Talking about death is weird. It’s heavy, it’s awkward, and most of us would rather discuss literally anything else—like the weather or that new show on Netflix. But then someone brings up a "DNR," and suddenly the room feels very small.

Honestly, there is so much junk information out there about what a Do Not Resuscitate order actually does. You’ve probably seen the TV dramas. A doctor shocks a patient, the monitor beeps back to life, and everyone cheers. In the real world? It’s rarely that clean. Knowing when is a DNR appropriate isn't just about age or being "sick." It’s about a deeply personal intersection of medical reality and what you want your last moments to look like.

Let’s get one thing straight: a DNR isn’t a "do not treat" order. It’s not a signal for the nurses to stop bringing you water or for your doctor to ignore your pneumonia. It’s a specific instruction for one very specific moment: when your heart stops beating or you stop breathing. That’s it.

The Brutal Reality of CPR

Most people think CPR is a magic wand. We’ve been conditioned by Hollywood to believe it has a 70% or 80% success rate.

The data says otherwise.

For a healthy person who has a sudden accident, CPR can be a lifesaver. But for someone with a terminal illness or advanced frailty? The success rate of leaving the hospital alive after CPR can drop to less than 5%.

According to the American Medical Association (AMA), a DNR is appropriate for anyone at risk of cardiac arrest where the "benefits" of resuscitation are outweighed by the trauma of the process. CPR is violent. It involves breaking ribs. It involves shoving tubes down a throat. It involves electrical shocks. If your body is already worn out by years of battling heart failure or stage IV cancer, that kind of physical trauma doesn't usually lead back to a "normal" life. It often leads to a ventilator in an ICU.

📖 Related: Fix It Fast Diet: Why People Still Chase This 10-Day Crash Strategy

When the Medical Math Shifts

Deciding if a DNR is right for you—or a parent—usually happens when the goal of care shifts from "curing" to "comfort."

Physicians often use what they call the "Surprise Question." They ask themselves, "Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 12 months?" If the answer is no, it’s probably time to talk about a DNR.

Scenarios where a DNR makes total sense:

- Terminal Illness: When a disease like metastatic cancer has reached a point where medical intervention can no longer change the outcome. In these cases, CPR just delays the inevitable and makes the process much more painful.

- Advanced Frailty: For very elderly patients, the body's ability to recover from the physical damage of chest compressions is minimal. The "recovery" might just mean living the rest of one's days in a persistent vegetative state or on a permanent breathing machine.

- Quality of Life Concerns: This is the big one. If your definition of a "good life" involves being able to recognize your family or live at home, and the medical odds say resuscitation will likely leave you with severe brain damage, a DNR is a tool to protect your dignity.

The "DNI" Confusion

You'll often hear DNR and DNI mentioned in the same breath. They aren't the same.

DNI stands for Do Not Intubate.

Some people are okay with chest compressions but they absolutely do not want a machine breathing for them for the next three weeks. You can actually have one without the other, though most people who choose a DNR also choose a DNI because the two procedures usually go hand-in-hand during a crisis.

Dr. Oracle, a clinical resource updated for 2026, notes that DNI orders should be separate if a patient is okay with temporary cardiac support but wants to avoid the long-term "hooked up to a machine" scenario. It’s about nuance. It’s about you being in the driver's seat.

Can You Change Your Mind?

Yes. Absolutely.

A DNR is not a suicide pact. It’s a medical order. If you’re going in for a minor surgery—say, a hip replacement—and you’re otherwise doing okay, you can actually suspend your DNR for the duration of the procedure.

Doctors at the Mayo Clinic emphasize that these documents should be reviewed every time your health status changes. If you were really sick last year but a new treatment worked and you're feeling great now? You can tear that paper up.

It’s also worth noting that in an emergency, if the paramedics don’t see the yellow form (or the specific purple one, depending on your state), they will perform CPR. They are legally required to try and save you unless they have that signed order in their hands. This is why having the conversation with your family is actually more important than the paperwork itself. If they don't know where the form is, it doesn't exist.

The Conversation Nobody Wants to Have

If you're wondering if it's the right time to bring this up with a loved one, look at the trajectory. Are the hospitalizations getting closer together? Is the "baseline" getting lower every month?

Palliative care experts suggest starting the talk with: "What are you most worried about?"

Usually, people aren't worried about dying. They’re worried about suffering. They’re worried about being a burden. Once you identify that, the DNR question becomes much easier to answer. It stops being about "giving up" and starts being about "choosing how to live" until the very end.

Actionable Next Steps

If you think a DNR might be appropriate for your situation, don't wait for a crisis to decide. Emergency rooms are terrible places for making life-altering ethical choices.

- Schedule a "Goals of Care" meeting: Ask your primary doctor or specialist for 20 minutes specifically to talk about advance directives. Don't let it be a footnote at the end of a check-up.

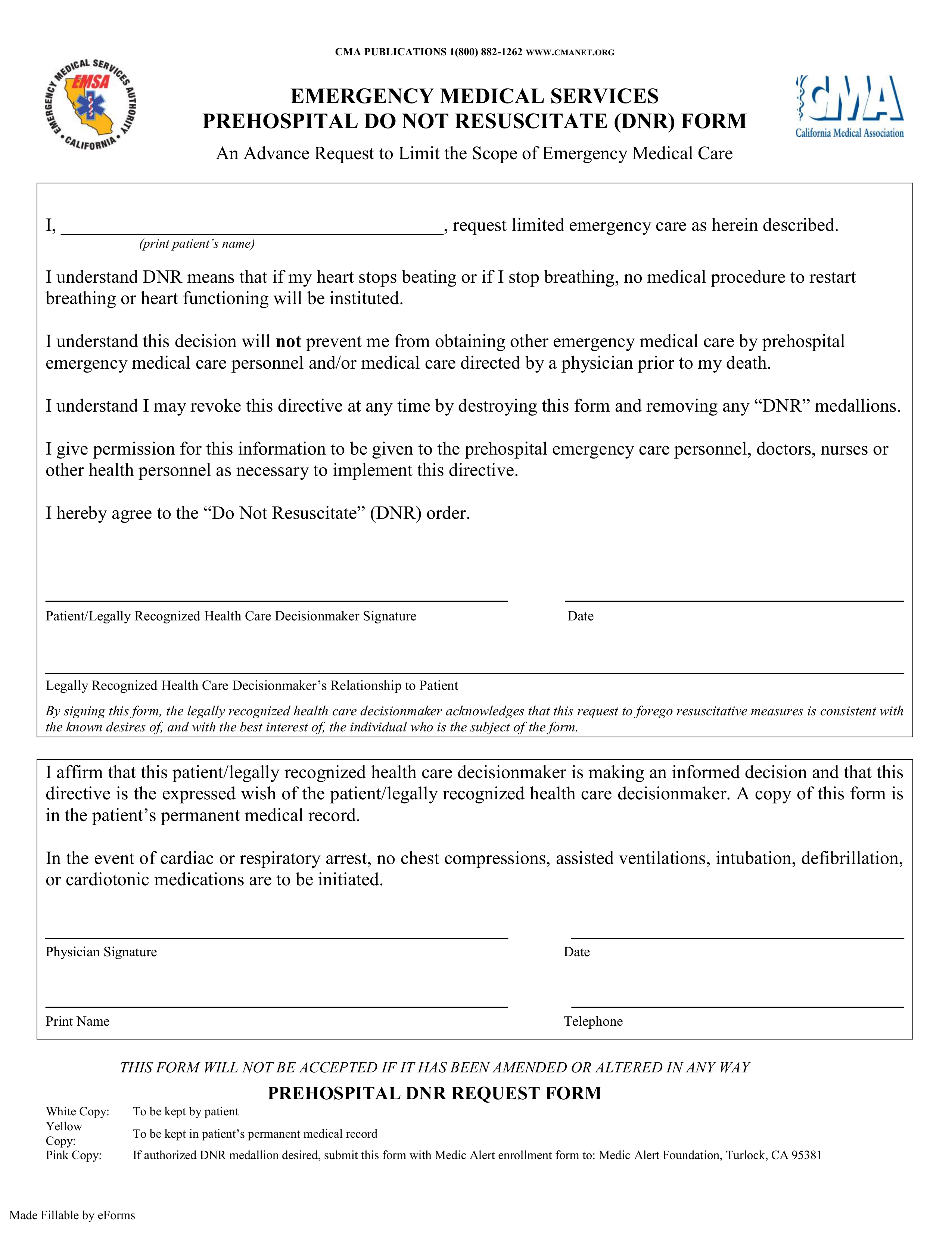

- Get the right form: A "Living Will" is not a DNR. You need a specific medical order signed by a physician (often called a POLST or MOLST depending on where you live).

- The Fridge Rule: In most states, EMS is trained to look on the refrigerator for medical alerts. Keep your signed DNR in a clear plastic sleeve on the fridge.

- Talk to your proxy: Make sure the person you’ve named as your Power of Attorney knows why you want a DNR. They are the ones who will have to stand their ground when things get chaotic.

- Digital backups: Ensure the order is scanned into your hospital’s electronic portal. If you’re at Cleveland Clinic or a similar system, they can flag this in your chart so it's the first thing a doctor sees in the ER.

A DNR is a gift of clarity for your family. It takes the weight of a "life or death" decision off their shoulders and keeps it where it belongs: with you.