Walk up to the base of the Great Pyramid of Giza. It’s heavy. Not just the limestone, which weighs millions of tons, but the sheer weight of the history pressing down on you. You’ve likely heard the standard answer in third grade: they were tombs. That’s the baseline. But honestly, if you spend any time talking to an actual Egyptologist like Mark Lehner or Zahi Hawass, you realize that "tomb" is a massive oversimplification that misses the point of why these things dominated the skyline for millennia.

So, what were pyramids for?

They were engines. Not mechanical ones, obviously, but spiritual and political machines designed to keep the universe from falling apart. To the ancient Egyptians, the Pharaoh wasn't just a guy in a fancy hat; he was a living god, the bridge between the Nile and the heavens. When he died, the bridge couldn't just collapse. The pyramid was the permanent physical insurance policy that he would make it to the afterlife, join the sun god Ra, and keep the seasons turning for the rest of eternity.

More Than Just a Stone Box for a Dead Body

We have this modern habit of looking at ancient structures through a 21st-century lens. We see a big stone building and think "mausoleum" or "monument." But the Old Kingdom Egyptians didn't think like that. To them, death was a transition, a dangerous journey through the underworld.

The pyramid was a launchpad.

Specifically, the "True Pyramid" shape—the one with the smooth, sloping sides—is thought to represent the benben stone, the first mound of earth that rose from the primordial waters at the beginning of time. It’s also a physical representation of the sun’s rays. If you’ve ever been to Cairo on a dusty afternoon, you’ve seen the way the sun breaks through the clouds in solid, triangular shafts. The pyramid was a literal stone version of those rays, a ramp for the King’s soul to climb back to the stars.

The Resurrection Machine and the Ka

Let’s get into the weeds of Egyptian theology for a second because it’s weird and beautiful. They believed humans had multiple parts of the soul. There was the Ka (your life force) and the Ba (your personality). For the Ka to survive after death, it needed a place to live. It needed food, drink, and a recognizable body.

👉 See also: Why Cahir County Tipperary Ireland Is Actually Worth More Than a Quick Pit Stop

If the body rotted, the Ka died. If the Ka died, the Pharaoh couldn't do his job in the afterlife.

This is why the burial chamber is often hidden deep within or under the mountain of stone. It wasn't just to hide from grave robbers—though that was a major concern—but to create a "Place of Eternity." When you ask what were pyramids for, you’re really asking about the survival of the Egyptian state. If the Pharaoh successfully transitioned, the Nile would flood every year. If he didn't? Chaos. Famine. The end of the world. No pressure, right?

It Wasn't Just the Pyramid (The Complex Matters)

People usually focus on the big triangle. That’s a mistake. A pyramid was just one part of a massive "Pyramid Complex."

Think of it like a campus. You had the Valley Temple down by the water, the Causeway (a long, covered walkway), and the Mortuary Temple right up against the pyramid. This is where the action happened. Priests would perform daily rituals and leave food offerings for the dead King for decades, sometimes centuries, after he died.

- The Valley Temple: This is likely where the mummification happened. The "Opening of the Mouth" ceremony, which allowed the spirit to breathe and speak again, was the big finale here.

- The Causeway: A transition zone. These walls were often covered in relief carvings showing the King’s triumphs.

- The Mortuary Temple: The active site of worship.

It was a living, breathing economic hub. Thousands of people lived nearby in "pyramid cities" just to support the cult of the dead King. They baked bread, brewed beer, and kept the records. It was basically the biggest employer in the country.

The "Star Alignment" Theory: Fact or Fiction?

You’ve probably seen the History Channel specials at 2 AM claiming the pyramids were power plants or alien navigation beacons. Let’s be real: there is zero archaeological evidence for that. None.

However, there is a very real, very human connection to the stars. The "Air Shafts" in the Great Pyramid of Khufu aren't for air. They point toward specific celestial bodies: Orion’s Belt and the North Star (Thuban, at the time). The Egyptians were obsessed with the "Imperishable Stars"—the ones that never set below the horizon. They wanted the King to become one of those stars.

It’s a sophisticated blend of architecture and astronomy. They used the stars to align the pyramids with terrifying precision. The Great Pyramid is aligned to true north within a fraction of a degree. They didn't have GPS. They had string, water levels, and a very deep understanding of the sky.

The Economic Engine: Why Build Something So Big?

Building a pyramid was a flex. It was a way to unify a country that was still relatively young. By dragging 2.5-ton blocks across the desert, the population wasn't just working; they were participating in a national project.

Contrary to popular belief (and old Hollywood movies), the pyramids weren't built by slaves. We know this because we found the workers' villages. We found their medical records—they had bone surgery and high-protein diets. They were paid in rations. For a farmer whose fields were underwater during the Nile's flood season, a government job building the King's "Eternal House" was a pretty good deal. It created a sense of national identity.

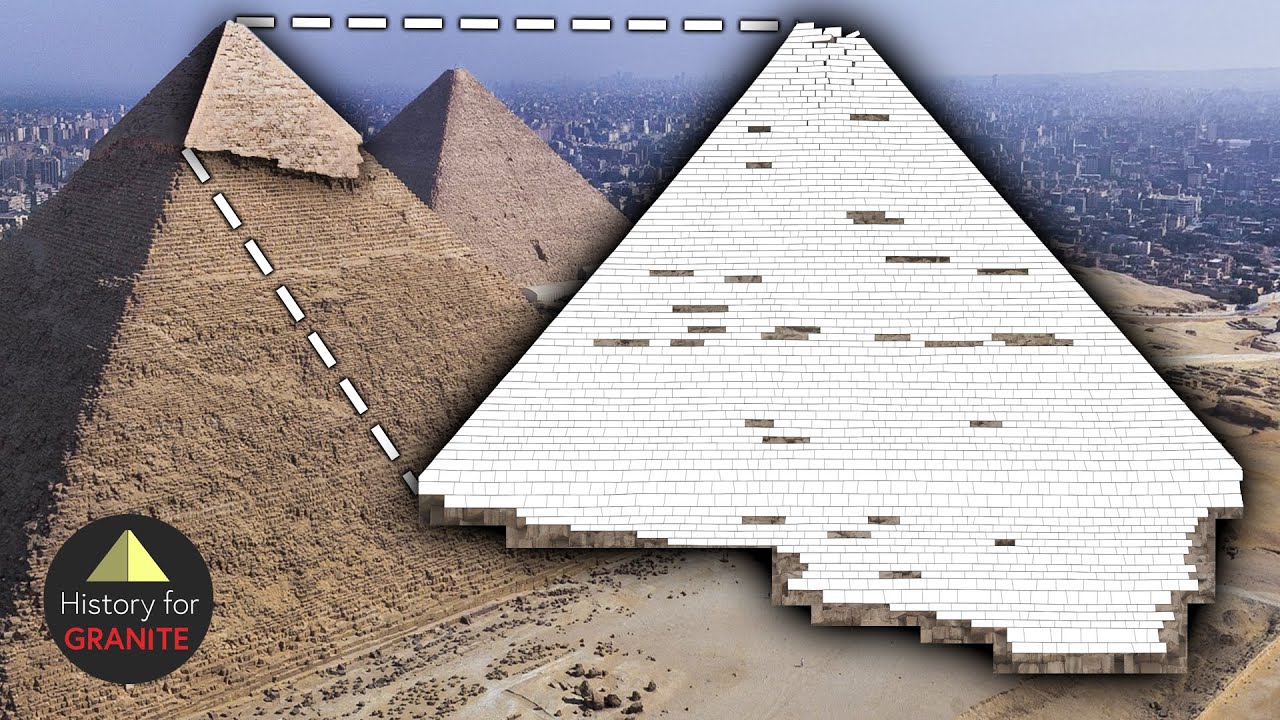

The Evolution of the Design

They didn't just wake up and know how to build the Great Pyramid. It was a process of trial and error that almost ended in disaster.

- Mastabas: Simple, flat-topped mud-brick tombs.

- The Step Pyramid (Djoser): Imhotep (the first named architect in history) had the bright idea to stack mastabas on top of each other. It was a stairway to heaven.

- The Bent Pyramid (Sneferu): They started at a 54-degree angle, but the structure started cracking under its own weight. They had to panic-adjust the angle to 43 degrees halfway up. It looks wonky, but it’s still standing.

- The Red Pyramid: Sneferu’s second try. The first "true" smooth-sided pyramid.

- The Great Pyramids of Giza: The peak of the craft.

What Most People Get Wrong

People think the pyramids are full of mummies. They aren't. Almost every pyramid was looted in antiquity. By the time modern archaeologists got there, the gold was gone, the mummies were destroyed, and the "curse" was mostly just a way to keep tourists from touching the walls.

Another misconception: the pyramids are in the middle of a remote desert. They aren't. The city of Giza has grown so much that there’s a Pizza Hut literally across the street from the Sphinx. It’s a jarring reminder that these "ancient" structures have been part of a living landscape for 4,500 years.

How to Understand Them Today

If you want to actually "get" what the pyramids were for, don't just look at the stones. Look at the intent. They were a massive, nation-wide scream against the finality of death. They were a way to say that the order of the world—the sun rising, the river flooding, the social hierarchy—was permanent.

💡 You might also like: Where Is Amelia Island Located in Florida: What Most People Get Wrong

Next Steps for Your Research:

- Look into the Pyramid Texts: These are the oldest religious writings in the world, found on the walls of later pyramids like Unas. They explain the spells and chants used to help the King navigate the afterlife.

- Study the Workers' Village at Giza: Research the work of Dr. Mark Lehner. It completely changes the narrative from "slave labor" to "organized national workforce."

- Compare the Pyramids to the Valley of the Kings: Later Pharaohs realized pyramids were basically giant "STEAL FROM ME" signs for robbers. They switched to hidden underground tombs, but the purpose remained the same.

The pyramids weren't just for the dead. They were for the living, a way to organize a civilization around a single, unified goal of immortality. When you stand in their shadow, you're not just looking at a tomb; you're looking at the birth of the state.