You’ve seen the photos. A five-year-old in a tiny flight suit sitting in a cockpit, or a teenager laughing next to a Marvel actor on a movie set. They’re wearing that familiar blue T-shirt with the white star logo. Everyone knows the name, but if you ask the average person what is a Make a Wish kid, they usually get the most important part wrong.

Most people think these kids are terminally ill. They think a "wish" is a final goodbye.

That is a huge misconception. In fact, it’s arguably the biggest myth in the non-profit world. A Make-A-Wish kid is a child between the ages of 2½ and 18 who has been diagnosed with a critical illness—not necessarily a terminal one. Roughly 70% of these kids actually survive their illnesses and go on to lead healthy adult lives. The wish isn’t a "last hurrah." It’s a medical intervention disguised as a party.

The Actual Definition of a Make-A-Wish Kid

To understand the reality, you have to look at the medical criteria. A child becomes a Make-A-Wish kid when a doctor certifies that they are battling a condition that is "life-threatening." This includes things like advanced-stage cancer, certain heart conditions, cystic fibrosis, or rare genetic disorders.

It’s about the fight.

The organization was founded back in 1980, inspired by a little boy named Chris Greicius who wanted to be a police officer. He had leukemia. His community in Arizona pulled together to give him a uniform, a badge, and a helicopter ride. He passed away shortly after, but he left behind a blueprint for how to handle the crushing weight of childhood sickness. Today, a child is referred to the foundation every 20 minutes in the United States.

Referrals can come from the kids themselves, their parents, or—most commonly—their medical team. Once the medical eligibility is confirmed, the "wish journey" starts. It isn’t just a one-day event. It’s months of planning, anticipation, and hope that serves as a literal distraction from chemotherapy, surgeries, and hospital walls.

Why Doctors Treat Wishes Like Medicine

It sounds "soft," right? A trip to Disney or meeting a celebrity doesn't cure Stage IV neuroblastoma. But if you talk to pediatric oncologists, they’ll tell you something different.

Dr. Shaina S. Willen and other researchers have looked into the "Wish Effect." There’s a psychological shift that happens. When a kid is stuck in a cycle of "no"—no, you can't go to school; no, you can't eat that; no, this is going to hurt—the wish is the first "yes" they’ve heard in months.

It changes their physiological response to treatment.

Studies have shown that kids who receive wishes are often more compliant with their medical protocols. They’re more likely to take the pills that taste like copper or endure the radiation because there is something massive on the horizon. It’s a goal. It’s a reason to keep pushing. One study published in Wellness Management even suggested that wish fulfillment can lead to fewer unplanned hospitalizations and emergency room visits.

Basically, hope is a clinical necessity.

The Four Categories of a Wish

Not every kid wants to go to Florida. While "I want to go" (usually to a theme park) makes up a huge chunk of the requests, the foundation breaks wishes down into four specific buckets.

- I want to go: This is the classic. Disney World, Hawaii, the Grand Canyon, or even just a specific beach they saw in a book.

- I want to be: This is where the "Batkid" stories come from. A kid wants to be a firefighter, a model, a chef, or a forest ranger for a day.

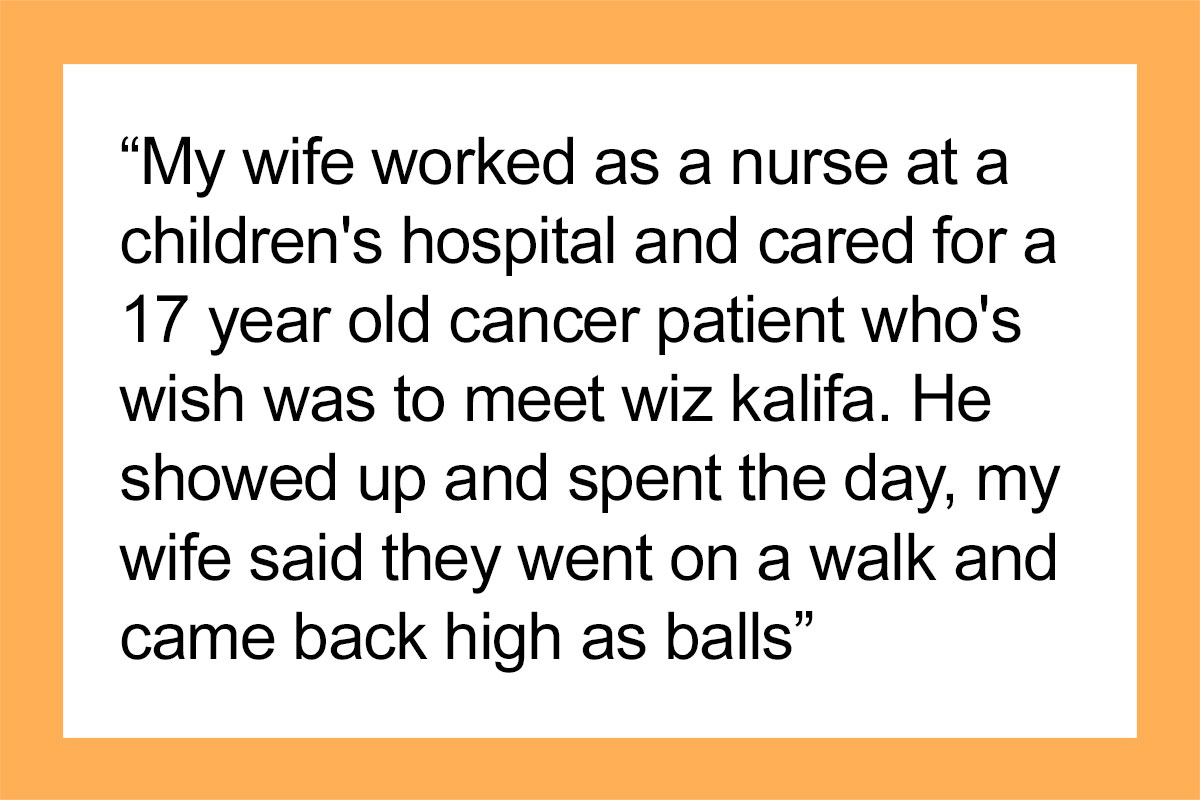

- I want to meet: Celebrities, athletes, or even the Pope. John Cena famously holds the record for the most wishes granted—over 650. He’s basically a saint in the eyes of the foundation.

- I want to have: Sometimes kids just want a "thing." A gaming computer, a backyard treehouse, a puppy, or a sensory room for a child with complex neurological needs.

- I want to give: This is the rarest but most heart-wrenching. Some kids use their wish to build a playground for their school or buy equipment for the hospital ward where they spent their time.

Life After the Wish

We need to talk about what happens when the trip ends.

Because many of these kids recover, the "Make-A-Wish kid" identity eventually shifts into "Make-A-Wish alum." These are adults who grew up to be doctors, teachers, and parents because they beat the odds. They often cite their wish as the turning point in their mental health during treatment.

It’s not all sunshine, though. There is a "post-wish blues" that some families experience. Coming home from a week of being treated like royalty to the reality of medical bills and pharmacy runs is a hard pill to swallow. That’s why the community aspect—the local chapters—stays involved. They don't just drop a kid off at the airport and disappear.

💡 You might also like: Why the Low Picnic Table for Sitting on the Floor is Making a Massive Comeback

Addressing the "Rich vs. Poor" Debate

A common question that pops up is whether the family’s income matters. Honestly, it doesn't.

A Make-A-Wish kid can come from a billionaire family or a family living below the poverty line. The illness is the equalizer. The foundation covers everything—flights, spending money, insurance, limo rides—regardless of the family's bank account. This is because the trauma of a sick child affects every family, and the goal is to remove the "logistics" of joy so the parents can just be parents for a second, instead of being nurses.

How the Process Actually Works

It’s surprisingly rigorous.

First, the referral. Anyone with firsthand knowledge of the child can initiate this.

Second, the medical discovery. The foundation’s medical professionals contact the child’s treating physician to see if the condition meets the "life-threatening" criteria.

Third, the wish granters. Two volunteers (wish granters) meet with the child. They don't ask "What do you want?" right away. They ask about the child's imagination. They want to find the "heart of the wish." If a kid says "I want to go to Disney," the granters dig deeper. Do they love the rides? Or do they just want to see Mickey? Sometimes the "real" wish is something much more specific.

Fourth, the design. This is the logistics phase.

Fifth, the fulfillment. The magic happens.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Funding

You might think the government pays for this. They don't.

Make-A-Wish is almost entirely funded by individual donors and corporate sponsors. They don't take federal grants. This means the number of kids who get to be "Make-A-Wish kids" is directly tied to how much money is raised each year. In 2023, they granted over 15,000 wishes in the US alone, but there are still thousands of kids waiting.

Wait times can be a few months to over a year, depending on the complexity of the wish and the child's health status. Emergency wishes (when a child's health is rapidly declining) are fast-tracked, sometimes happening in as little as 24 to 48 hours.

Actionable Ways to Support a Make-A-Wish Kid

If you’re reading this and want to do more than just understand the definition, there are three distinct paths you can take that actually move the needle.

Frequent Flier Miles

This is the "secret" way to help. About 70% of wishes involve air travel. You can donate your expiring or unused miles (Delta, United, American, etc.) to the foundation. They never expire once donated, and it’s a way to provide a $500–$2,000 value without spending a dime out of your pocket.

Volunteer as a Wish Granter

If you have a knack for planning and empathy, local chapters are always looking for people to be the "boots on the ground." You’ll be the person who interviews the kids and helps design the experience. It requires a background check and some training, but it’s the most direct way to see the impact.

Refer a Child

If you know a family struggling with a serious illness, don't assume someone else has already referred them. Many parents are too overwhelmed with hospital visits to even think about it. You can start the inquiry on the Make-A-Wish website. Even if the child isn't eligible, the foundation can often point the family toward other resources.

Being a Make-A-Wish kid isn't about being a victim of a disease. It's about being a person whose imagination is bigger than their diagnosis. It's a badge of honor for kids who are fighting battles most adults couldn't handle.

Next time you see a kid in that blue shirt, don't feel sorry for them. They’re in the middle of a story that’s moving toward hope, not an ending.