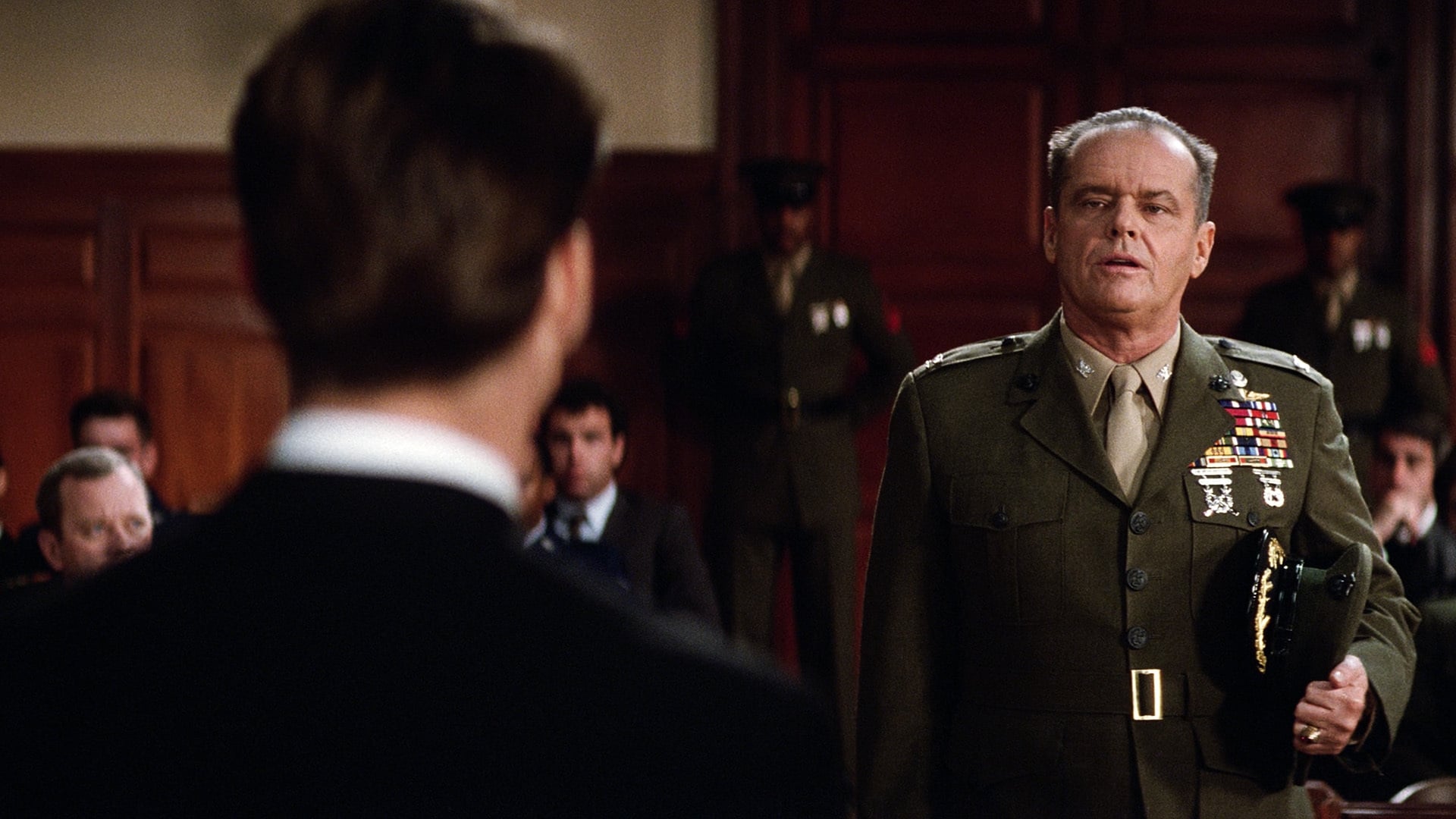

It is the lip twitch. Right before Jack Nicholson’s Colonel Nathan R. Jessep erupts into the most famous courtroom outburst in cinematic history, there is this tiny, involuntary movement of his face. He’s indignant. He’s powerful. He’s also about to be trapped. People remember A Few Good Men for the yelling, the "You can't handle the truth!" of it all, but the movie is actually a masterclass in slow-burn tension that most modern legal dramas just can't replicate.

Aaron Sorkin wrote the play based on a real-life phone call from his sister, Deborah, who was a JAG lawyer. She’d gone to Guantanamo Bay to defend a group of Marines who nearly killed a comrade in a hazing incident ordered by a superior. Sorkin took those bones and turned them into a script that feels like a rhythmic drumbeat.

Seriously.

The dialogue doesn't just happen; it bounces. It’s percussive. If you haven't seen it in a while, you forget how funny it is, too. Tom Cruise plays Lieutenant Daniel Kaffee as a lazy, Harvard-educated brat who just wants to play softball and settle cases without ever seeing the inside of a courtroom. He’s annoying. You’re supposed to find him annoying.

The Real Power of A Few Good Men is the Moral Grey

Most people think this is a movie about "good" lawyers vs. "bad" soldiers. That’s a massive oversimplification that ignores what makes the story actually work. The conflict isn't just about whether a crime was committed—we know the "Code Red" happened—it's about the justification of power in a high-stakes environment.

Jessep isn't a cartoon villain. In his mind, he is a pragmatist. He lives in a world where walls have to be guarded by men with guns, and he believes that the safety of the many outweighs the "weakness" of the one. This creates a genuine philosophical tension. When Jessep asks Kaffee, "Deep down in places you don't talk about at parties, you want me on that wall, you need me on that wall," he’s challenging the audience’s comfortable civilian life.

It's uncomfortable.

🔗 Read more: Why Role Model Kansas Anymore Is the Lyric That Defines Our Disillusionment

Rob Reiner, the director, understood that to make this work, the setting had to feel claustrophobic. Even the outdoor scenes at Gitmo feel hot, dusty, and restricted. You can almost smell the starch in the uniforms.

Why the Courtroom Scenes Rank Among the Best Ever

Legal dramas often fail because they get bogged down in technicalities that bore the audience. A Few Good Men avoids this by making the law feel like a weapon. Kaffee doesn't win by being a better person; he wins by being a better strategist. He goads Jessep. He uses the man’s own ego against him.

The strategy is actually grounded in real trial tactics. You don't ask a question you don't know the answer to, unless you're desperate. Kaffee was desperate.

There’s a specific moment during the cross-examination where the music stops. All you hear is the sound of the air conditioning and the shuffling of feet. That silence is more impactful than any swelling orchestral score. It forces you to focus on the faces of the actors. Kevin Pollak’s character, Sam Weinberg, is essentially the audience’s proxy—he’s the one who hates the defendants but loves the law. His skepticism throughout the movie makes the eventual victory feel earned rather than inevitable.

The Problem With the Code Red

A "Code Red" isn't a real military term in the official sense, but the concept of extrajudicial hazing or "corrective action" has a long, documented history in various military branches. The film explores the terrifying reality of "blind obedience."

Lance Corporal Dawson and Private Downey aren't monsters. They’re kids. They were told that their first duty was to the unit, then the Corps, then God, and then the Country. In that hierarchy, the order of a superior officer is absolute. The tragedy of the film isn't just Santiago’s death; it's the realization by Dawson at the end: "We were supposed to fight for people who couldn't fight for themselves."

🔗 Read more: Why Whitney Houston Songs Queen of the Night Redefined the Diva Persona

That line usually lands harder than the "Truth" speech for people who have actually served.

How the Movie Diverges from Sorkin’s Original Vision

In the original stage play, the ending is a bit more cynical. The Hollywood version gives us a triumphant Tom Cruise, but the play lingers longer on the fact that the two Marines still lost their careers. They were dishonorably discharged. They followed orders, and they still lost everything.

Reiner and Sorkin fought over several details during the adaptation. Interestingly, the character of JoAnne Galloway (played by Demi Moore) was originally supposed to have a romantic subplot with Kaffee. They filmed scenes that leaned into that, but ultimately realized it felt forced.

Good.

The movie is better because they didn't fall into the "male and female leads must kiss" trap. Their relationship is one of professional friction and mutual growth. She’s the conscience; he’s the talent. Without her pushing him, Kaffee would have stayed on the softball field, racking up easy plea bargains.

Technical Brilliance and the Nicholson Factor

Jack Nicholson was on set for only ten days. Ten.

Yet, his presence looms over every single frame of the film. He was paid $5 million for those ten days, which was a massive sum in 1992. But look at what he did with it. He gave the same high-intensity performance during the off-camera lines for the other actors as he did when the lens was on him. That’s rare.

When you watch A Few Good Men, pay attention to the editing by Robert Leighton. The way it cuts between the crisp, high-contrast shots of Washington D.C. and the hazy, oppressive atmosphere of Cuba creates a visual shorthand for the "two worlds" Jessep talks about. One world lives in the light of the law; the other lives in the shadows of "security."

📖 Related: House of Hannah Montana: Why the Iconic Malibu Beach House Still Matters

The film also benefits from a supporting cast that is frankly absurdly good.

- James Marshall as the quiet, terrified Downey.

- Kiefer Sutherland as the zealot Kendrick (who is arguably scarier than Jessep because he actually believes his own religious rhetoric).

- J.T. Walsh as Markinson, the man caught in the middle who represents the "good" officer who waited too long to speak up.

Walsh’s performance is heartbreaking. His character’s suicide is the turning point that raises the stakes from a legal battle to a matter of life and death. It’s the moment Kaffee realizes that Jessep isn't just a bully—he’s a predator.

Common Misconceptions About the Legal Accuracy

Is it a 100% accurate representation of a Court Martial? No.

Real JAG officers often point out that Kaffee’s courtroom theatrics would have had him held in contempt almost immediately. The "discovery" process in military law also wouldn't usually allow for the kind of "surprise" witnesses we see in movies.

However, the film gets the spirit of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) right. It captures the tension between the Bill of Rights and the necessity of a disciplined fighting force. You can’t have a democracy without an army, but you can’t have an army that operates entirely outside the values of that democracy. That’s the paradox at the heart of the story.

Actionable Takeaways for Your Next Rewatch

To get the most out of A Few Good Men today, try looking past the memes.

- Watch the background characters. During the courtroom scenes, the reactions of the jury and the gallery tell a story of their own. You can see the moment the tide shifts just by watching the bailiff.

- Listen for the "Sorkinisms." This was one of the first times the world heard his signature "walk and talk" style. Notice how the dialogue speeds up as the characters get closer to the truth.

- Analyze the lighting on Jessep. In his final scene, he starts in the shadows and moves into the light as he gets more arrogant. By the time he confesses, he’s fully exposed, literally and figuratively.

- Compare it to "The Caine Mutiny." If you like this film, go back and watch the 1954 classic. You’ll see where Sorkin got a lot of his inspiration for the "officer on the edge" archetype.

The movie holds up because it doesn't provide easy answers. It asks if we are willing to accept the cost of our safety. It asks if "following orders" is a valid excuse for losing your humanity. Most importantly, it reminds us that the truth usually doesn't come out because someone wants to tell it; it comes out because someone else is smart enough to corner it.

Go watch it again. Focus on the quiet scenes between Kaffee and his father’s legacy. It's a movie about a son trying to prove he’s worth the name he carries, and that’s a story that never gets old.

Next Steps for Film Enthusiasts:

- Research the real-life case of William Alvarado, the Marine whose experience inspired Sorkin’s sister to tell the story.

- Compare the 1992 film with the 2018 live television production to see how the staging changes the impact of the dialogue.

- Check out the "Screenplays" section of your local library to read Sorkin's original script; seeing the words on the page reveals the rhythmic "musical" structure of the scenes.