You’re probably holding a slab of glass and silicon right now that has more computing power than the entirety of NASA did when they put men on the moon. It’s sleek. It fits in your pocket. It’s basically an extra limb. But back in the early 70s, the idea of carrying a phone around was literally science fiction. If you wanted to make a call, you looked for a glass box on a street corner or sat at a desk. Then, one guy decided that shouldn't be the case.

When people ask who invented first cellular phone, the name that pops up—and rightfully so—is Martin Cooper. He was an engineer at Motorola, a company that, at the time, was a bit of an underdog compared to the giant that was AT&T. This wasn't just a "eureka" moment in a vacuum. It was a high-stakes, corporate arms race.

The Day Everything Changed

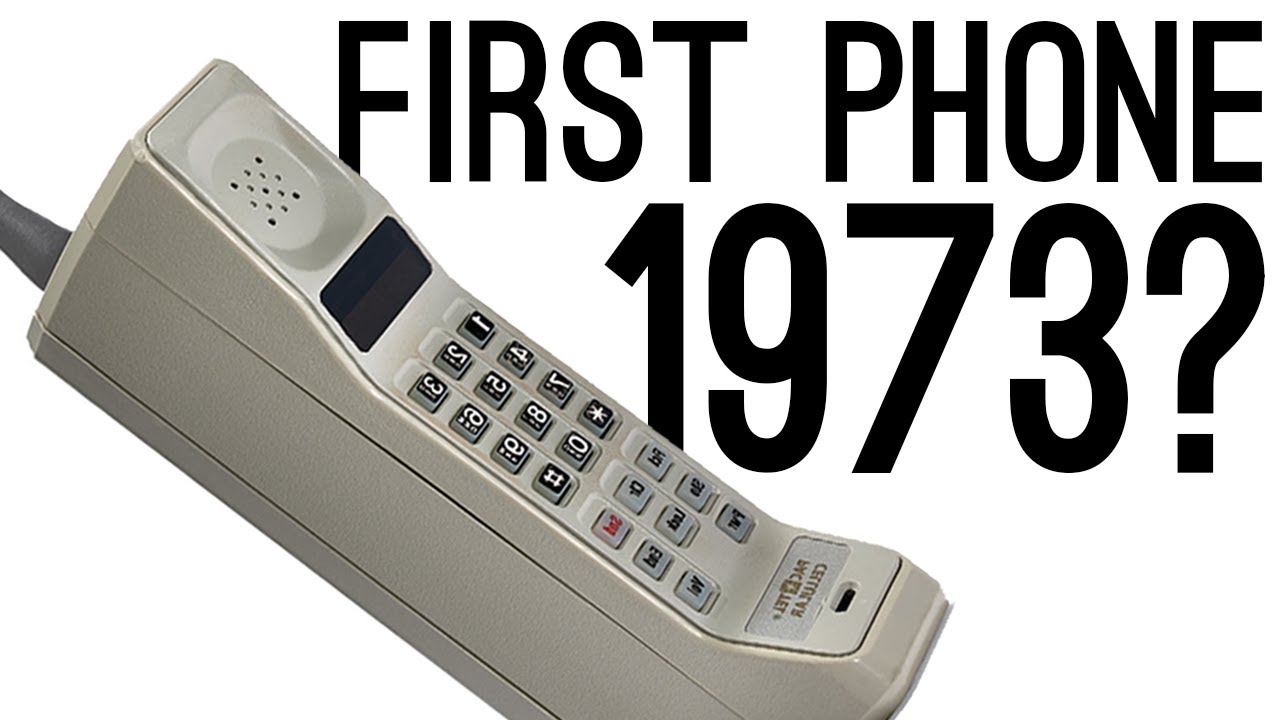

April 3, 1973. Imagine standing on Sixth Avenue in New York City. You see a man holding a device the size of a literal brick. It’s beige. It has a giant antenna. He isn't plugged into a wall. He’s walking and talking.

That man was Marty Cooper.

The most legendary part of this story isn't just the invention; it’s the sheer pettiness of the first call. Cooper didn't call his wife. He didn't call the president. He called Joel Engel. Engel was his rival over at Bell Labs (AT&T). Cooper basically said, "Joel, I’m calling you from a real cellular phone. A handheld, portable, real cellular phone."

Silence on the other end.

Cooper later joked that he could almost hear Engel grinding his teeth. It was the ultimate "mic drop" in the history of telecommunications. But the device Cooper was holding, the Motorola DynaTAC prototype, was a beast. It weighed about 2.5 pounds. You could talk for 20 minutes before the battery died, and then you’d have to charge it for ten hours. It was heavy. It was clunky. Honestly, it was glorious.

Why AT&T Almost Won (And Why They Lost)

It’s a common misconception that Motorola just "thought of it" first. In reality, AT&T’s Bell Labs actually came up with the concept of cellular technology back in 1947. D.H. Ring and others envisioned a system of "cells" that could reuse frequencies, which is the backbone of how your iPhone works today.

But AT&T had a specific vision. They thought the future was car phones.

They figured people would always be near a vehicle or a building. They didn't think individuals would want to carry a phone on their person. They wanted a monopoly on the infrastructure. Motorola, being much smaller, realized that if they didn't pivot to personal portability, they’d be crushed by AT&T’s sheer size. They bet the entire company on the idea that people want to talk to people, not places or cars.

🔗 Read more: Samsung is Chinese Company? Here is the Real Story

Marty Cooper led a team that built that first prototype in just 90 days. Think about that. Three months to change human history. They used parts from police radios and experimental components that barely worked.

The DynaTAC 8000X: From Prototype to Product

It took another decade for that 1973 prototype to become a commercial reality. Why? Because the FCC had to figure out how to allocate spectrum, and the technology had to be miniaturized enough to actually manufacture.

In 1983, the Motorola DynaTAC 8000X finally hit the market.

It cost $3,995.

Adjusted for inflation today? You’re looking at nearly $11,000. It was a status symbol for Wall Street "Gordon Gekko" types. It had a physical keypad, a red LED display, and weighed slightly less than the 1973 version, though not by much. People called it "The Brick." It didn't have apps. It didn't have text messaging. It just made calls. And yet, people lined up to buy it. It proved that the demand for being reachable anywhere was massive, even at a price tag that could buy a decent used car.

The Architecture of a Revolution

How did it actually work? Most people think the phone talks directly to another phone. Nope.

The "cellular" part of the name is the key. Cooper’s team had to figure out how to hand off a signal from one base station (a cell) to another without dropping the call as the user moved. This "handoff" is the secret sauce. Before this, "mobile" phones were basically powerful two-way radios. If you moved out of range of the one tower you were connected to, the call was dead.

Cooper’s team at Motorola—which included engineers like Rudy Krolopp, who headed the design—focused on the human element. Krolopp reportedly told his team that if the phone didn't look like something a human would actually want to hold, it didn't matter how well it worked. They looked at the shape of the human face. They curved the handset. They made it intuitive.

Common Myths About the First Cell Phone

A lot of folks get the timeline mixed up. Here are a few things that aren't quite right:

- Myth: Martin Cooper invented the first car phone. Wrong. Car phones existed since the 1940s. They were huge, heavy, and required a trunk full of equipment. Cooper’s breakthrough was portability.

- Myth: The first cell phone used a SIM card. Definitely not. Digital SIM cards didn't come around until the early 90s with the GSM standard. The original DynaTAC was analog. It used AMPS (Advanced Mobile Phone System), which was basically FM radio for your voice.

- Myth: Apple invented the smartphone. While the iPhone changed the interface, the first "smartphone" was actually the IBM Simon in 1992. It had a touchscreen and could send faxes.

The Legacy of the 1973 Call

Marty Cooper is still alive today, and he’s still incredibly sharp. He often speaks about how he’s disappointed that we spend so much time looking at our screens instead of talking to each other. He envisioned the phone as a tool for freedom.

When he stood on that sidewalk in Manhattan, he wasn't thinking about TikTok or Instagram. He was thinking about a world where you weren't tethered to a copper wire. He wanted to solve the problem of "where are you?" becoming a secondary question to "who are you?"

The engineering feat wasn't just the hardware; it was the audacity to challenge the biggest company in the world (AT&T) and prove their philosophy wrong. Motorola didn't have the resources Bell Labs had, but they had the vision of personal, untethered communication.

What You Should Do Next

If you’re a tech history buff or just curious about how we got here, there are a few ways to really "see" this history:

👉 See also: How Many GB in a TB: The Math Most People Get Wrong

- Check out the Smithsonian: The original DynaTAC prototype is often featured in their collections. It's a surreal experience to see how massive it is in person.

- Watch the 1973 Recreation: There are archival clips of Cooper talking about that first call. It’s worth a watch to see the genuine excitement he still has for the tech.

- Look at your own "Battery Health" settings: Next time you’re annoyed that your phone is at 10% after 12 hours, remember that the first cell phone gave you 20 minutes after 10 hours of charging. Perspective is everything.

- Read "Cutting the Cord": This is Martin Cooper’s book. He goes into the gritty details of the legal battles with the FCC and the internal struggles at Motorola.

Understanding who invented first cellular phone helps you appreciate the sheer complexity of the device in your hand. It wasn't a linear path. It was a messy, competitive, and expensive journey led by a man who just wanted to prove a point to his rival on a New York City street.