You’ve probably heard the standard classroom answer. Ask most people and they’ll confidently tell you that it all kicked off in 1760. Or maybe 1750 if they’re feeling spicy. But history is rarely that neat. It doesn't just "start" like a race at the sound of a gun. Honestly, pinpointing exactly when did industrialisation begin is more about tracking a slow, messy, and often accidental shift in how humans interact with the planet than finding a single date on a calendar.

It was a vibe shift. A massive, soot-covered, world-altering vibe shift.

Before the steam engines and the smog, life was cyclical. You grew what you ate. You made your own clothes. If you needed power, you used a horse, a water wheel, or your own muscles. Then, something broke. Or maybe something clicked. Between the mid-18th century and the early 19th century, Great Britain—and eventually the rest of the world—flipped a switch from organic energy to fossil fuels.

The 1760 Myth and the Reality of Slow Growth

Historian T.S. Ashton famously pinned the start date at 1760. It’s a convenient number. It aligns roughly with the accession of George III and the patenting of some pretty famous gadgets. But if you were a farmer in 1765, you probably didn't notice the world changing. You were still tilling soil.

Nicholas Crafts, a massive name in economic history, actually challenged the idea of a sudden "take-off." He looked at the data and realized that British GDP growth during the late 1700s was actually pretty sluggish. It wasn't a rocket ship. It was a slow-moving train that took decades to pick up speed.

So, if you’re looking for a specific Tuesday when everything changed, you won't find it. What you will find is a series of "micro-inventions" that reached a tipping point.

Why Britain? (And Why Then?)

It wasn't just luck. It was a weird cocktail of geography, politics, and greed.

First, Britain was sitting on a mountain of coal. Literally. In places like Newcastle, the coal seams were shallow and easy to get to. This is crucial because wood was getting expensive. Britain had chopped down most of its forests to build ships and heat homes. They needed a new fuel, and coal was the smelly, high-energy answer.

But there was a problem. When you dig deep for coal, the mines fill up with water. You can't mine if you're underwater. This desperation led to the birth of the atmospheric engine.

📖 Related: Ekati Diamond Mine Northwest Territories: Why This Arctic Giant Still Matters in 2026

The Newcomen and Watt Revolution

In 1712—way before the "official" start date—Thomas Newcomen built the first practical steam engine to pump water out of mines. It was massive. It was inefficient. It was basically a giant piston that moved up and down because of a vacuum created by condensing steam.

It worked, though.

Then came James Watt. In 1769, Watt patented a separate condenser. This sounds like a minor technical tweak, but it was the "iPhone moment" of the 18th century. It made steam engines efficient enough to be used anywhere, not just at the mouth of a coal mine. Suddenly, you didn't need a river to power a mill. You could put a factory in the middle of a city.

When did industrialisation begin? Many scholars argue it truly started the moment Watt’s engine became commercially viable in the 1770s through his partnership with Matthew Boulton. Boulton wasn't just a financier; he was a hype man. He famously told King George III, "I sell here, Sir, what all the world desires to have—Power."

Textiles: The Engine of Change

While steam was the heart, cotton was the blood.

🔗 Read more: American Beverage Depot LLC: What’s Actually Happening Behind the Scenes

The textile industry was the first to go "industrial" in the way we recognize today. Before this, "spinning" was something women did at home—the original "cottage industry." It was slow. Then came the disruptors:

- James Hargreaves’ Spinning Jenny (1764): Allowed one person to spin multiple spools of thread at once.

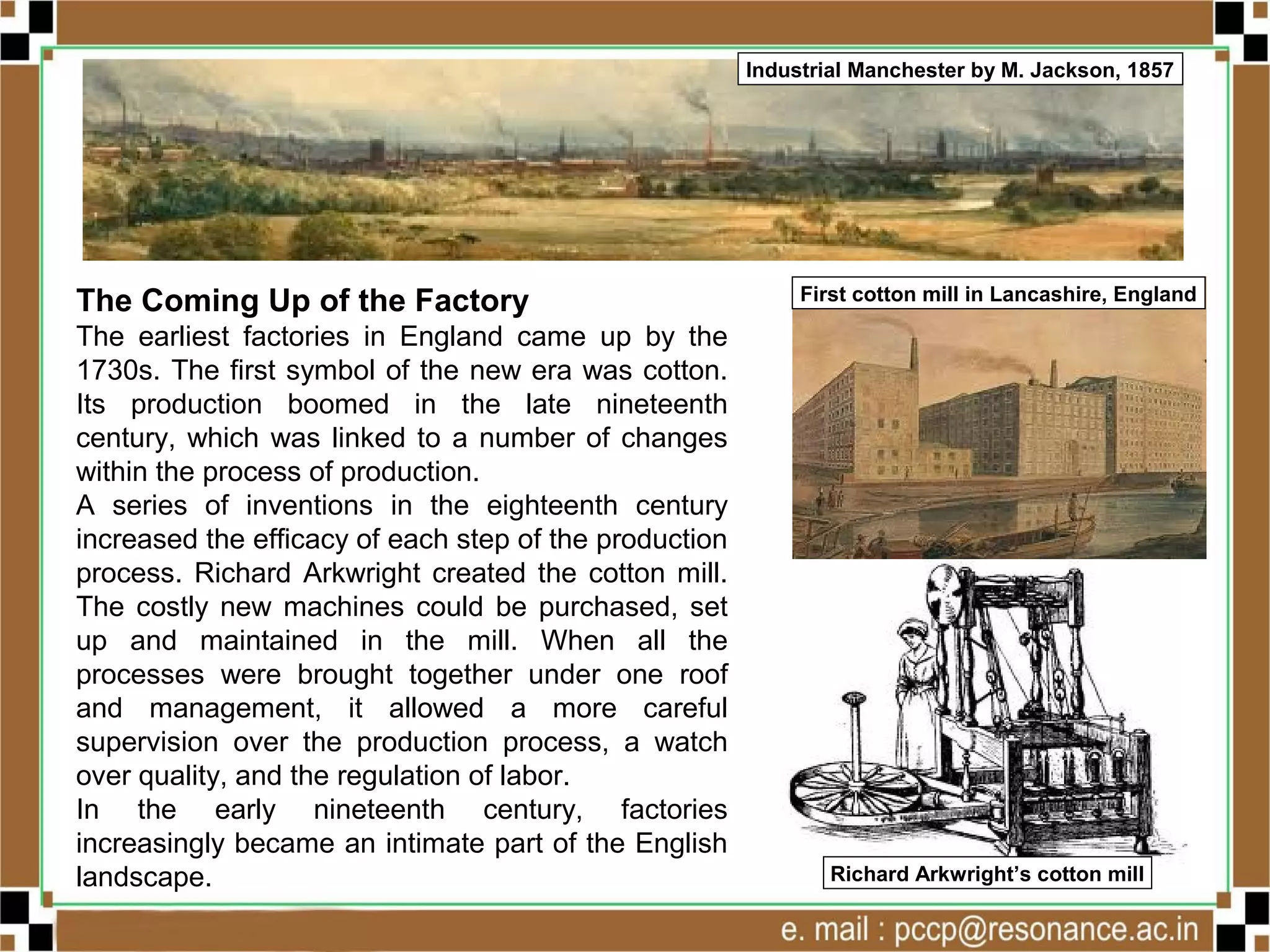

- Richard Arkwright’s Water Frame (1769): Used water power to spin even stronger thread. Arkwright was kind of a ruthless boss, basically inventing the modern factory system at Cromford Mill.

- Samuel Crompton’s Mule (1779): Combined the best of both worlds.

By the 1780s, the output of British cotton was exploding. It was cheaper, stronger, and more plentiful than anything the world had ever seen. This had a dark side, obviously. The hunger for cotton fueled the expansion of slavery in the American South. You can't talk about industrialisation without talking about the human cost. It wasn't just gears and cogs; it was exploitation on a global scale.

The Great Divergence

Why didn't this happen in China or India? Both were incredibly advanced. China had been using coal for centuries. They had massive trade networks.

Kenneth Pomeranz, in his landmark book The Great Divergence, argues it came down to "coal and colonies." Britain had easy-to-reach energy and a massive captive market in its colonies. China’s coal was far from its manufacturing centers in the south. Geography is destiny, or at least a very strong suggestion.

The Second Wave: 1870 and Beyond

If the first phase was about coal, steam, and cotton, the "Second Industrial Revolution" changed the game again. This is usually dated around 1870.

This was the era of steel, chemicals, and electricity.

Henry Bessemer figured out how to mass-produce steel cheaply in 1856. Before him, steel was a luxury. Afterward, it was the skeleton of the modern world. Skyscrapers, massive bridges, and thousands of miles of railway tracks became possible. Then came Edison and Tesla. Electricity turned the "dark, satanic mills" into 24-hour operations.

This is when industrialisation stopped being a British quirk and became a global phenomenon. Germany and the United States started outperforming Britain. They invested in "R&D" (Research and Development) before that was even a term.

What Most People Get Wrong

People think industrialisation was a "good" thing that happened all at once.

It was actually pretty miserable for the people living through it. Life expectancy in industrial cities like Manchester or Liverpool plummeted. In the 1840s, the average life expectancy for a laborer in Bethnal Green was just 16 years. Disease, overcrowding, and 14-hour workdays were the norm.

We also tend to think of it as a purely technological event. It wasn't. It was an institutional event. It required patent laws so inventors could get rich. It required a banking system that could lend massive amounts of capital. It required a legal system that recognized "corporations" as people. Without the boring stuff like contracts and insurance, the machines would have just sat in sheds.

👉 See also: Finding the Amazon Credit Card Payment Phone Number Without Getting Scammed

Identifying the True Starting Point

If you're writing a paper or just want to win a pub quiz, here is the nuanced breakdown of when things actually shifted:

- The Prelude (1700–1712): Newcomen’s engine proves that we can use fossil fuels to do mechanical work.

- The Traditional Start (1760): A period of rapid invention in textiles (Hargreaves, Arkwright).

- The Point of No Return (1776–1785): Watt’s steam engine becomes commercially successful, and the first "modern" factories emerge.

- The Global Spread (1830s): The railway age begins with the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, effectively "shrinking" the world.

Taking Action: How to Understand Industrialisation Today

You shouldn't just look at this as dusty history. The processes that started in 1760 are still happening, just in different sectors.

- Look for "General Purpose Technologies": Just as the steam engine was a GPT that changed everything, AI and CRISPR are doing the same today. History doesn't repeat, but it definitely rhymes.

- Analyze Energy Transitions: We are currently in the middle of a "reverse" industrial revolution—trying to move from fossil fuels back to "organic" (but high-tech) energy like solar and wind. Understanding how hard it was to switch to coal helps you understand why it's so hard to switch away from it.

- Trace the Supply Chain: Pick a product in your house. A t-shirt. A phone. Try to trace the path it took. You'll see the ghosts of the 18th-century factory system in every step of the global logistics chain.

Industrialisation didn't start with a single inventor. It started when a specific set of economic needs met a specific set of geographical lucky breaks. It was a messy, often violent transition that redefined what it means to be human. We stopped being part of nature and started trying to manage it. We're still dealing with the consequences of that shift today.