If you look at a map of mountain lion habitat today, you’re basically looking at a ghost story. One that’s coming back to life. For a long time, the narrative was simple: we pushed them West, they stayed there, and the story ended at the Rocky Mountains. But nature doesn't really care about our maps or our neat little borders.

Mountain lions (Puma concolor) are the ultimate generalists. They don't just live in mountains, despite the name. They’re in the swamps of Florida, the deserts of Arizona, and the frozen forests of the Canadian Yukon. Honestly, they have the broadest range of any large wild land mammal in the Americas.

But seeing where they can live versus where they actually do live is a totally different ballgame.

The Disappearing Act and the Modern Comeback

A few hundred years ago, a map of mountain lion habitat would have covered almost the entire continental United States. Coast to coast. North to south. Then came the bounty hunters and the habitat fragmentation. By the mid-20th century, the Eastern Cougar was declared extinct, and the only cats left were clinging to the rugged terrain of the West and a tiny, struggling population in the Florida Everglades known as the Florida Panther.

Things changed.

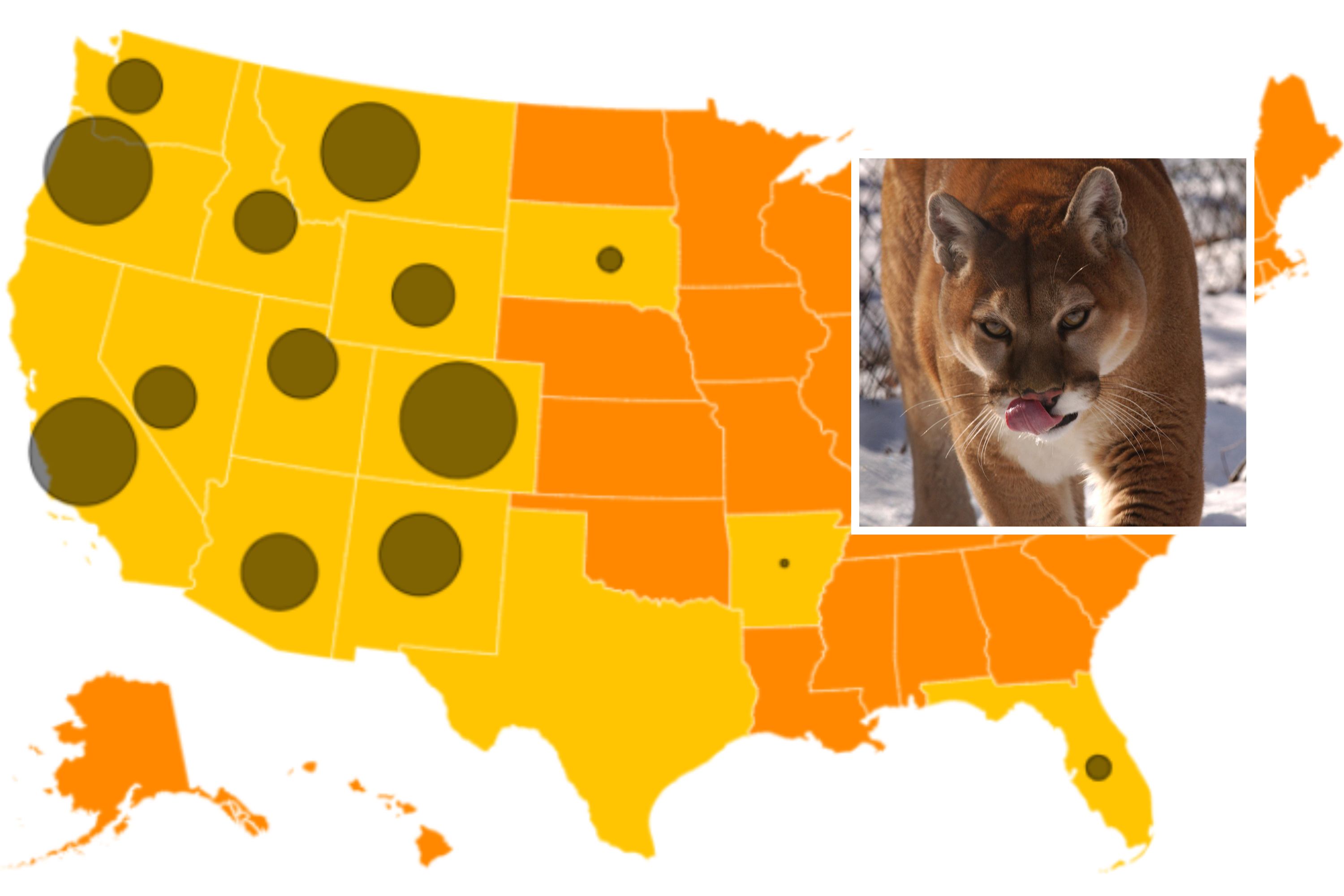

In the last few decades, these cats have been reclaiming ground. It’s not a fast process. It's slow. It’s methodical. Young males—the "dispersers"—are the ones pushing the boundaries. They’ve been spotted in Nebraska, Kansas, and even roaming the outskirts of Chicago. When you look at a modern map of mountain lion habitat, you see these "blobs" of established populations in the West, but then you see these long, thin lines stretching Eastward. Those are the corridors.

Wildlife biologists like Dr. Michelle LaRue and organizations like the Cougar Network have been tracking these sightings for years. It’s not just anecdotal anymore. It's data.

👉 See also: La temperatura en New York grados centigrados: Lo que nadie te dice sobre el clima real de la Gran Manzana

Reading the Map: What the Colors Actually Mean

When you look at a professional habitat map, you’ll usually see three distinct zones.

- Breeding Populations: This is the core. It’s the dark green or shaded areas on the map. This is where females are raising kittens. If you're in the Sierra Nevada or the Cascades, you're in the heart of it. These cats aren't just passing through; they own the place.

- Transient Corridors: These are the "maybe" zones. They look like veins on a map. A young male might travel 500 miles looking for a mate. He’ll cross highways, swim rivers, and hide in your suburban backyard. He’s on the map, but he’s not staying.

- Historical vs. Potential Habitat: This is the controversial part. Scientists use "Maximum Entropy" modeling (MaxEnt) to predict where cats could live based on deer density and forest cover. Basically, if there’s food and a place to hide, a mountain lion will consider it home.

The Mid-West is the current frontier. Places like the Black Hills of South Dakota act as a "stepping stone." Cats move from the Rockies to the Black Hills, and from there, they eye the Missouri River. It’s a literal bridge to the East.

Why a Map of Mountain Lion Habitat Is Never Finished

Nature is fluid.

Take the Santa Monica Mountains in California. If you saw a map of that area, it would look like an island. The 101 Freeway acts as a massive wall. The National Park Service has been studying the cats there—like the famous P-22 who lived in Griffith Park—and the map shows a terrifying reality of genetic isolation. Without "wildlife crossings," these maps become maps of extinction.

Then you have the Florida Panther. Their habitat map is a tiny, bruised thumb at the bottom of Florida. They’re hemmed in by development and oranges. But even there, there’s hope. Females have finally started crossing the Caloosahatchee River for the first time in decades.

That changes the map.

The Problem with "Confirmed" Sightings

Here’s a weird fact: Most "mountain lion" sightings in the East turn out to be golden retrievers, bobcats, or very large house cats. This is why a reliable map of mountain lion habitat only uses "Class 1" evidence. We’re talking carcasses, DNA, or clear photos.

A grainy video of a "black panther" doesn't count. Fun fact? There has never been a documented "black" (melanistic) mountain lion in North America. Ever. If someone tells you they saw a black cougar in the woods of Pennsylvania, they’re seeing things. Or they saw a very lost jaguar.

The Human Factor: Sharing the Map

Living within a mountain lion's range isn't like living with a bear. Bears are loud. They mess with your trash. Mountain lions are "ghost cats." You could live in their habitat for thirty years and never see one, even though they’ve seen you a dozen times.

💡 You might also like: Finding a Dog Carrier for Plane Travel That Won't Get You Rejected at the Gate

The map of where people live and where lions live is overlapping more every day. This leads to what experts call "Human-Wildlife Conflict."

But it’s not all bad news.

In places like the Bay Area or Los Angeles, people are learning to build around the map. We’re building the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing over the 101 Freeway—the largest in the world. This effectively expands the map of mountain lion habitat by connecting fragmented islands of land. It turns a dead-end on the map into a highway for biodiversity.

What Most People Get Wrong About Habitat

People think mountain lions need "wilderness."

They don't.

They need "connectivity." A lion can thrive in a patchwork of ranches and suburban greenbelts as long as it can move between them without getting hit by a car. They are remarkably tolerant of us, provided we don't corner them.

The real limiting factor on the map isn't the landscape; it's social tolerance. Can we handle having a 150-pound predator in our "viewshed"? In the West, the answer has been a tentative "yes" for a century. In the East, we’re still deciding.

The Future of the Map: The 2030 Outlook

If you look at the trends, the map of mountain lion habitat is going to continue its Eastward creep. The Great Lakes region is looking like a prime candidate for future recolonization. The Adirondacks in New York have the trees and the deer, but they’re missing the cats. For now.

Will we see a day when the map shows a solid line from the Pacific to the Atlantic again? Maybe not in our lifetime, but the biological groundwork is being laid.

Actionable Steps for Navigating Lion Country

If you live in or are traveling to an area highlighted on a mountain lion habitat map, you don't need to live in fear. You just need to be smart.

🔗 Read more: Finding Your Way Through the Map of Kowloon Walled City: Why It Still Fascinates Us

- Secure your perimeter: If you have livestock or pets, keep them in fully enclosed pens at night. Motion-activated lights help, but they aren't a silver bullet.

- Deer are the magnet: If your yard is a buffet for deer, it’s a buffet for lions. Landscaping that discourages deer will naturally discourage their predators.

- Hiking habits: Don’t hike alone at dawn or dusk. That’s "cat time." If you see one, don't run. Running triggers their chase instinct. Stand tall, look big, and make a lot of noise. Basically, be the most annoying thing in the woods.

- Contribute to the science: If you find a clear track or have a trail cam photo in an area where they aren't supposed to be, report it to your state’s Department of Natural Resources. Your data point could literally change the map.

Understanding the map of mountain lion habitat is about more than just knowing where to avoid a hike. It’s a blueprint for how we’re doing as stewards of the land. A map with big cats on it is a map of a healthy, functioning ecosystem. It means there’s enough room for the wild to breathe.

Stay aware of your surroundings when exploring the Western states or the expanding corridors of the Midwest. Keep your dogs on leashes in wooded areas, and always check local wildlife reports before heading into remote territory. The cats are out there, and for the first time in a century, their world is getting a little bit bigger.