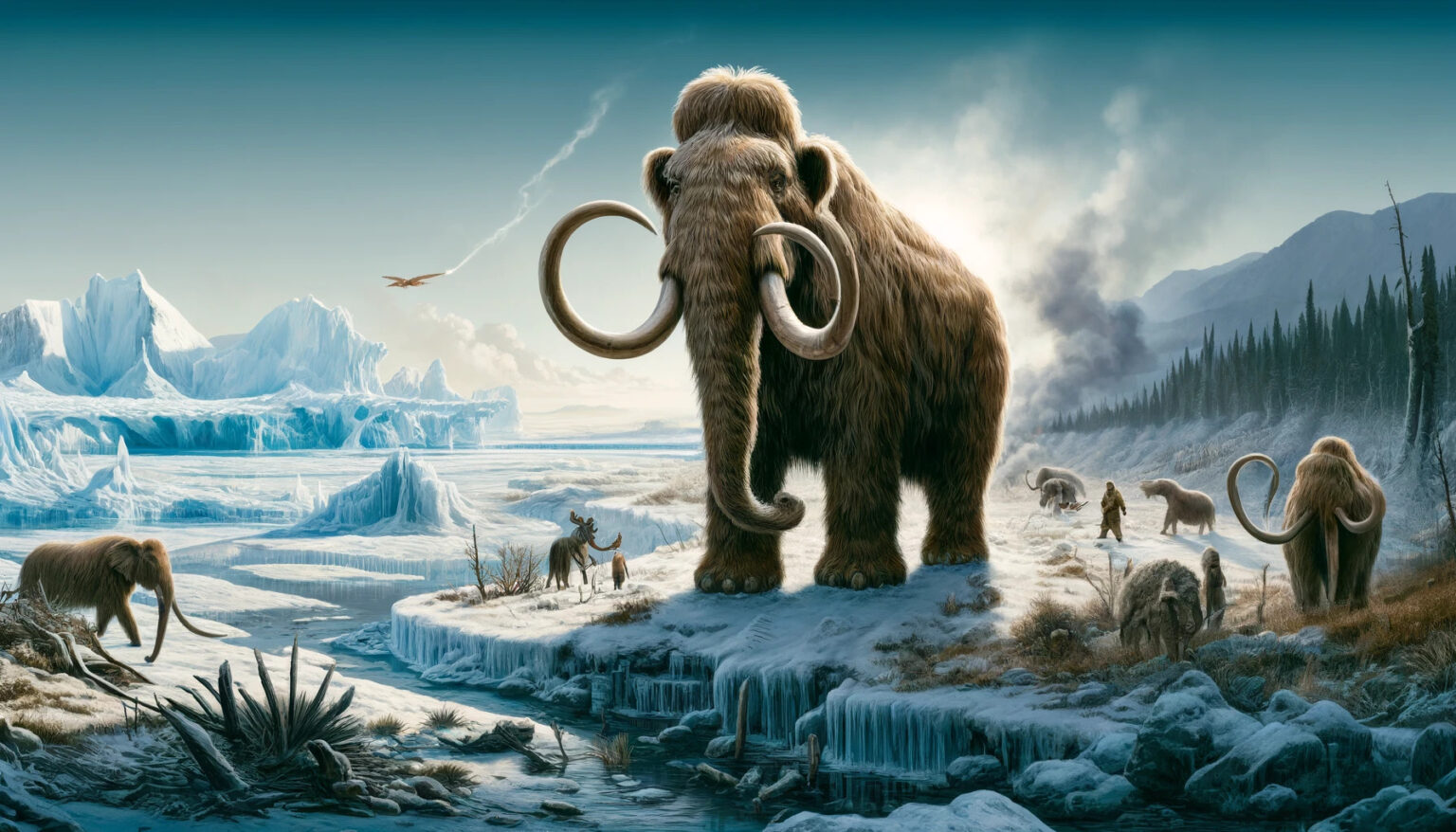

You probably think the last mammoth died out during the Ice Age. It’s the classic mental image: a lonely, shaggy beast trudging through a blizzard while a group of cavemen with flint spears closes in for the kill. It feels like ancient history. It feels like another world entirely. But the timeline of when did mammoth go extinct is actually much weirder and more recent than your middle school history books suggested.

While the Great Pyramids were being built in Egypt, woolly mammoths were still roaming an island in the Arctic Ocean. That’s not a metaphor. It’s a literal, geological fact.

The Timeline Most People Miss

Most of the world's mammoth population vanished about 10,000 years ago. This was the end of the Pleistocene, a chaotic time when the planet was warming up and the massive "mammoth steppe"—a grassy, cold tundra that once stretched from France to Canada—was turning into boggy forests and mossy wetlands. For a long time, scientists basically checked the "extinct" box right there.

📖 Related: Days Since Jan 20 2025: A Real-Time Look at Where We Stand

But extinction isn't usually a single event. It's a slow, agonizing fade.

Small pockets of these giants survived in isolation. On St. Paul Island, off the coast of Alaska, a tiny population hung on until about 5,600 years ago. But the real record-breakers were on Wrangel Island, a desolate scrap of land in the East Siberian Sea. Researchers like Love Dalén from the Centre for Palaeogenetics have used advanced DNA sequencing to prove that mammoths lived there until roughly 2,000 BC.

To put that in perspective, the Pharaoh Khufu was commissioning the Great Pyramid of Giza around 2500 BC. The mammoths outlasted the construction of one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. They were still breathing while the Minoan civilization was rising in Crete.

Why Did They Finally Give Up the Ghost?

So, if they survived the end of the Ice Age, why did they die out at all? It wasn't just one thing. It was a "perfect storm" of bad luck.

On Wrangel Island, the population was tiny. Maybe 300 to 500 individuals at its peak. When you have a group that small, inbreeding becomes a massive problem. Geneticists have looked at the DNA of these last survivors and found "deleterious mutations." Basically, their genetic code was falling apart. They were losing their sense of smell, their fur was changing texture, and they were likely suffering from heart defects and developmental issues.

They were the "living dead" long before the last one actually fell.

📖 Related: Jake Thomas Patterson Now: Where the Jayme Closs Kidnapper is Today

Climate Change vs. Human Hunters

This is the big debate in paleontology. Was it us or the weather?

- The Climate Case: As the world warmed, the high-protein grasses the mammoths ate were replaced by mosses and shrubs. Mammoths were huge. They needed to eat a staggering amount of food just to maintain their body heat. Imagine trying to fuel a semi-truck with AA batteries. It doesn't work.

- The Overkill Hypothesis: This is the idea that humans followed mammoths across the Bering Land Bridge and hunted them into oblivion. We were efficient. We were organized. And we were hungry.

Honestly, it was probably both. Climate change pushed them into tiny geographic corners, and then humans—or just a single bad season of drought or a freak icing event—delivered the final blow.

The Wrangel Island Mystery

The end on Wrangel Island is particularly haunting. There is no evidence of humans arriving on the island until after the mammoths were already gone. This suggests that the very last mammoths on Earth didn't die at the end of a spear. They died because of a lack of fresh water or perhaps a sudden "rain-on-snow" event.

In the Arctic, if it rains in the middle of winter, the water freezes into a thick layer of ice over the snow. The mammoths couldn't kick through the ice to get to the grass underneath. They starved. An entire species, reduced to a few dozen starving animals on a frozen rock, unable to reach the food right under their feet.

It’s a grim way to go.

Could We Bring Them Back?

Because we have found so many "mummies"—mammoths frozen in the Siberian permafrost with skin, hair, and even stomach contents intact—we have their full genome. Companies like Colossal Biosciences are currently working on "de-extinction."

They aren't exactly making a pure mammoth. They are using CRISPR technology to edit the DNA of Asian elephants, inserting mammoth genes for thick hair, subcutaneous fat, and small ears. The goal is to create a "proxy" species that can live in the Arctic and help restore the ecosystem.

Why? Because mammoths were ecological engineers. By trampling moss and knocking down trees, they kept the grasslands healthy. Grasslands reflect more sunlight than dark forests, which keeps the permafrost frozen. In a weird twist of fate, the answer to our current climate crisis might involve resurrecting a ghost from the last one.

The Lessons of the Mammoth

Understanding when did mammoth go extinct isn't just about trivia. It’s a warning. It shows us how quickly a dominant, global species can be reduced to a few broken individuals on a lonely island.

- Isolation is a death sentence. Small populations lose the genetic diversity needed to survive environmental shifts.

- The "Pyramid Paradox" matters. We often view history in silos, but the overlap between "prehistoric" animals and "ancient" civilizations is much larger than we think.

- Ecosystems are fragile. When the mammoth left, the entire "Mammoth Steppe" collapsed, changing the face of the Northern Hemisphere forever.

If you want to dive deeper into this, look up the research papers by Patrícia Pečnerová. She has done incredible work on the genomic melting of the Wrangel Island population. It’s fascinating, heartbreaking stuff that reminds us that extinction isn't a myth—it's a process that is still happening today.

🔗 Read more: Latest United States of America News: What Actually Happened This Week

Check your local natural history museum's digital archives for "Pleistocene Megafauna." Most major museums, like the American Museum of Natural History, now have high-resolution scans of mammoth remains that let you see the dental wear patterns that prove just how hard those last years were. Taking a look at the actual physical evidence makes the timeline feel much more real.