You’ve probably heard the old joke: "How did the guy who invented the clock know what time it was?" It sounds like a stoner thought or a riddle from a five-year-old. But honestly, it’s a brilliant question. If you’re building the very first device to track hours, minutes, and seconds, you can't just check your iPhone to sync the gears. You have nothing to reference.

So, what time was it when they invented the clock?

The short, somewhat annoying answer is that they didn’t "invent" the clock at a specific moment. There was no "Hour Zero." Humans have been obsessively tracking the sun’s movement for millennia. By the time the first mechanical clocks started ticking in European monasteries around the 1300s, we already had a very firm, if slightly messy, grasp on the time. They didn't invent the time; they just automated the way we watched it.

The High Noon Problem

Before gears and springs, we had the sun. That was the master clock. For thousands of years, "noon" was simply when the sun hit its highest point in the sky. It was undeniable. You look up, the shadow is at its shortest, and that’s noon. Period.

Early clockmakers used sundials to "set" their mechanical inventions. If you were building a verge-and-foliot clock in a 14th-century bell tower, you waited until the sun hit the noon mark on a local sundial, and then you kicked the heavy stone weights into motion. You basically told the machine, "This is twelve," and hoped the friction in the iron gears didn't slow it down too much by tomorrow.

It’s kinda wild to think about, but every town had its own time. If you walked twenty miles east, your watch—if you had one—would be "wrong" because the sun hits its peak earlier the further east you go. This didn't matter when the fastest thing on earth was a horse. People lived in "local apparent time."

Monks, Bells, and the Need for Precision

Why did we even bother with mechanical clocks? Why not stick to the sun?

Because the sun is unreliable. It hides behind clouds. It disappears for twelve hours a day. And for medieval monks, this was a massive spiritual problem. The Catholic Church operated on "canonical hours." These were specific times for prayer, like Matins (mid-night) and Lauds (early morning). If you were a monk in 1250, you couldn't afford to oversleep and miss praising the Creator just because it was a cloudy Tuesday.

They needed a way to measure time when the sun wasn't looking.

Before the mechanical revolution, they used water clocks (clepsydrae). Imagine a giant bowl with a tiny hole. As water dripped out, marks on the side showed the passing hours. But water freezes. It evaporates. It’s a mess.

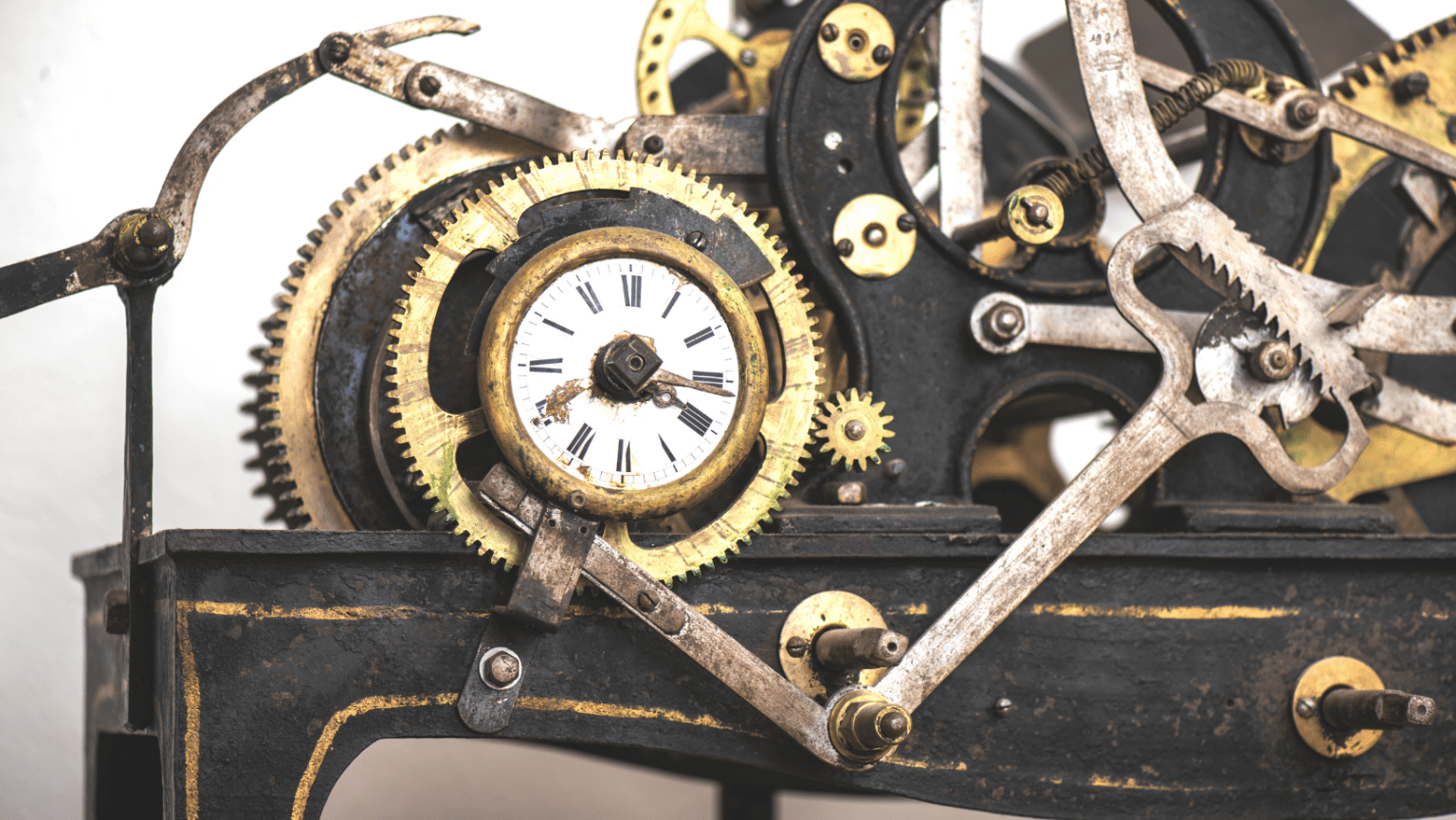

When the first mechanical clocks appeared—likely in Northern Italy or Southern Germany—they were huge, clunky iron frames. They didn't even have faces. No hands. No "12" or "6." They were just machines designed to strike a bell. In fact, the word "clock" comes from the Latin clocca, which literally means "bell."

The Mystery of the First Ticks

We don't actually know who the "inventor" was. History lost the name.

We have records of a clock built for the Abbey of St. Albans by Richard of Wallingford in the 1320s. He was a mathematical genius who was also suffering from leprosy. His clock was insanely complex, showing the moon’s phases and the tides. But he wasn't the first. References to "horologia" start popping up in the late 1200s.

When these pioneers were calibrating their creations, they weren't looking for "12:00 PM." They were looking for the "Solar Mean."

💡 You might also like: I’m Not a Human Vigilante: Why AI Ethics and Safety Guardrails Are Breaking the Fourth Wall

The Equation of Time

Here is the thing most people miss: The sun is actually a terrible timekeeper. Because the Earth’s orbit is an ellipse and our axis is tilted, the sun is sometimes "fast" and sometimes "slow." A "solar day" (noon to noon) can vary by several seconds throughout the year.

Early clockmakers discovered that their mechanical clocks, which ticked at a steady rate, would gradually drift away from the sundial. This gap is called the Equation of Time. By the 1600s, people like Christiaan Huygens—who invented the pendulum clock—realized they had to decide: Do we follow the sun, or do we follow the machine?

We chose the machine. We invented "Mean Time." We basically told the universe its orbits were too inconsistent for our schedules, so we averaged them out.

Why 12? Why Not 10?

If you were starting from scratch, you might choose a decimal system. Ten hours in a day? It makes sense mathematically. But we inherited our time from the Babylonians.

They loved the number 60. It’s highly divisible. You can divide 60 by 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20, and 30. It’s the perfect number for fractions. When the first mechanical clocks were calibrated, they adopted this sexagesimal system.

The day was split into two 12-hour blocks because ancient Egyptians used a "duodecimal" system based on the knuckles of the fingers (excluding the thumb). You have 12 knuckles on one hand. Use your thumb to count them. It’s a built-in calculator.

So, when they invented the clock, it was "twelve o'clock" because of a finger-counting habit from 3,000 years prior.

The Standardization Chaos

Fast forward to the 1800s. Clocks were everywhere, but they were all doing their own thing.

In the United States, there were over 300 different local times. Every railroad station had a different clock based on whenever the sun peaked over their specific roof. It was a nightmare for train schedules. Head-on collisions happened because two engineers thought they were on the same track at different times.

On November 18, 1883, the "Day of Two Noons," the railroads forced everyone to sync up. They created Time Zones. People were furious. Some preachers actually claimed that "Standard Time" was an attempt to change the laws of God and the nature of the sun.

But the machines won. The "time" when they invented the clock finally became the same time for everyone else, regardless of where the sun was.

Precision and the Atomic Age

Today, we don't use the sun or gears. We use atoms.

👉 See also: Clean Install macOS: Why You Should Probably Do It (And How Not To Mess It Up)

Since 1967, the second has been defined by the vibrations of a Cesium-133 atom. Specifically, $9,192,631,770$ oscillations per second. This is the ultimate "time" that the first inventors were searching for. We’ve reached a point where our clocks are more accurate than the Earth itself. The Earth’s rotation is actually slowing down due to tidal friction, so we occasionally have to add "Leap Seconds" to keep our atomic clocks from getting too far ahead of the planet.

It’s a strange reversal. We started by trying to make a machine that matched the Earth. Now, we have to occasionally stop the machine to let the Earth catch up.

Misconceptions About Early Timekeeping

A lot of people think the first clocks were small, like pocket watches.

Not even close. The first mechanical clocks were the size of small rooms. They were massive, forged iron beasts kept in the "clock tower" of a cathedral or town hall. They had no hairsprings, so they were incredibly inaccurate, often losing or gaining 15 to 30 minutes a day.

You didn't "check the time" in 1350. You "heard" the time when the bell rang.

- The "Pocket Watch" Myth: Portable watches didn't really exist until Peter Henlein started making "Nuremberg Eggs" in the early 1500s. Even then, they were status symbols that barely worked. You wore them around your neck, and they were basically jewelry that hummed.

- The Minute Hand: For a long time, clocks only had an hour hand. Why? Because the clocks were so inaccurate that a minute hand was a lie. There was no point in showing minutes if the clock was 20 minutes off anyway.

- The Pendulum: We didn't get truly accurate time until 1656. Before the pendulum, a clock was basically a sophisticated toy.

What You Can Do With This Knowledge

Understanding the history of the clock changes how you view your day. We treat time like an objective, physical constant—like gravity. But time as we "know" it (hours, minutes, time zones) is a human construct. It’s a collective agreement.

Practical Steps for Your "Time"

- Check your drift: Even your digital devices sync to a central server. Take a moment to look up "Time.is" to see exactly how synchronized your life is to the atomic standard.

- Solar vs. Civil: Find out your "Local Apparent Noon." There are calculators online where you enter your GPS coordinates, and it tells you when the sun is actually at its peak for you. It’s rarely 12:00 PM.

- Appreciate the Gear: If you own a mechanical watch, realize you are carrying a direct descendant of those 14th-century cathedral monsters. The "escapement"—the part that goes tick-tick-tick—is one of the most important mechanical inventions in human history.

The next time someone asks you what time it was when the clock was invented, tell them it was exactly whenever the sun said it was. We’ve just spent the last seven hundred years trying to get the machines to agree with the sky, only to end up with machines that are more perfect than the heavens themselves.

Everything we do today—from GPS navigation to high-frequency stock trading—relies on the fact that we finally answered that riddle. We stopped guessing what time it was and started defining it.