You want it all. Everyone does. But the universe—and your bank account—usually has other plans. If you've ever stood in a grocery aisle staring at a name-brand box of cereal and a generic one, wondering if the extra two dollars is worth the "premium" crunch, you’ve hit the core of the issue. So, what does trade off mean in a way that actually matters for your life?

Basically, it’s the price of "yes."

Whenever you choose one thing, you’re killing off another option. It’s brutal. Economists call this "opportunity cost," which is just a fancy way of saying you can’t be in two places at once. If you spend $1,000 on a new iPhone, that’s $1,000 you aren’t putting into an index fund or using for a weekend trip to Vegas. You didn't just buy a phone; you traded a vacation for a screen. That’s the reality of a trade off.

The Brutal Logic of Scarcity

Scarcity is the root of the problem. We have finite time, finite money, and finite energy. Our desires? Those are infinite. Thomas Sowell, a well-known economist, famously said there are no solutions, only trade-offs. It’s a bit of a cynical take, but he’s right. If a city decides to build a new park, they might have to skip repaving three miles of road. You can't have the smooth road and the playground without raising taxes, which—you guessed it—is another trade off.

Think about sleep.

You stay up late watching a documentary on Netflix because it’s fascinating. You’re gaining knowledge and entertainment. But you're trading away alertness the next morning. You’re trading your 9:00 AM productivity for a 1:00 AM dopamine hit. Most of us make these deals unconsciously. We drift through the day making dozens of micro-trades without realizing we’re actually managing a complex personal economy.

Why We Struggle With the Math

Our brains aren't naturally wired to enjoy the idea of losing out. We suffer from something called loss aversion. Psychologically, the pain of losing $50 is about twice as potent as the joy of gaining $50. This makes acknowledging a trade off feel like a defeat. We want the "win-win" scenario. Marketing teams know this. They try to convince you that you can have "luxury at an affordable price" or "high performance with zero maintenance."

Honestly? They’re usually lying.

There is almost always a catch. High performance usually requires expensive parts or more frequent tune-ups. Affordable luxury usually means they cut corners on the materials you can’t see, like the frame of a sofa or the stitching inside a shoe. Understanding what does trade off mean requires a level of cynicism that protects your wallet. You have to ask: "What am I giving up that isn't being mentioned?"

Real World Examples: Business and Tech

In the world of software development, there’s a concept called the Project Management Triangle. It’s a classic. You have three points: Fast, Good, and Cheap. The rule is you can only pick two.

- If you want it fast and good, it’s going to be expensive.

- If you want it cheap and fast, it’s probably going to be garbage.

- If you want it good and cheap, it’s going to take forever.

Companies like Apple often choose "Good" and "Fast" (at least in terms of product cycles), which is why their hardware costs a premium. On the flip side, companies like Walmart focus on "Cheap." The trade off there is often the shopping experience or the long-term durability of the goods.

👉 See also: Planet Fitness DEI Policy: What’s Actually Happening Behind the Scenes

Consider the transition to electric vehicles (EVs). Governments and consumers are currently navigating a massive trade off. EVs offer lower tailpipe emissions and potentially lower fuel costs over time. But the trade off includes higher upfront purchase prices, the environmental impact of lithium mining, and the "time cost" of charging compared to a five-minute gas station stop. You aren't just switching cars; you're switching which set of problems you’re willing to live with.

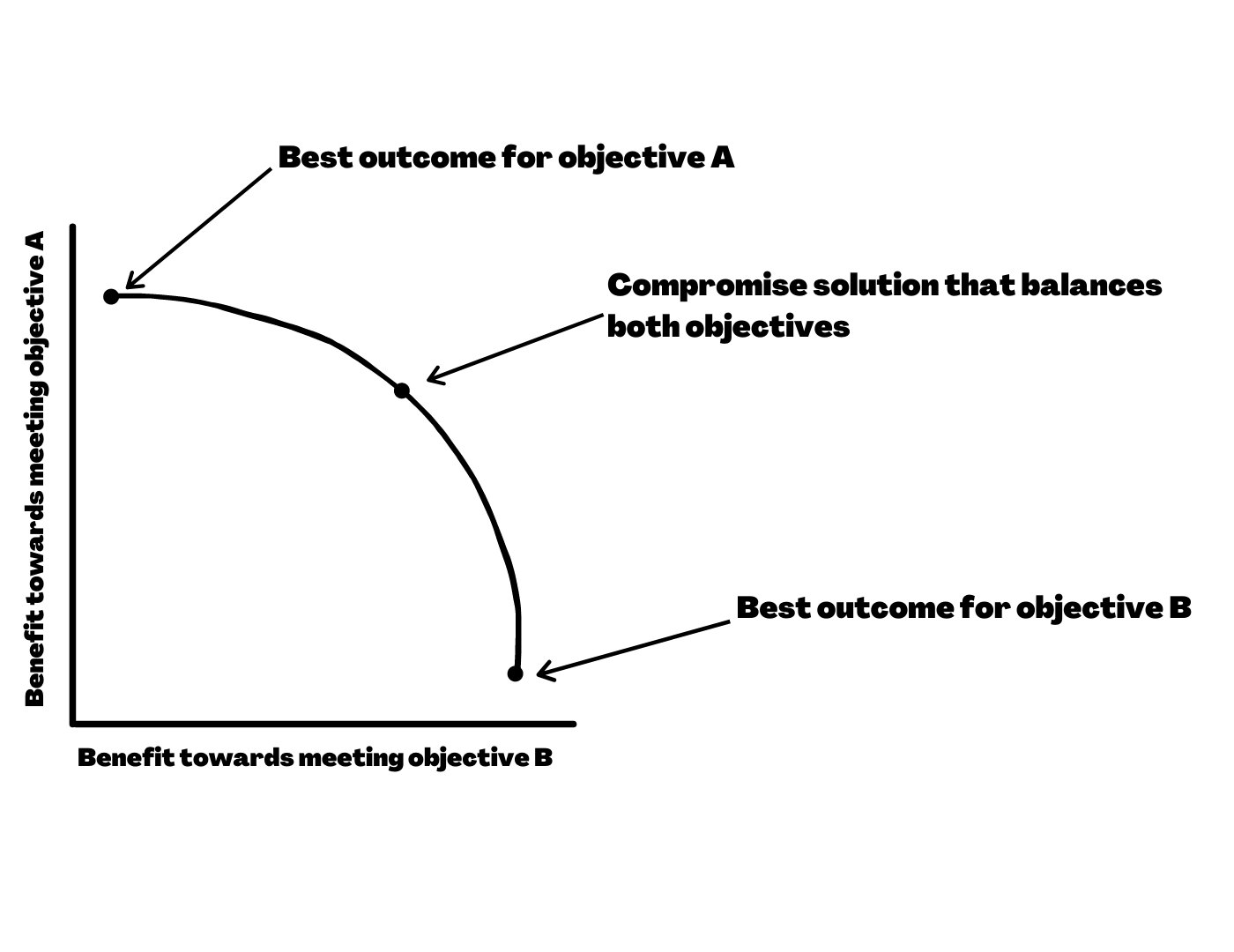

The Nuance of the "Middle Ground"

Sometimes people try to find a middle ground to avoid the trade off. This is often where "mediocrity" is born. If a restaurant tries to serve Italian, Mexican, and Chinese food all at once, they usually end up being mediocre at all of them. By refusing to trade off variety for specialization, they lose the "quality" edge. Expert-level performance usually requires an extreme trade off. Olympic athletes trade a "normal" social life and diverse hobbies for thousands of hours of repetitive, grueling practice. You can't be a world-class sprinter and a world-class pastry chef simultaneously. There just aren't enough hours in the day.

How to Calculate the "Hidden" Costs

To really get what a trade off is, you have to look at the secondary effects. This is where most people trip up.

Let's say you take a higher-paying job. It's an extra $30,000 a year. On paper, it looks like a straight win. But the new job requires a 90-minute commute instead of 20 minutes. That’s an extra 140 minutes a day in the car. Over a year, that’s about 580 hours. If you divide that $30,000 by the 580 hours you're spending in traffic, you’re basically getting paid about $50 an hour to sit in your car and stress out. Is that worth it? For some, yes. For others, that’s a terrible trade.

Then there’s the "sunk cost" trap. People stay in bad relationships or failing businesses because they've already "invested" so much. They think that by leaving, they’re wasting that investment. In reality, by staying, they are trading away their future happiness to justify a past mistake. The trade off should always be calculated based on what you do next, not what you did yesterday.

The Role of Risk

Risk is the silent partner in every trade off. When you invest in a "safe" savings account, you’re trading the potential for high returns (like in the stock market) for the certainty that your money won't disappear. You are trading growth for sleep-at-night security.

Conversely, a venture capitalist trades security for the slim chance of a 100x return. They know most of their bets will fail. They’ve accepted that loss as part of the trade.

Actionable Steps for Better Decision Making

Stop trying to avoid trade-offs. Start choosing them intentionally. If you don't choose your trade-offs, life will choose them for you, and you probably won't like the result.

1. Define your "Non-Negotiables" first.

Before you look at options, decide what you aren't willing to give up. If your health is a non-negotiable, you cannot trade away your sleep or gym time for a work project, no matter how much it pays. This simplifies the math instantly.

2. Use the "10-10-10 Rule."

When facing a tough trade off, ask how you’ll feel about the decision in 10 minutes, 10 months, and 10 years. Buying that expensive gadget feels great in 10 minutes. In 10 months, the novelty has worn off. In 10 years, you might regret not having that money in your retirement fund.

3. Map the "Second-Order Effects."

Ask yourself: "And then what?" If you buy a bigger house, you have more space. And then what? You have higher utility bills. And then what? You have less disposable income for travel. And then what? You might feel trapped in your job because you need the high salary to pay the mortgage.

4. Audit your time like you audit your taxes.

Spend a week tracking where every hour goes. You’ll quickly see what you’re trading your life for. If you spend 15 hours a week scrolling social media, you are trading roughly two full workdays a month for digital noise. Is that a trade you’d consciously make if someone asked you to sign a contract for it?

5. Accept the "Good Enough."

In psychology, there are "maximizers" and "satisficers." Maximizers try to find the absolute best option in every trade off. They usually end up miserable and exhausted. Satisficers find an option that meets their criteria and then stop looking. They trade the "perfect" choice for "peace of mind." Be a satisficer whenever the stakes are low.

Every choice is a sacrifice. Once you lean into that, the pressure to "have it all" disappears. You realize that saying "no" to a good opportunity is often the only way to say "yes" to a great one. That is the ultimate mastery of the trade off.