You’ve seen it on every schoolroom globe. A massive, beige blob taking up the top third of Africa. It looks static. It looks like a giant, empty sandbox. But if you actually try to look at a map of Sahara Desert today, you’ll realize that most of our mental images are basically wrong.

The Sahara isn’t just one thing. It's a shifting, living beast. It’s actually bigger than the contiguous United States. Think about that for a second. You could fit all 48 lower states inside this "wasteland" and still have room to spare. Yet, we treat it like a single destination on a map.

👉 See also: Weather in Seattle WA Explained: Why Everything You Know Is Kinda Wrong

The Borders Are Honestly Just a Suggestion

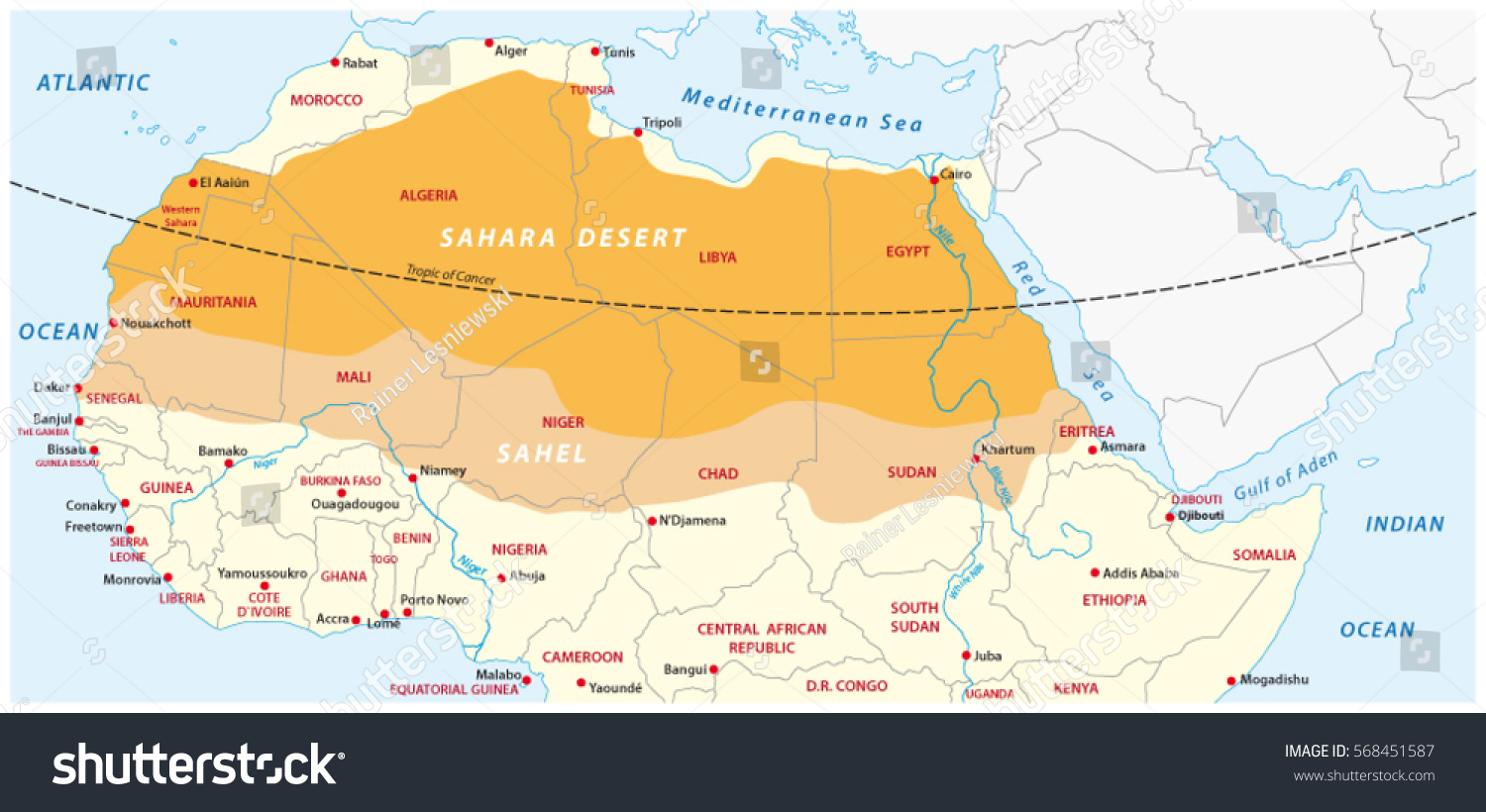

If you look at a political map of Sahara Desert, you’ll see crisp lines cutting through the sand. You’ve got Algeria, Chad, Egypt, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Sudan, and Tunisia. Eleven countries in total if you count the disputed territory of Western Sahara. But the desert doesn't care about passports.

The "Green Sahara" cycles are a real thing that geologists like Stefan Kröpelin have spent decades studying. Every 20,000 years or so, the Earth’s wobble changes the monsoon patterns. This means the map you see today is just a temporary snapshot. A few thousand years ago, this was a lush land of hippos and giraffes. Today? It’s expanding. The Sahara has grown by about 10% since 1920. It's pushing south into the Sahel, swallowing villages and changing the map of Africa in real-time.

People think it's all sand dunes. It isn't.

Actually, ergs—the giant sand seas everyone recognizes from movies—only make up about 25% of the desert. The rest? It’s hamada (barren, rocky plateaus), reg (plains of coarse gravel), and salt flats. If you were to walk across a "map" of the Sahara, you’d spend way more time twisting your ankle on sharp rocks than sliding down soft sand.

Mapping the Highs and Lows

Geography is weird. Most people assume the desert is flat. It’s not.

Look at the Tibesti Mountains in Chad. You’ve got Emi Koussi, a shield volcano that hits 3,415 meters (over 11,000 feet). It literally gets snow sometimes. Imagine that. Snow in the middle of the world’s most famous hot desert. On the flip side, you have the Qattara Depression in Egypt. It’s 133 meters below sea level.

It’s a landscape of extremes that most digital maps fail to capture. When you use Google Earth to zoom in on the map of Sahara Desert, you start seeing these incredible "eye" structures, like the Richat Structure in Mauritania. It looks like a giant bullseye from space. For a long time, people thought it was a meteor crater. Now, scientists believe it’s a deeply eroded geological dome.

Why Satellites Struggle Here

Mapping this place is a nightmare. Sand moves.

One day a dune is in one spot; a week later, after a "khamsin" or "harmattan" wind storm, the topography has literally changed. This makes traditional land surveying almost impossible in the deep interior. Cartographers have to rely on radar imaging that can see through the sand to the ancient, dried-up riverbeds (paleodrainage systems) underneath. These hidden rivers are the reason why oases exist.

The Human Map: Trade and Survival

The Sahara has never been empty.

Historically, it was crisscrossed by salt and gold trade routes. If you look at an old 14th-century map of Sahara Desert, like the Catalan Atlas, it shows Mansa Musa—the richest man in history—holding a gold coin in the middle of the desert. The map wasn't about sand; it was about wells.

Today, the "human map" is defined by:

- The Trans-Sahara Highway: A massive project trying to pave a route from Algiers to Lagos.

- Tuareg and Berber territories: Groups who have navigated these dunes for millennia without a GPS.

- Oil and Gas fields: Huge pockets in Algeria and Libya that drive the modern economy but are often blurred out or restricted on public maps.

Water is the ultimate currency. If you aren't looking at the locations of the aquifers—like the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System—you aren't looking at a useful map. This underground "fossil water" is what keeps places like the Kufra Oasis in Libya green enough to be seen from the moon.

What Most Maps Get Wrong About the Climate

It’s not just "hot."

In the winter, temperatures in the highlands can drop to -18°C (0°F). It’s a "cold" desert that happens to get incredibly hot during the day. This thermal swing is what cracks the rocks and turns mountains into gravel over millions of years.

🔗 Read more: Has Gulf of Mexico Been Renamed? The Truth Behind the Viral Rumors

Also, the Sahara isn't the largest desert in the world.

Antarctica is.

The Sahara is the largest hot desert.

When you look at the map of Sahara Desert, you should also look at the dust. Sahara dust travels across the Atlantic Ocean. It fertilizes the Amazon rainforest and provides the minerals needed for Caribbean beaches. The map of the Sahara's influence actually extends thousands of miles beyond its physical borders.

Actionable Insights for Navigating or Studying the Sahara

If you’re planning to travel to the fringes or just want to understand the geography better, keep these points in mind:

- Don't rely on standard GPS: In the deep desert, landmarks move. Professional expeditions use satellite phones and high-resolution topographic maps that identify "sebkhas" (salt pans) which can be dangerous for vehicles.

- Watch the Sahel: If you're interested in ecology, look at the "Great Green Wall" project. It's a cross-continental effort to plant a strip of trees to stop the Sahara's southern expansion.

- Use Radar Imagery: If you're a geography nerd, check out NASA’s Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) data. It reveals the "ghost geography" of the Sahara—ancient lakes and river valleys buried under the sand.

- Check Political Stability: A map of Sahara Desert is also a map of complex geopolitics. Always cross-reference your travel plans with updated "no-go zone" maps from state departments, as border regions in Mali and Libya can change status overnight.

The desert is growing, it's breathing, and it's far more than just a blank space on the map. Understanding its true scale and diversity is the first step to respecting one of the most intense environments on our planet.