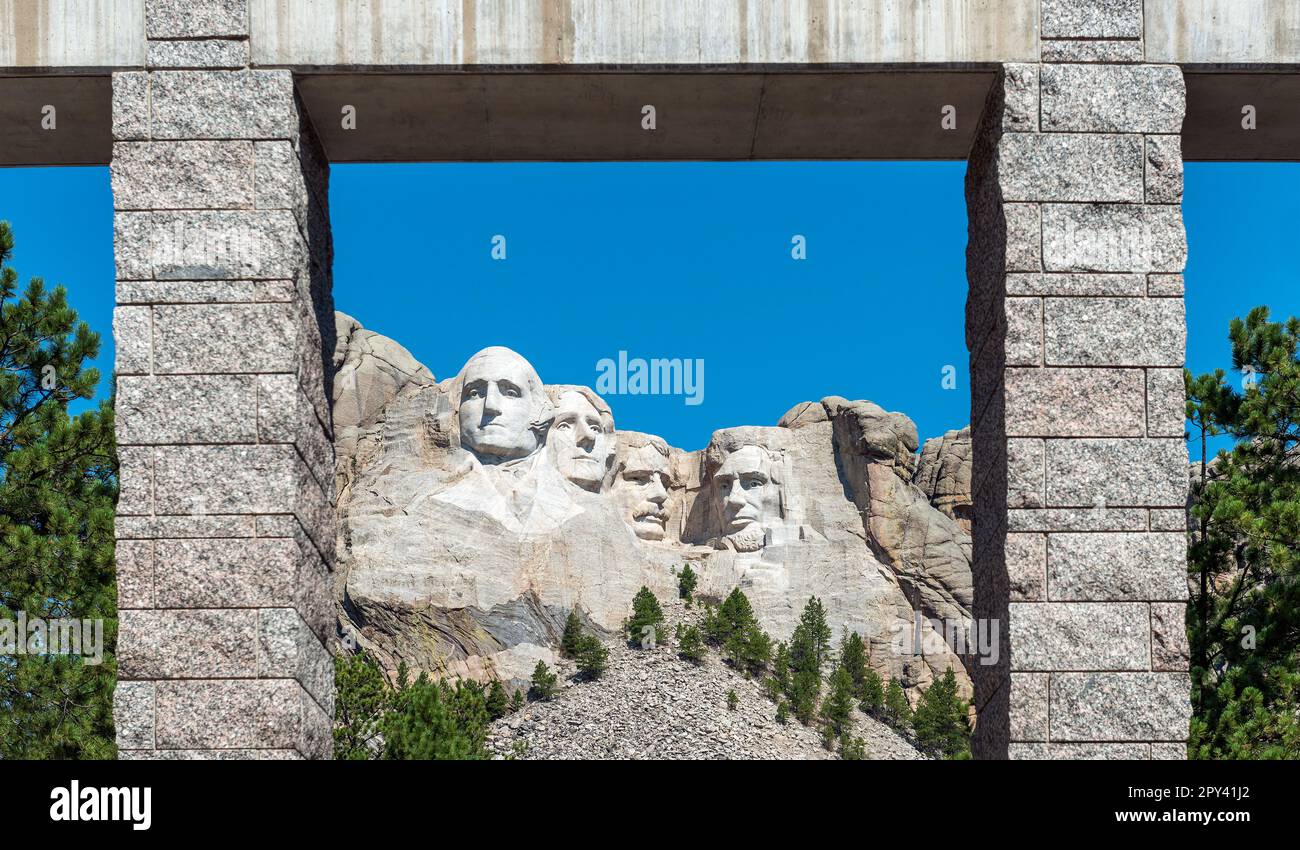

You’ve seen the postcards. You know the faces. Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt, and Lincoln staring out over the Black Hills of South Dakota with that stoic, eternal gaze. But when you ask who carved Mount Rushmore, the answer isn't just one guy with a chisel. It’s a messy, loud, dangerous story involving a temperamental artist, hundreds of out-of-work miners, and enough dynamite to level a small city.

Most people think of Gutzon Borglum. He's the name in the history books. He was the visionary, sure, but he was also a man who spent as much time arguing with the federal government as he did looking at the mountain. The real work—the bone-rattling, lung-clogging labor—was done by about 400 local workers. These weren't "artists." They were drillers and "powdermen" who just needed a paycheck during the Great Depression. They didn't come to create a masterpiece; they came because it paid better than the struggling gold mines nearby.

The Man with the Ego: Gutzon Borglum

Gutzon Borglum was a complicated character. To understand who carved Mount Rushmore, you have to understand his obsession. He was a student of Rodin, and he wanted to do something "American" in scale. Big. Massive. Before Rushmore, he was working on Stone Mountain in Georgia, but he got fired after a massive fallout with the sponsors. Legend has it he even smashed his clay models so they couldn't use his designs.

He was brilliant. He was also a nightmare to work for.

📖 Related: St. Augustine Beach & Tennis Resort: What Really Makes This Place Different

Borglum wasn't just the sculptor; he was the promoter. He had to convince Congress to keep the money flowing, which was no small feat in the 1930s. He used a "pointing machine" to translate his small plaster models to the massive scale of the mountain. Imagine a giant protractor sitting on top of George Washington’s head. That’s basically what it was. For every inch on the model, the workers would measure out 12 inches on the mountain. It was precision engineering masked as art.

Lincoln Borglum: The Son Who Finished the Dream

We can't talk about the primary sculptors without mentioning Lincoln Borglum. He started as a teenager on the mountain, basically doing grunt work, but eventually became the superintendent. When his father died in March 1941—just months before the project was "finished"—Lincoln took over. Honestly, the mountain isn't even "done" in the way Gutzon envisioned. The original plan had the presidents carved down to their waists. But with World War II looming and the budget bone-dry, Lincoln called it a day. He saw the project through to its stopping point in October 1941.

The Real Muscle: 400 Miners and a Lot of Dynamite

Here is the part most people skip. If you ask a local in Keystone, South Dakota, who carved Mount Rushmore, they might give you a specific name of a grandfather or a great-uncle.

These men weren't sculptors. They were miners who were used to digging for gold in the Homestake Mine. Borglum hired them because they knew how to handle explosives and they weren't afraid of heights.

- The Powdermen: These guys were the rockstars. Literally. They used dynamite to blast away 90% of the rock. It wasn't delicate work. They would drill holes to specific depths and load them with small charges of dynamite to "skin" the mountain down to within a few inches of the final surface.

- The Drillers: Imagine sitting in a "bosun’s chair"—basically a wooden swing seat—dangling over a 500-foot drop. Now, pick up a 75-pound jackhammer. That was the daily life of a driller. They used "honeycombing" techniques, drilling holes close together so the remaining rock could be easily wedged off by hand.

- The Carvers: Once the heavy lifting was done, "bumpers" used small air-powered tools to smooth the surface. This is where the faces actually started to look like humans and not just jagged rocks.

It’s actually a miracle that nobody died during the 14 years of construction. Not one person. In an era where workplace safety was basically a suggestion, that’s an incredible stat. It speaks to the skill of the workers, even if they were working in clouds of silica dust that likely shortened many of their lives later on.

The Controversial Ground

It would be dishonest to talk about who carved Mount Rushmore without mentioning whose land it was. The Lakota Sioux call these mountains Paha Sapa. To them, the Black Hills are sacred, the center of the world. The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie technically gave this land to the Sioux forever.

Then gold was found.

The U.S. government took the land back, and decades later, Borglum showed up to carve the faces of four white men into a mountain the Indigenous people considered holy. This is why the Crazy Horse Memorial is being carved just a few miles away. It's a counter-narrative. When you stand at the viewing platform at Rushmore, you're looking at a feat of engineering, but also a site of deep, unresolved historical pain.

How They Actually Did It (Without Modern Tech)

You’ve got to appreciate the MacGyver-level ingenuity here. There were no computers. No lasers.

Basically, they built a small wooden house on top of each president’s head. Inside these "pentitentiaries," as they called them, was the master measurement system. A long boom swung out over the face, and a weighted line was dropped down to show the drillers exactly how deep to go.

If a driller went too deep? You can't put the rock back.

This happened on Jefferson. Originally, Jefferson was supposed to be on Washington’s right side. They carved for two years before realizing the quartz in the rock was too weak. They had to blast Jefferson’s face off—literally blow it up—and move him to the other side. That’s why the mountain looks a bit asymmetrical if you stare at it long enough.

✨ Don't miss: Boston I Had a Good Time: Why the City's New Vibe is Beating the Old Stereotypes

The Secret Room You Can't Visit

Borglum was a bit of a conspiracy theorist’s dream. He started carving a "Hall of Records" behind Lincoln’s head. He wanted it to be a massive vault containing the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. He envisioned a grand staircase and a massive bronze eagle over the door.

The government, predictably, hated the idea. They cut the funding. The Hall of Records exists today, but it’s just a 70-foot tunnel hacked into the granite. In 1998, they finally placed a small titanium vault in the floor of the entry containing porcelain tablets that explain why the mountain was carved, but for safety reasons, tourists aren't allowed anywhere near it.

The Logistics of 1927 to 1941

It cost $989,992.32 to build. In today’s money, that’s roughly $20 million. Honestly? That feels like a bargain.

The workers earned anywhere from $0.50 to $1.50 an hour. That sounds like pennies, but during the Depression, it was a lifeline. They climbed 700 stairs every morning just to get to work. There was no elevator until much later in the project. They carried their own heavy equipment. They worked in the scorching South Dakota sun and the brutal, wind-whipped winters until the cold made the rock too brittle to carve.

Actionable Insights for Your Visit

If you’re planning to go see the work of the men who carved Mount Rushmore, don’t just snap a selfie and leave. To really appreciate what happened there, you need a strategy.

1. Hit the Presidential Trail

Most people stay on the Grandview Terrace. Don't do that. Take the 422 stairs on the Presidential Trail. It gets you right up under the base of the mountain. From there, you can see the individual "honeycomb" marks and the actual texture of the granite. You can see the rubble pile at the bottom—over 450,000 tons of rock that they just let fall.

📖 Related: 4 person Eureka tents: Why they still dominate the campsite after 100 years

2. Visit the Sculptor’s Studio

This is where the 1:12 scale models are. Seeing the plaster faces that Borglum worked on makes the scale of the actual mountain feel even more impossible. You can see the "pointing" tools I mentioned earlier.

3. Go at Night

The lighting ceremony is a bit "touristy," sure, but seeing the faces emerge from total darkness is a different experience. It highlights the shadows and the depth of the carving in a way the midday sun flattens out.

4. Check Out Keystone

The town of Keystone was the hub for the workers. There are small local museums and markers that give you a better sense of the 400 families who actually lived through the construction.

5. Balance Your Perspective

Drive 30 minutes down the road to the Crazy Horse Memorial. It is still under construction (and has been since 1948). It provides the necessary context for the "other" side of the story regarding who carved Mount Rushmore and why the location remains so contested today.

The mountain is a paradox. It’s a masterpiece of engineering, a symbol of national pride, and a scar on a sacred landscape. It was built by a man with an ego the size of a mountain and 400 workers who were just trying to survive the 1930s. When you look up at those faces, you're seeing the result of 14 years of sweat, black powder, and a lot of grit.

To get the most out of your trip, try to arrive at the park before 9:00 AM. The morning light hits the faces directly, which is the best time for photography. If you wait until the afternoon, the sun moves behind the mountain, and the presidents end up in a giant shadow. Bring a windbreaker—even in July, the wind whipping off the granite can be surprisingly cold.