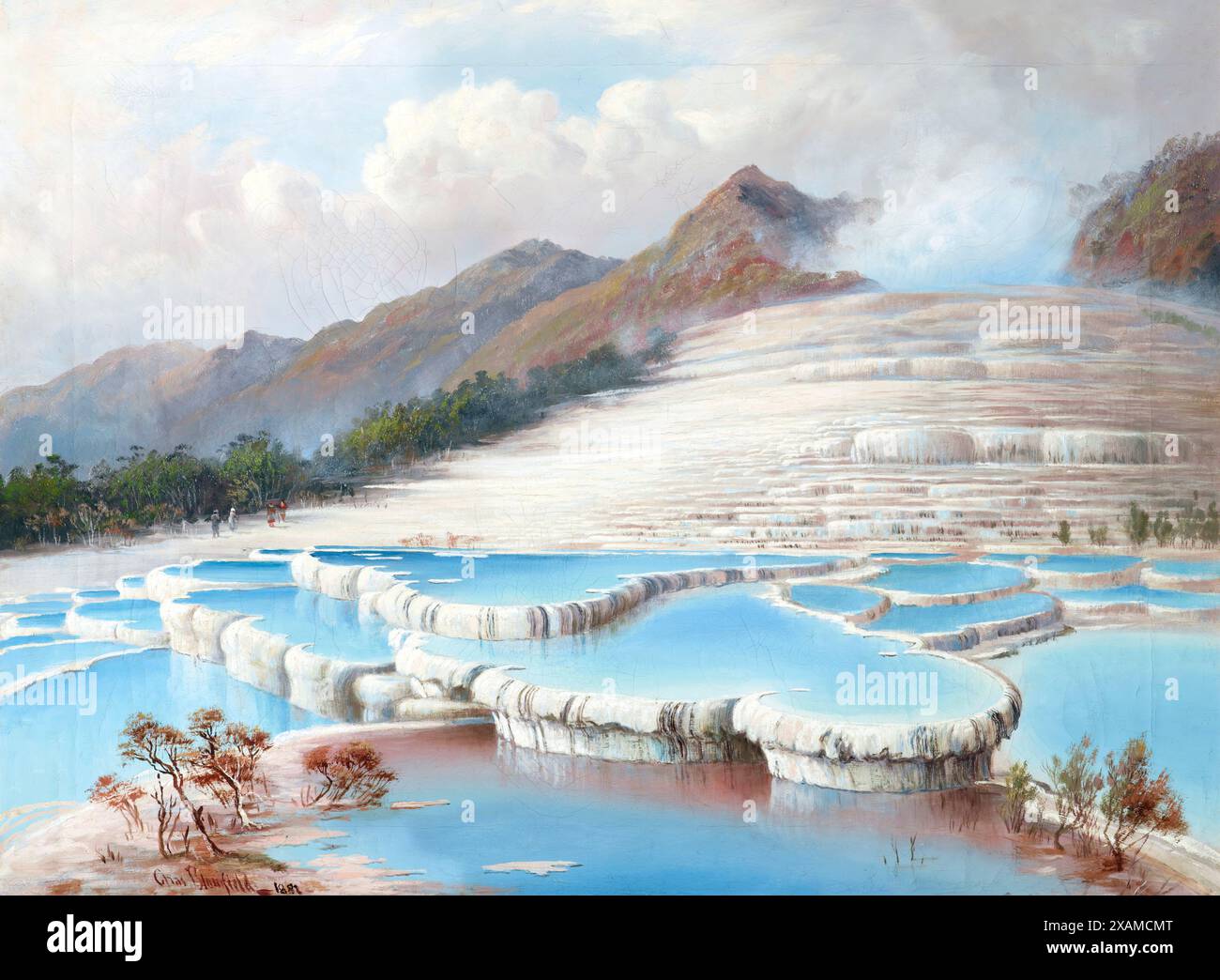

New Zealand used to have something that people called the eighth wonder of the world. It wasn’t a mountain or a forest, though the country has plenty of those. It was a pair of geothermal steps—the Pink and White Terraces—that cascaded down into the waters of Lake Rotomahana. They were massive. The White Terraces, or Te Tarata (the tattooed rock), covered about eight hectares. The Pink Terraces, Otukapuarangi (fountain of the clouded sky), were smaller but arguably more beautiful with their soft, salmon-hued silica.

Then, in the middle of the night in June 1886, they just... vanished.

Mount Tarawera decided to blow its top. It wasn't just a small puff of smoke; it was a violent, basaltic eruption that ripped a 17-kilometer rift across the mountain and the lake floor. For over a century, the world assumed these natural marvels were pulverized. Gone forever. But lately, the story has gotten weird. Researchers are arguing. Modern sonar is seeing things. There is a very real possibility that parts of the Pink and White Terraces are still down there, buried under meters of mud and ash, waiting for someone to find them.

The Victorian Version of Instagram

Back in the 1870s, getting to the Pink and White Terraces was a nightmare. You had to take a ship to Auckland, a horse to the Rotorua district, and then a whaleboat across the lake. It was expensive. It was grueling. Yet, people did it. Global travelers flocked to the site because the visuals were unlike anything else on Earth.

The White Terrace looked like a giant staircase of frozen marble. Boiling water from a geyser at the top flowed down, cooling and leaving behind thick layers of white silica. As the water pooled in the basins, it turned a deep, bright turquoise. On the other side of the lake, the Pink Terrace was where people actually bathed. The water was lukewarm by the time it reached the bottom tiers, making it the world’s first luxury destination spa.

👉 See also: Getting Lost? The Map of Majorca Island Explained Like a Local

Artists like Charles Blomfield spent years painting them. Honestly, thank God he did. His paintings are some of the only high-fidelity records we have of what the terraces actually looked like before the mountain exploded. He was actually there when it happened—well, not on the mountain, but he was in the region and saw the devastation. He went back later and found nothing but a steaming crater where the beauty used to be.

The Night the Mountain Ripped Open

June 10, 1886. 2:00 AM. The ground started shaking.

It wasn’t just an earthquake; it was the start of a six-hour eruption that would change New Zealand’s geography permanently. The eruption at Mount Tarawera was unique because it occurred along a linear fissure. When that fissure hit Lake Rotomahana, the water flashed into steam instantly. This is what geologists call a phreatomagmatic eruption. It’s incredibly destructive.

The lake basically exploded.

A mixture of mud, ash, and pulverized rock—known as the Rotomahana Mud—was ejected into the sky and rained down on the surrounding villages. Te Wairoa was buried. More than 120 people lost their lives. When the sun finally tried to come up, it couldn't. The ash cloud was so thick it stayed dark as night for hours. When the dust finally settled, Lake Rotomahana was gone, replaced by a massive, steaming chasm that was several times larger and deeper than the original lake.

Within a few years, the chasm filled with water again, creating the much larger Lake Rotomahana we see today. The Pink and White Terraces were nowhere to be found.

The Scientific Dogfight: Are They Actually Gone?

For a long time, the case was closed. The terraces were gone. End of story.

But in 2011, a joint project between GNS Science and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution used autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) to map the lake floor. They found something. Using side-scan sonar, they spotted what looked like the crescent-shaped edges of terrace tiers. Specifically, they claimed to have found portions of the Pink Terraces at a depth of about 60 meters.

Then, things got spicy in the scientific community.

💡 You might also like: Cape Coral Red White and Boom: What Most People Get Wrong About Florida’s Biggest One-Day Event

Rex Bunn and Dr. Sascha Nolden published research suggesting everyone was looking in the wrong place. They didn’t use sonar; they used the 1859 diaries of Ferdinand von Hochstetter. Hochstetter was a German-Austrian geologist who had done the only high-quality survey of the lake before the eruption. By using his field notes and "re-sectioning" his survey points, Bunn and Nolden argued that the terraces weren't at the bottom of the current lake at all.

Instead, they believe the Pink and White Terraces are buried on land, under the shore of the modern lake.

Basically, because the lake changed shape so much during the eruption, the old shoreline is now inland. If they are right, the terraces might be perfectly preserved under layers of volcanic ash, much like Pompeii. It’s a bold claim. It has led to a lot of back-and-forth in the Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. Some scientists think the 2011 sonar data is definitive; others think the Hochstetter survey is the "Rosetta Stone" that proves they are on dry land.

Why We Can't Just Start Digging

You might wonder why we don't just grab a few excavators and find out. It’s not that simple. The area is tapu (sacred) to the local iwi, Tuhourangi. This is their ancestral land. It’s also the site of a massive tragedy where their ancestors were buried alive. Any archaeological work requires immense cultural sensitivity and permission.

There's also the geological reality. The ground around Rotomahana is still very much active. It’s hot. There are fumaroles, boiling mud pools, and unstable ground everywhere. It’s not exactly a "safe" construction zone.

But the mystery is what keeps the legend alive. If the Pink and White Terraces are intact, they represent a geological time capsule. We’d be able to see exactly how silica sinters form over thousands of years. We’d see the world as it was in 1886.

What You See If You Visit Today

If you go to the Rotorua region now, you can’t see the terraces, but you can feel the ghost of them. The Waimangu Volcanic Valley is the direct result of that 1886 eruption. It is the world’s youngest geothermal system.

It's surreal.

You can walk past Frying Pan Lake—which is one of the largest hot springs in the world—and see the steaming cliffs of the Inferno Crater. The water there is a vivid, milky blue that looks exactly like the descriptions of the old terrace pools. It gives you a sense of the scale. The power required to move that much earth and water is hard to wrap your head around until you’re standing in the middle of the valley.

📖 Related: Best Tango Shows in Buenos Aires: What Most People Get Wrong

The Buried Village of Te Wairoa is another must-see if you're trying to understand this. You can walk through the excavated ruins of the hotel and the whare (houses) that were hit by the mudfall. They have recovered items like bread marmalade jars and leather boots, all frozen in time by the ash. It makes the "eighth wonder of the world" feel less like a myth and more like a real place where people lived, worked, and eventually fled for their lives.

How to Explore the History Yourself

If you’re interested in the Pink and White Terraces, don't just look at a grainy photo on Wikipedia. You have to look at the intersection of history and modern tech.

First, look up the Blomfield paintings. He captured the light hitting the silica in a way that photos from that era simply couldn't. Then, check out the GNS Science bathymetric maps of Lake Rotomahana. Seeing the 3D rendering of the lake floor next to the old sketches is wild. You can actually see where the old shoreline used to be.

The debate between the "submerged" theory and the "buried on land" theory isn't settled. New papers are still being published. Some researchers are currently looking into using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to scan the land sites identified by Bunn and Nolden. If they find a massive silica structure under the dirt, it will be the biggest archaeological find in New Zealand history.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

- Visit Waimangu Volcanic Valley: This is the closest you will get to the "vibe" of the terraces. It’s the direct descendant of the eruption.

- Check out the Rotorua Museum (Te Whare Taonga o Te Arawa): While the main building has faced its own seismic challenges recently, their digital archives and satellite exhibitions are the best place to see the actual artifacts recovered from the era.

- Read the Hochstetter Diaries: If you're a map nerd, Sascha Nolden’s work translating and publishing Ferdinand von Hochstetter’s notes is fascinating. It’s the closest thing we have to a treasure map.

- Support Local Iwi-led Tourism: When visiting Tarawera or Rotomahana, go with guides from the Tuhourangi tribal authority. They provide the cultural context that a textbook simply can't offer.

The Pink and White Terraces might be gone, or they might just be hiding. Either way, the story of their destruction and the hunt to find them again is a reminder that the earth under our feet is anything but permanent. It shifts, it explodes, and sometimes, it swallows wonders whole.