We’ve all been there. You’re looking at a map with state names and suddenly realize you have no earthly idea where Arkansas actually sits. Is it bordering Mississippi? Does it touch Missouri? It’s embarrassing. Honestly, even for people who pride themselves on being geography nerds, the mental image of the U.S. is usually a blurry mess once you move away from the coasts.

Geography is weird.

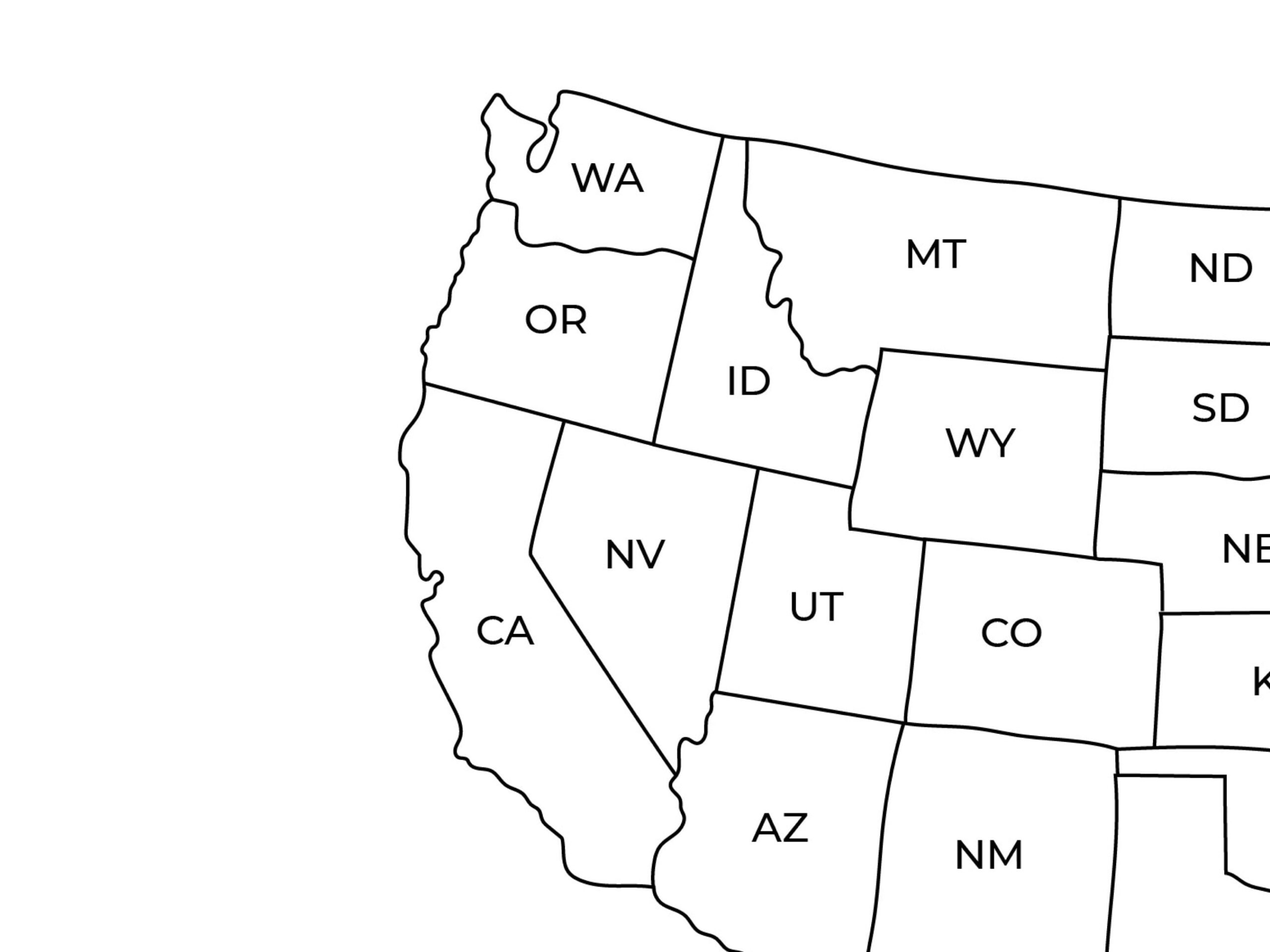

It’s not just about knowing where things are located; it’s about how we visualize space. Most of us grew up staring at those pull-down maps in elementary school, the ones with the faded pastels and the weirdly thick borders. But the moment you strip those names away, the "rectangular" states in the West start looking identical. Wyoming? Colorado? Good luck.

The Mental Map vs. The Real Map

There is a massive gap between what we think the country looks like and what a literal map with state names shows us. Take the "vertical alignment" of the East Coast. Most people assume that if you drive straight south from Detroit, you’ll stay in the Midwest or hit the South. You actually end up in Canada if you go the wrong way, or way further east than you’d expect.

💡 You might also like: Gumbo Collard Greens Recipe: Why This Mashup Is Better Than The Original

The cognitive load of memorizing fifty distinct shapes is high. That's why we rely on labels. Without them, the "M" in the "MIMAL" man (that mnemonic device where Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas, and Louisiana look like a chef) just becomes a series of jagged lines. People often forget that the United States is roughly the size of Europe. Imagine trying to name every European country on a blank slate. It’s a nightmare.

Digital mapping has made us lazier, too. You’ve probably noticed that when you open Google Maps, you aren't looking at a map with state names primarily; you're looking at blue lines and ETA markers. We’ve traded spatial awareness for turn-by-turn instructions. This shift has actually degraded our ability to "see" the country as a cohesive unit. We see it as a series of points and connections rather than a jigsaw puzzle of jurisdictions.

Why Border Disputes Still Matter in 2026

You’d think the borders on a map with state names were settled centuries ago. Wrong. They are surprisingly fluid, or at least, surprisingly contested.

Take the "Battle of the 35th Parallel." For years, Georgia and Tennessee have been in a low-key spat over a tiny sliver of land. Why? Water rights. If the border moved just a few hundred feet north—where it was originally supposed to be according to an 1818 survey error—Georgia would have access to the Tennessee River. Georgia's legislature has actually passed resolutions to "correct" this. Tennessee, unsurprisingly, told them to kick rocks.

Then there’s the "Kentucky Bend." If you look at a detailed map with state names, you’ll see a tiny piece of Kentucky that is completely detached from the rest of the state, surrounded by Missouri and Tennessee. It’s an exclave created by the New Madrid earthquakes in the early 1800s, which actually made the Mississippi River flow backward for a while.

- Surveying errors in the 1700s created "wedges" and "notches" that still exist today.

- Rivers change course, leaving farmers in one state suddenly owning land in another.

- Tax implications often drive modern movements to redraw state lines, like the "Greater Idaho" proposal where parts of eastern Oregon want to secede and join their neighbor.

The Design Evolution of the American Map

The way we display a map with state names has changed from hand-drawn vellum to 4K Retina displays. Early maps were propaganda. They were designed to make the colonies look bigger, more inviting, and more organized than they actually were.

Cartographers like John Mitchell, whose 1755 map was used to establish the boundaries of the U.S. after the Revolutionary War, were working with limited data. His map was riddled with errors, yet it became the legal standard. We are literally living within the mistakes of 18th-century illustrators.

Modern maps use the Mercator projection mostly because it fits nicely on a phone screen, but it distorts the size of states. Texas looks massive (and it is), but the way the projection stretches toward the poles makes northern states look relatively larger than they are compared to those near the equator. If you look at a map with state names using a Gall-Peters projection, the whole country looks "stretched" and "skinny," which is technically more accurate regarding land mass but feels "wrong" to our conditioned brains.

Practical Ways to Actually Learn Your Geography

Stop using GPS for a day. Seriously. If you want to stop feeling like a tourist in your own country, you have to engage with the map with state names actively.

- Print a physical map. Stick it on the back of your bathroom door. It sounds 1994, but passive consumption works.

- Play "The Shape Game." Try to identify states based solely on their outline. You'll realize how much you rely on the Great Lakes or the coastline to orient yourself.

- Learn the "Anchor States." Don't try to memorize all 50. Learn the corners and the "spine" (the Mississippi River). Once you know the anchors, the rest of the puzzle pieces fall into place.

The 2020 census and subsequent redistricting also shifted how we perceive these borders. While state lines didn't move, the "weight" of the names did. Some states gained congressional seats; others lost them. This changed the political map with state names, turning "flyover country" into "battleground territory" in the eyes of the media.

Misconceptions About the "Four Corners"

Everyone loves the idea of the Four Corners. You can stand in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah all at once. It’s a bucket-list item for road trippers.

But here’s the kicker: it’s technically in the wrong spot.

Due to the primitive surveying tools available in the 1860s and 1870s, the actual monument is about 1,800 feet east of where it was legally intended to be. However, the Supreme Court has basically ruled that even if a survey is wrong, once it’s established and accepted, that is the boundary. Accuracy takes a backseat to tradition. When you look at a map with state names, you’re looking at a history of "close enough."

Actionable Insights for the Geography-Minded

If you’re looking to master the U.S. map or use it for a project, keep these tips in mind:

- Check the projection. If you’re comparing the size of California to the size of Florida, ensure you aren't using a projection that distorts the ends of the map.

- Verify the date. Maps from before 1959 don't include Hawaii and Alaska as states. Maps from the early 1800s have "Territories" that look nothing like the modern West.

- Look for the "Panhandles." States like Oklahoma, Florida, and West Virginia have distinctive panhandles that serve as great visual landmarks when scanning a labeled map.

- Use topographic overlays. A map with state names is more interesting when you see why the borders are there. Many follow ridgelines of the Appalachians or the winding paths of major rivers.

Start by finding a high-resolution PDF or a physical wall map that includes both state names and major topographical features. Spend five minutes a week tracing the border of a state you’ve never visited. You’ll find that the "boring" middle of the country has some of the most complex and bizarre border stories in the world. Understanding the map is about understanding the messy, human history of how we claimed the land.