You’ve probably seen it in a biology textbook. That little lumpy, snowman-shaped blob floating in a sea of blue cellular fluid. When you look at a picture of a ribosomes, it usually looks like a couple of disorganized beans stuck together. Honestly? It’s kind of a mess. But that messy little blob is the only reason you are currently breathing, thinking, and reading this sentence.

Ribosomes are the blue-collar workers of the cell. They don't get the glory of the nucleus (the "brain") or the mitochondria (the "powerhouse"). They just sit there. They translate. They build. Without them, your DNA is just a useless instruction manual for a furniture set that never gets built.

What You’re Actually Seeing in a Picture of a Ribosomes

When you search for an image of these things, you aren't seeing a photo in the traditional sense. You can’t just point a Kodak at a cell and click. Ribosomes are tiny. Like, 20 to 30 nanometers tiny. For context, a human hair is about 80,000 nanometers wide.

Most of what we call a picture of a ribosomes is actually a 3D model based on something called cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). This tech is wild. Scientists flash-freeze samples so fast that water doesn't even have time to form crystals. Then they blast it with electrons to map out the structure. The result is a high-resolution map of atoms.

The Large and Small Subunits

Usually, the image shows two distinct parts. Scientists, being the creative types they are, call these the "Large Subunit" and the "Small Subunit."

The small one (40S in humans) is like the reader. It grabs the mRNA—the "code" sent from your DNA—and holds it steady. The large one (60S) is the heavy lifter. It’s responsible for actually bonding amino acids together to form a protein chain. Think of it like a 3D printer where the bottom half feeds the plastic and the top half melts it into shape.

The "Blob" vs. The Reality

If you look at older diagrams from the 90s, ribosomes look like smooth potatoes. They’re beige. They’re boring. Modern images, especially those coming out of labs like the Ramakrishnan Group, show a tangled jungle of RNA and proteins.

It’s mostly RNA.

That’s the weird part. We used to think proteins did all the work in the body, but ribosomes prove that RNA—the "messenger" molecule—is actually the engine. About 60% of a ribosome's mass is ribosomal RNA (rRNA). The proteins are just there to hold the RNA scaffolding in place. It's an "RNA World" artifact that survived billions of years of evolution.

Where They Hang Out

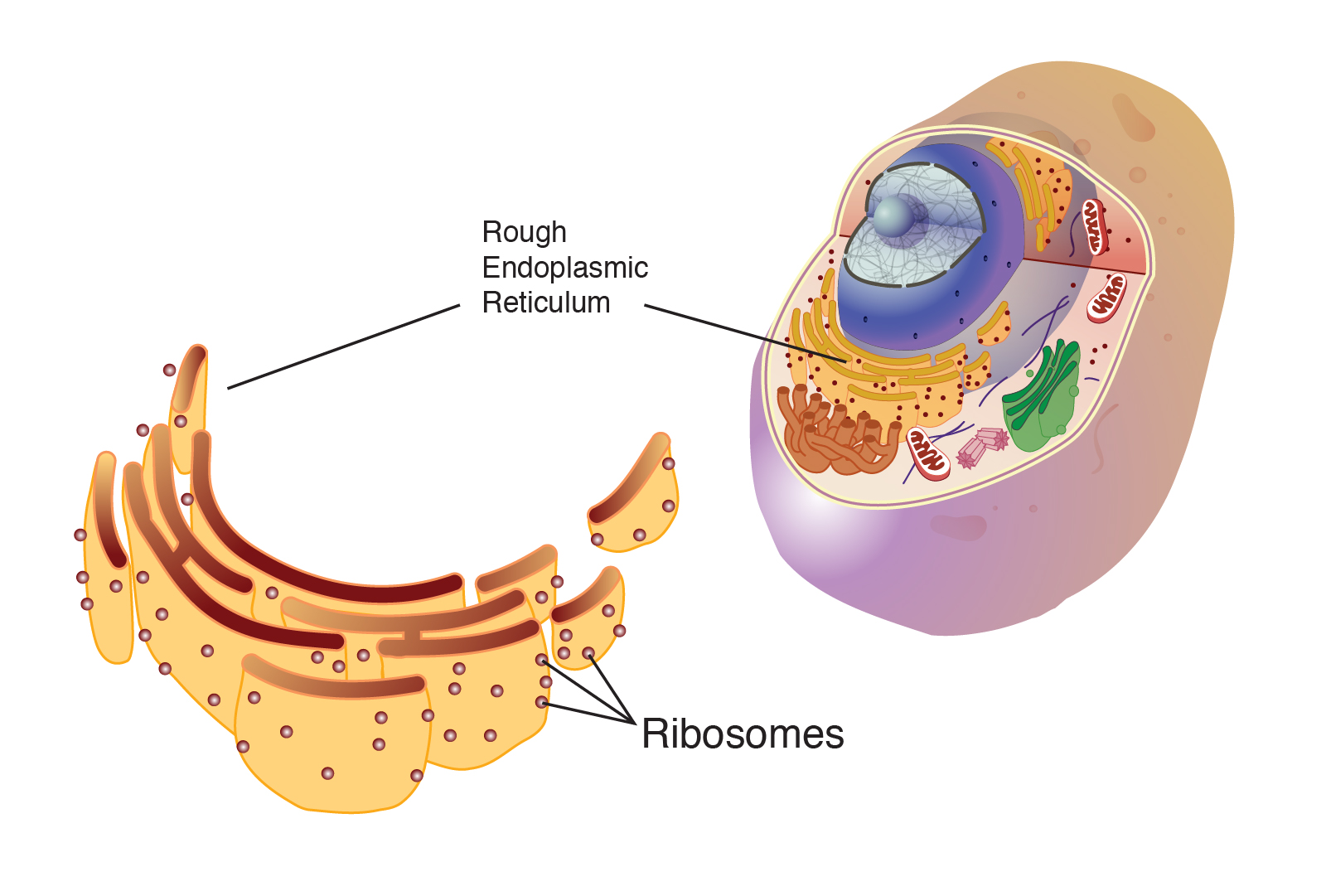

A picture of a ribosomes often shows them stuck to a giant, wavy structure called the Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER). It looks like a stack of pancakes covered in sprinkles. Those "sprinkles" are the ribosomes.

- Ribosomes on the ER make proteins that leave the cell (like insulin).

- "Free" ribosomes floating in the cytoplasm make proteins for use inside the cell.

If you see a picture where they are just scattered like dust, those are the free-floating ones. They’re identical in structure, just different in their "commute" to work.

Why Your Doctor Cares About This Structure

This isn't just for academic nerds. The specific shape shown in a picture of a ribosomes is the reason you can survive a bacterial infection.

Bacteria have ribosomes too. But their ribosomes (70S) are shaped differently than ours (80S). They’re slightly smaller and have different nooks and crannies.

Antibiotics like tetracycline or erythromycin are basically microscopic monkey wrenches. They are shaped specifically to fit into the bacterial ribosome's "slots" but not yours. They jam the machinery. The bacteria can't make proteins, it can't reproduce, and it dies. Meanwhile, your human ribosomes keep humming along because the "wrench" doesn't fit their shape.

✨ Don't miss: Rite Aid Pharmacy Monroe WA: What Most People Get Wrong About This Local Hub

Common Misconceptions in Visuals

People often think ribosomes are "alive" or that they move like little robots with legs. They don't. They operate on pure chemistry and thermal energy. They jiggle around until the right molecule happens to bump into them. It’s a chaotic, high-speed bumper car match.

Another mistake? Thinking they last forever. Your cells are constantly recycling them. If a ribosome breaks or stalls, the cell has quality-control systems (like the No-Go Decay pathway) that come in, tear the ribosome apart, and recycle the parts.

How to Read a Ribosome Map

If you’re looking at a professional-grade scientific picture of a ribosomes, you’ll see three distinct "sites" labeled A, P, and E.

- The A site (Aminoacyl): This is the "Entry" gate. New amino acids arrive here.

- The P site (Peptidyl): This is the "Processing" center. This is where the growing protein chain lives.

- The E site (Exit): This is the "Eject" button. Once the tRNA has dropped off its cargo, it gets kicked out here.

It’s a literal assembly line. Every single protein in your body—from the collagen in your skin to the hemoglobin carrying oxygen in your blood—passed through these three gates.

The Future of Imaging

We are moving past static images. The next step in cellular photography is "in situ" imaging. Instead of taking the ribosome out of the cell to look at it, scientists are using cryo-electron tomography to take a picture of a ribosomes while it’s still inside a living, functioning cell.

This reveals that they aren't just floating randomly. They often form "polysomes," which look like beads on a string. Multiple ribosomes will hop onto a single strand of mRNA at the same time, cranking out dozens of copies of a protein simultaneously. It’s mass production at the molecular level.

Actionable Insights for Biology Students and Enthusiasts

When studying these structures, don't just memorize the "snowman" shape. Focus on the functional geometry.

First, identify the source of the image. Is it a stylized textbook illustration or a cryo-EM density map? The density maps (usually colorful and lumpy) show the actual atomic placement, while illustrations (smooth and geometric) are better for understanding the A-P-E workflow.

Second, look for the mRNA "tether." A ribosome is rarely just sitting there; it’s almost always attached to a thin line of genetic code. If you see a picture of a ribosomes without mRNA, you're looking at an inactive state.

Finally, remember the scale. The sheer number of these things is staggering. A single human liver cell contains about 13 million ribosomes. If you could zoom in on your own body right now, you’d see trillions of these machines working in total silence, building the "you" that exists five minutes from now.

To truly understand cellular health, you have to appreciate the ribosome as a physical object—a machine with moving parts, entry ports, and an exhaust pipe. It is the bridge between the digital code of DNA and the physical reality of your body.