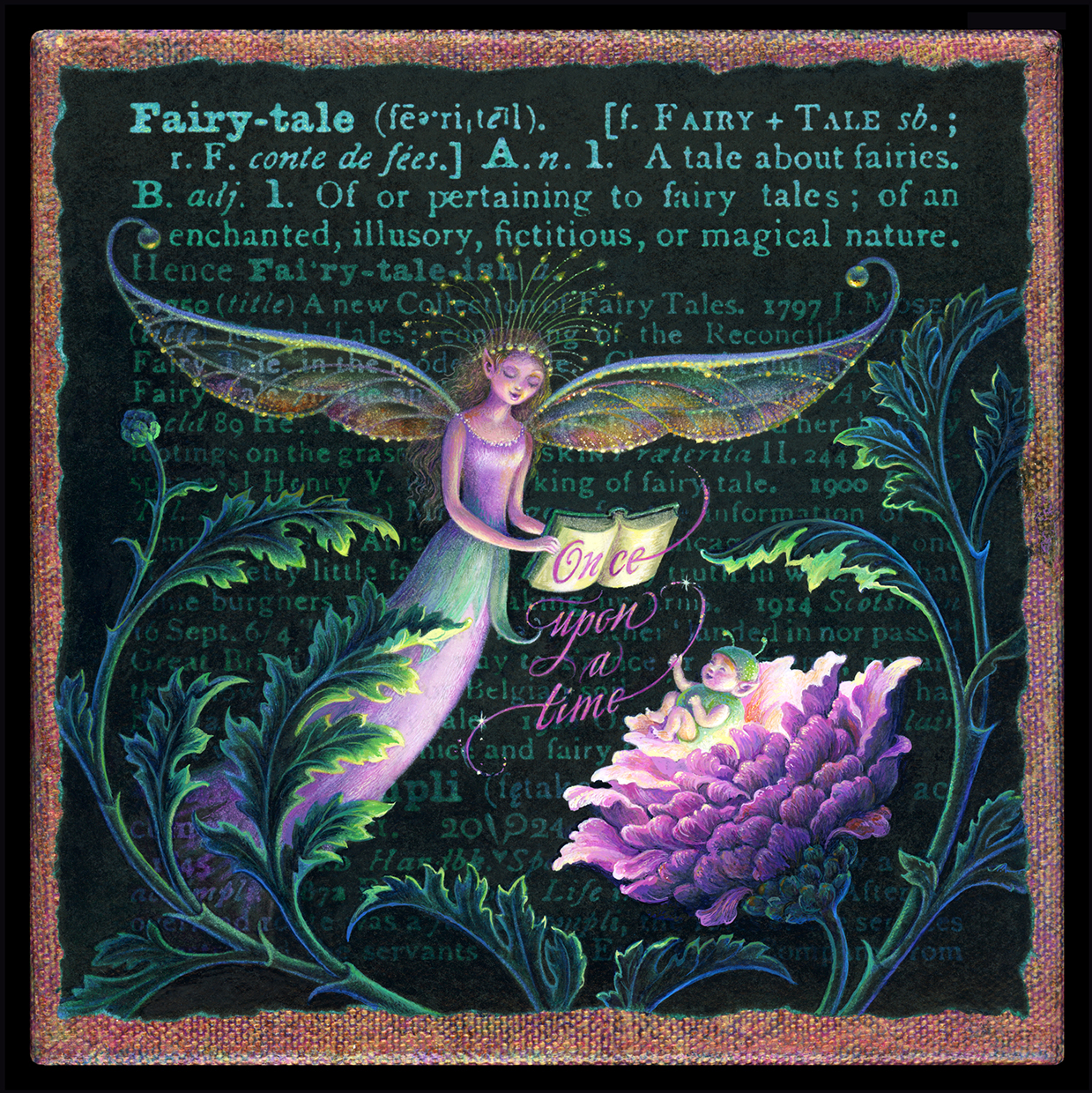

It’s a specific kind of folk narrative that involves magic, transformation, and—crucially—a world where the laws of physics and morality don't always behave the way you expect. It’s not a myth, which usually explains how the world was made. It’s not a legend, which claims to be historical. It’s something else entirely. It’s "Once upon a time."

Defining the Magic: What Makes a Fairy Tale?

Strictly speaking, folklorists like Stith Thompson and Antti Aarne spent decades trying to pin down what a fairy tale actually is. They created the Aarne-Thompson-Uther (ATU) Index, which is basically a giant spreadsheet for every magical story ever told. If you’ve ever wondered why so many stories feel familiar, it’s because they share "motifs."

A fairy tale usually features a "flat" character. This sounds like an insult, but it's not. In a novel, you want deep psychological complexity. In a fairy tale, you get "The Youngest Son" or "The Girl with the Red Hood." They aren't people; they are functions. They move through a world where magic is just... there.

Nobody in these stories asks how the wolf is talking. They just answer him.

The Vladimir Propp Factor

A Russian scholar named Vladimir Propp looked at hundreds of these tales and realized they all follow a weirdly rigid structure. He identified 31 "functions." You start with an absence or a lack (like a starving family), move to a prohibition (don’t go into the woods!), and eventually hit a realization or a wedding.

It’s like a recipe. If you have the right ingredients—a magical helper, a test of character, and a miraculous escape—you’ve got yourself a fairy tale.

The Dark History of the Brothers Grimm

If you go back to the source, things get messy. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm didn't write these stories to tuck children into bed. They were philologists. They were trying to preserve German national identity during the Napoleonic Wars. They collected oral stories from peasants and middle-class friends, and the first edition of Children's and Household Tales in 1812 was gritty.

In the original Cinderella, the stepsisters don't just fail to fit the shoe. They cut off their toes and heels to make it work.

Blood literally leaks out.

The birds peck their eyes out at the end. It’s a far cry from the singing mice and blue dresses we see today. The Grimms actually spent years "cleaning up" later editions because they realized parents were the ones buying the books. They added more Christian morality and removed references to premarital sex, but they kept the violence. Apparently, 19th-century parents were fine with a witch being pushed into an oven, but they drew the line at a princess getting pregnant.

Why We Keep Telling Them

Why do these stories persist? Why is Shrek still a thing? Why did Into the Woods win Tonys?

It’s because what a fairy tale offers is a "safe" way to deal with absolute terror. Bruno Bettelheim, a controversial but influential child psychologist, argued in his book The Uses of Enchantment that fairy tales help children process internal conflicts. The "Evil Stepmother" isn't a literal person; she represents the child's own anger toward their mother when she sets boundaries. By defeating the witch, the child "defeats" their own anxiety.

Whether you buy the Freudian stuff or not, there's no denying that these stories tackle the big, scary themes:

- Abandonment: Think of Hansel and Gretel left in the woods because their parents couldn't feed them.

- Injustice: The youngest, "weakest" brother winning the kingdom.

- Transformation: The idea that you aren't stuck being a beast or a frog forever.

The Global Variation: It's Not All European

We tend to focus on the French (Charles Perrault) or the German (The Grimms) traditions, but fairy tales are a global phenomenon.

Take Ye Xian, a Chinese story from the 9th century. It’s a Cinderella story, but instead of a fairy godmother, there’s a magical fish. When the stepmother kills the fish, its bones become the source of magic. It predates the European versions by hundreds of years.

Then you have the One Thousand and One Nights (The Arabian Nights). These aren't all fairy tales—some are travelogues or erotica—but stories like Aladdin (which was actually added later by a Frenchman named Antoine Galland) fit the mold perfectly. They show us that the human desire for "wonder" and "poetic justice" is universal.

The Modern Fairy Tale: Is It Still Happening?

Some people argue that superhero movies are our modern fairy tales. I disagree. Superheroes are more like the Greek Myths; they represent demi-gods with specific powers and massive backstories.

True modern fairy tales are found in "magical realism" or urban fantasy. Think of Neil Gaiman’s Stardust or Coraline. These stories take the old rules—don't eat the food in the other world, be kind to the old woman on the road—and drop them into a context we recognize.

What a fairy tale does better than any other genre is balance the mundane with the impossible. You’re just a guy looking for a job, and then a cat in boots tells you he can make you a Marquis. And for some reason, you believe him.

How to Spot a "Fake" Fairy Tale

Not every story with a dragon is a fairy tale.

High fantasy (like Lord of the Rings) isn't a fairy tale because it spends 500 pages explaining the political history of Middle-earth. Fairy tales don't care about politics. They care about the moment of magic. If the story spends too much time on "world-building," it’s probably fantasy. If the magic is unexplained, sudden, and serves a moral or symbolic purpose, you’re in fairy tale territory.

Also, watch out for the "Literary Fairy Tale." These are stories written by a single author meant to imitate folk tradition. Hans Christian Andersen is the king of this. The Little Mermaid and The Ugly Duckling aren't folk tales passed down through generations; he made them up. You can tell because they are way more melancholic and focused on individual suffering than the older, punchier oral tales.

📖 Related: Cute Reusable Grocery Bags: Why Your Aesthetic Tote Might Be Failing The Planet

Actionable Ways to Explore Fairy Tales Today

If you want to move beyond the cartoon versions and really understand the depth of this genre, stop watching the movies for a second. Try these instead:

- Read the Uncut Versions: Pick up the Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (the Jack Zipes translation is the gold standard for accuracy). It will change how you view "classic" characters.

- Listen to Oral Traditions: Look for recordings of Appalachian Jack Tales. These are Americanized versions of European fairy tales that survived in the mountains, featuring a hero named Jack who outsmarts giants with his wits rather than magic.

- Check the ATU Index: If you’re a writer or a nerd, look up a story’s ATU number. Seeing how Beauty and the Beast (Type 425C) relates to The Small-Tooth Dog or The Enchanted Pig is a trip.

- Visit the Sources: Read Giambattista Basile’s The Tale of Tales (Pentamerone). It’s 17th-century Italian, it’s vulgar, it’s hilarious, and it’s where many of our modern tropes actually began.

Fairy tales are the "bones" of our storytelling culture. They aren't meant to be pretty; they’re meant to be sturdy. They remind us that the world is dangerous, that kindness is a currency, and that even the smallest person can find a way to outsmart a giant.

Next time you see a "Once upon a time," look past the glitter. Look for the teeth. They've been there all along.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge:

- Compare a Perrault version of a story (like Cinderella) with the Grimm version to see how French "courtly" culture differed from German "folk" culture.

- Explore the works of Angela Carter, specifically The Bloody Chamber, to see how modern authors deconstruct fairy tale tropes for adult audiences.

- Research the "Fitcher's Bird" story if you want to see just how terrifying the Grimm tales could get before they were edited for children.