Most people think Labor Day is just the "unofficial end of summer." It’s the Monday where you grill some burgers, check out the mattress sales, and realize with a bit of dread that school starts tomorrow. But honestly, if you ask the average person what does Labor Day stand for, they’ll probably mention something vague about "the workers" before heading back to the cooler.

It's way grittier than a backyard BBQ.

The holiday is actually a somber, hard-won victory born out of a time when the "American Dream" felt more like a nightmare for the people actually building the country. We're talking 12-hour shifts. Seven days a week. Kids as young as five or six years old working in coal mines and textile mills. Labor Day wasn't "given" to us by generous corporations; it was demanded through strikes, protests, and, in some cases, literal blood.

The Violent Origins of Your Three-Day Weekend

To understand what does Labor Day stand for, you have to look at the late 1800s. The Industrial Revolution was screaming at full throttle. While the titans of industry were getting unimaginably rich, the people on the floor were dying. Literally.

There were no safety regulations. No "human resources" department to complain to. If you got your hand crushed in a machine, you were fired before the ambulance—which didn't exist anyway—could have arrived.

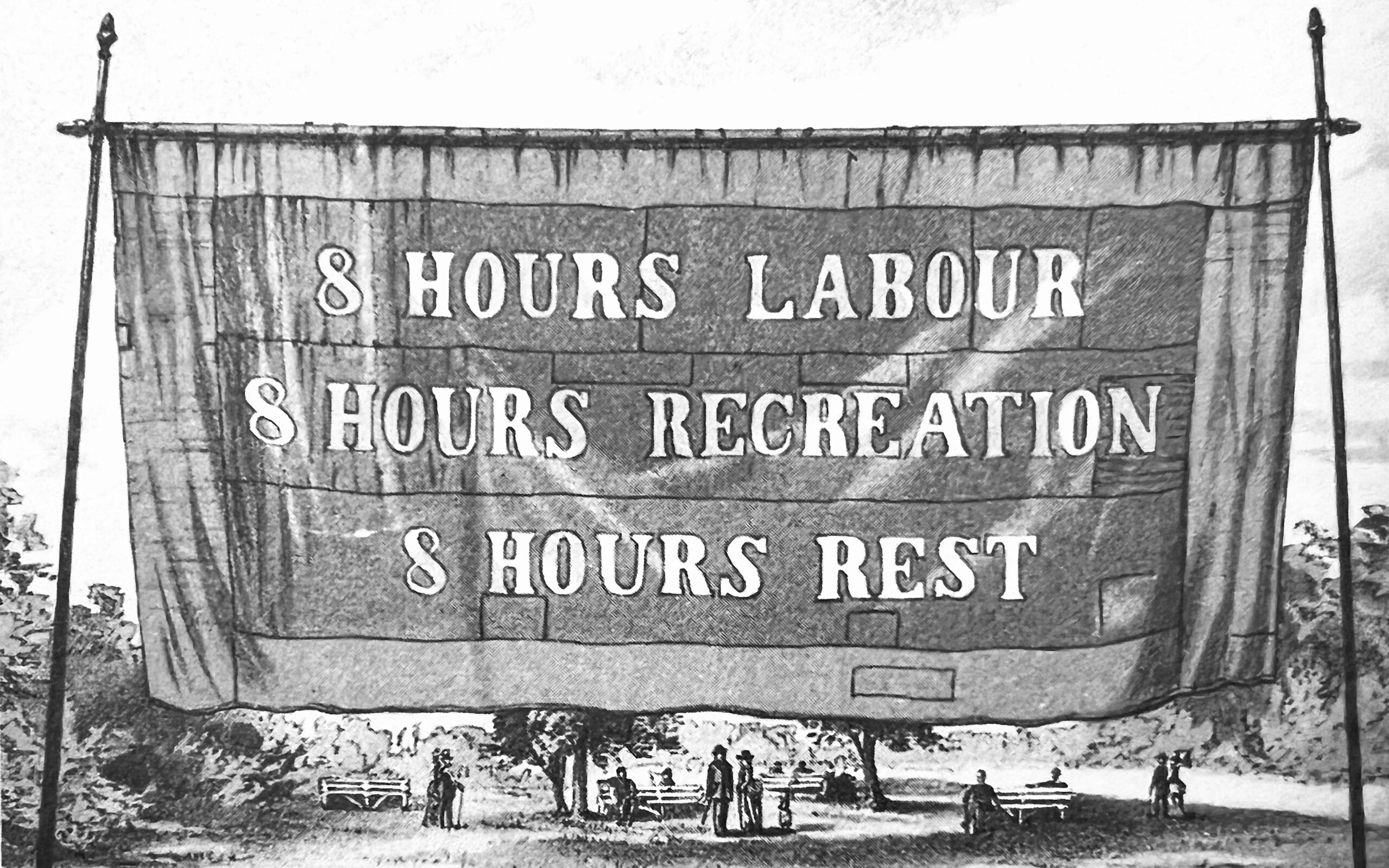

The very first Labor Day parade happened on September 5, 1882, in New York City. It wasn't a government-sanctioned event. About 10,000 workers took unpaid time off—risking their jobs—to march from City Hall to Wendel’s Elm Park. They wanted to show the public the "strength and esprit de corps of the trade and labor organizations." They wanted an eight-hour workday. They wanted a voice.

It was basically a giant, coordinated "sick day" that forced the city to pay attention.

McGuire vs. Maguire: The Great Typo Debate

History is funny because we can't even agree on who started the thing. For decades, Peter J. McGuire, a co-founder of the American Federation of Labor, got all the credit. But recently, many historians have started pointing toward Matthew Maguire, a machinist from Paterson, New Jersey.

👉 See also: Scary Halloween Makeup Ideas That Actually Work (And How to Not Mess Them Up)

The theory? Maguire was a bit too "radical" for the tastes of the time, so the more moderate McGuire was credited to make the holiday more palatable to the middle class. Regardless of which "M" name actually penned the proposal, the intent remained: a day for the people who make the world turn.

Why the Government Finally Caved

You might wonder why Congress suddenly decided to make this a federal holiday in 1894. It wasn't out of the goodness of their hearts. It was a PR move to stop a revolution.

The Pullman Strike of 1894 was the turning point. Workers for the Pullman Palace Car Company went on strike because George Pullman cut their wages but refused to lower the rent in the company town where they lived. It paralyzed the national railroad system. President Grover Cleveland sent in federal troops to break the strike, which led to a series of riots and deaths.

Cleveland was in hot water. To appease the angry labor movement and try to win back some votes, he rushed the Labor Day Act through Congress. It was signed into law just six days after the strike ended. It was a peace offering, a way for the government to say, "We hear you," even while the smoke from the riots was still clearing.

What Does Labor Day Stand For in 2026?

Today, the meaning has shifted, but the core remains relevant. We live in a world of "hustle culture" and the "gig economy." Sometimes it feels like we’ve circled back to 1882. We check emails at 11:00 PM. We work three different apps just to pay rent.

So, what does Labor Day stand for now?

It stands for the radical idea that your life is worth more than your productivity.

It’s a celebration of the 40-hour workweek (which is disappearing), the weekend (which many people still don't get), and the safety standards we often take for granted. It’s a moment to acknowledge that without the person driving the truck, the person stocking the shelf, and the person coding the software, the entire machine grinds to a halt.

The Fashion "Rule" That Everyone Ignores

We’ve all heard it: "Don't wear white after Labor Day."

🔗 Read more: Why Hot Nude Tattoo Women Are Actually Redefining Contemporary Art

This has absolutely nothing to do with labor rights. It was a snobbish social separator in the early 1900s. Wealthy women who could afford to leave the city for the summer wore white to stay cool. When they returned to the city in September, they put away their "vacation clothes" and put on their "city clothes" (usually darker fabrics). It became a way for old-money elites to identify who belonged and who didn't.

If you want to wear white in mid-September, go for it. The Labor Day founders were fighting for your right to a living wage, not your wardrobe choices.

The Global Difference: May Day vs. Labor Day

If you travel almost anywhere else in the world, "Labor Day" is on May 1st. International Workers' Day commemorates the Haymarket Affair in Chicago, which was a much more violent struggle for the eight-hour day.

Why is the US different?

Simple: Politics. President Cleveland and other leaders specifically chose the September date to distance the American holiday from the socialist and anarchist associations of May 1st. They wanted a holiday that felt like a parade, not a riot. We got the "tamer" version of the holiday, which is why it eventually morphed into a day for shopping and beach trips rather than political rallies.

Why the "Labor" in Labor Day is Changing

The nature of work is unrecognizable compared to 1894. We aren't all standing in front of looms or forging steel. But the struggles are just as real.

👉 See also: Nike Dunk Low Pandas: Why Everyone Still Wants the Shoe They Hate

- Mental Health: Labor rights now include the "right to disconnect."

- Automation: As AI takes over tasks, the holiday reminds us that humans still need a way to support themselves.

- The Gender Gap: Equal pay for equal work is the modern-day equivalent of the 19th-century fight against child labor.

When you think about what does Labor Day stand for, think about the fact that you aren't a cog. You’re a person with a life outside of your "output."

Actionable Ways to Honor the Day (Beyond Grilling)

If you actually want to respect the history of the holiday this year, don't just sleep in.

- Tip heavily. If you go out to eat or order delivery on Labor Day, remember that those workers are missing their holiday so you can enjoy yours. A 25% or 30% tip is a direct way to honor the spirit of the day.

- Support a local business. Skip the massive "Big Box" sales. The owners of local shops are usually the ones working the hardest to keep their communities afloat.

- Read up on your rights. Do you actually know what your state's labor laws are regarding overtime, breaks, or wrongful termination? Knowledge is the ultimate protection.

- Actually stop working. Seriously. Close the laptop. Turn off the notifications. The biggest way to honor the people who fought for the "weekend" is to actually use it for its intended purpose: rest.

Labor Day is the only holiday dedicated to the "common man" and woman. It’s not about a war, a religious figure, or a president. It’s about you. It’s about the fact that your sweat and your time have value. So, enjoy the burger, but remember that the reason you’re holding it is because a century ago, people marched so you wouldn't have to spend your entire life at a desk or a machine.

That is what Labor Day really stands for. It's a reminder that we work to live, we don't live to work. Keep that in mind when the alarm goes off on Tuesday morning.

Next Steps for Your Holiday Weekend:

Check your local municipal calendar for any remaining traditional Labor Day parades; many cities like New York and Chicago still host massive events that stay true to the 1882 roots. Alternatively, look up the "Department of Labor" website for your specific state to see what new worker protection laws took effect in 2026—staying informed is the best way to protect the legacy of those who marched before us.