You’re probably used to being sold things 24/7. It’s the air we breathe. But if you could time travel back to the early 1900s, you’d realize that people didn't actually "consume" things the way we do now. They bought what they needed. Then the decade of the flapper and the Jazz Age hit, and advertisement from the 1920s basically rewired the human brain to want things they didn't even know existed five minutes prior.

It wasn't just about pretty posters.

The 1920s marked a violent shift from "here is a sturdy rug" to "your neighbors will think you’re a failure if your rug is dusty." It was the birth of the modern identity crisis as a sales tactic.

The Fear Factor: How Halitosis Changed Everything

Before 1920, if you had bad breath, you just had bad breath. Maybe you chewed some parsley. But then came Gerard Lambert and the team behind Listerine. They didn't just sell mouthwash; they sold a social nightmare. They dug up an obscure medical term—halitosis—and turned it into a "silent" social killer.

Honestly, it was genius. And kind of evil.

✨ Don't miss: Who was the founder of Nike? The real story of Blue Ribbon Sports

The ads featured "Edna," a beautiful woman who was "often a bridesmaid but never a bride." Why? Because she had halitosis. She didn't know it. Her friends wouldn't tell her. The stakes weren't just dental hygiene; the stakes were your entire future and romantic happiness. By 1928, Listerine's profits had climbed from roughly $100,000 to over $4 million annually. They proved that advertisement from the 1920s worked best when it preyed on the universal human fear of being an outsider.

This was the "reason-why" advertising era on steroids.

Claude Hopkins, one of the legendary figures at Lord & Thomas, was a big believer in this. He didn't think people bought things for fun. He thought they bought things to solve a problem or gain an advantage. When he took on Pepsodent, he didn't talk about health. He talked about "the film" on teeth. He created a trigger: feel your teeth with your tongue, notice the film, use Pepsodent to remove it. He turned brushing into a daily habit by creating a craving for that tingly, clean feeling.

When Radio Killed the Print Star (Kinda)

Radio was the Wild West. In the early 20s, people weren't even sure if it was ethical to advertise on the airwaves. It felt like an intrusion into the home.

Herbert Hoover, who was Secretary of Commerce at the time, actually said, "It is inconceivable that we should allow so great a possibility for service to be drowned in advertising chatter." He was wrong. Very wrong.

By 1926, the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) was formed, and the gold rush was on. But the format was weird. You couldn't just play a 30-second spot. Instead, brands sponsored entire hours. This gave us the "Evereadys" or the "A&P Gypsies." You'd listen to a full orchestra, but the name of the brand was baked into the identity of the performers.

It was the first version of "native advertising."

If you were a housewife in 1924, you weren't just hearing a commercial; you were inviting a brand spokesperson into your kitchen. This created a level of intimacy that a newspaper ad could never touch. It made brands feel like friends. That’s a trick companies are still trying to pull off on TikTok today, and they’re basically just using the 1920s playbook with better cameras.

The Rise of the Brand Personality

Look at the "Betty Crocker" phenomenon. Betty isn't real. She never was. She was created by the Washburn-Crosby Company (which became General Mills) in 1921 because they were getting too many letters from customers asking for baking advice. They needed a face. A motherly, expert figure who could sign the letters.

It worked so well that Betty Crocker eventually got her own radio show, The Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air. People trusted her. They felt a connection to a fictional character, which is exactly what happens now when people get "attached" to a brand's Twitter persona.

Buying on the "Never-Never"

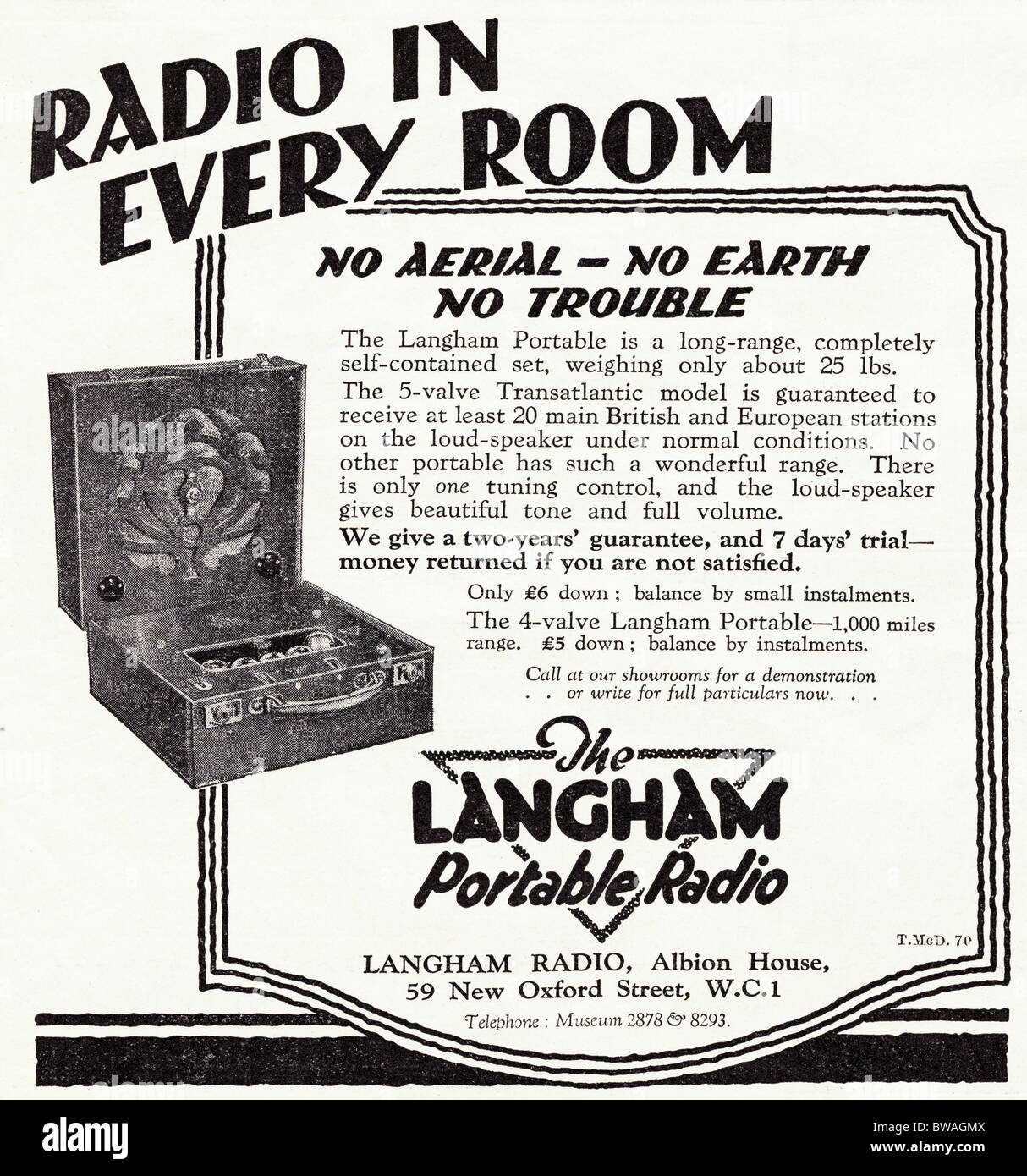

You can't talk about advertisement from the 1920s without talking about credit. Or "installment buying," as they called it.

Before the 20s, if you couldn't afford a car, you didn't buy a car. Simple. But then productivity exploded. Factories were pumping out Model Ts and washing machines faster than people could save up cash to buy them. The solution? Sell the dream of ownership for five dollars a month.

General Motors Acceptance Corp (GMAC) was a pioneer here. Their ads stopped focusing on the engine and started focusing on the lifestyle. "Drive it home today." The copy focused on the freedom of the open road and the status of the shiny chassis.

- In 1920, few middle-class families had significant debt.

- By 1929, 60% of cars and 80% of radios were bought on the installment plan.

- The ads made debt look like a smart financial move for the modern family.

It was a total psychological shift. Advertisement didn't just sell the product; it sold the permission to spend money you hadn't earned yet.

🔗 Read more: Why Time Work Plus Employee Management is Failing Small Businesses (And How to Fix It)

Gender Roles and the "New Woman"

The 19th Amendment passed in 1920. Women had the vote, and more importantly for Madison Avenue, they had more agency. Advertisers went into overdrive trying to figure out the "New Woman."

They marketed cigarettes as "Torches of Freedom." This was a famous campaign by Edward Bernays—the nephew of Sigmund Freud, by the way—for the American Tobacco Company. He realized that if he could link Lucky Strikes to the women’s rights movement, he’d double his market overnight. He literally hired women to march in the 1929 Easter Sunday Parade in New York while smoking.

It was a PR stunt that changed social norms forever.

But it wasn't all "liberation." A lot of advertisement from the 1920s was incredibly regressive. While one ad told a woman she could be a flapper, three others told her she was failing as a mother if she didn't use a specific brand of canned soup or a Hoover vacuum. The "scientific" mothering movement was huge. Ads would quote "doctors" (who were often just actors or generic illustrations) claiming that your child's health depended entirely on whether you bought a certain brand of cereal.

It created a high-pressure environment for women. You were expected to be modern, stylish, and free, but also a domestic scientist with a spotless kitchen.

The Visual Revolution: Art Deco and Psychology

The look of ads changed too. In the 1910s, ads were text-heavy and boring. By the mid-20s, the Art Deco movement was in full swing. Everything looked sleek, geometric, and expensive.

J. Walter Thompson, one of the powerhouse agencies, started hiring actual psychologists. They wanted to know why people clicked—or, in those days, why they clipped coupons. They used the "AIDA" model: Attention, Interest, Desire, Action.

📖 Related: 180.00 pesos to dollars: Why that small change tells a bigger story about your money

Desire was the big one.

They started using "soft sell" techniques. Instead of listing the features of a Cadillac, they’d show a painting of a Cadillac parked outside a grand opera house. No price. No engine specs. Just the implication that if you owned this car, you belonged in that world.

Lessons We Can Still Use

So, why does any of this matter now? Because we’re still living in the world they built. If you’re a business owner or a creator, the 1920s taught us three massive things that haven't changed:

- Solve a "Hidden" Problem: Don't just sell a product. Sell the solution to a social or emotional anxiety the customer didn't realize they had.

- Build a Character: People don't trust corporations. They trust people (even fictional ones like Betty Crocker). Give your brand a voice that sounds human.

- Sell the Lifestyle, Not the Spec Sheet: Features tell, but benefits—and emotions—sell. Show what the product makes the user become.

The advertisement from the 1920s was the first time we saw the "aspirational" life used as a weapon of commerce. It’s the reason you feel a little bit better when you buy a certain brand of sneakers or a specific phone. It’s not just a tool; it’s a piece of who you are.

If you want to understand modern marketing, stop looking at what happened last week on Instagram and start looking at what happened in a smoky office in New York a hundred years ago. The tools are different, but the people? We're exactly the same. We still want to belong, we’re still afraid of "halitosis," and we’re still looking for a way to buy the life we want on the "never-never."

To truly apply these historical insights to a modern business strategy, start by auditing your current messaging. Look for where you are being "informative" when you should be "emotive." Replace technical jargon with a narrative that places the customer as the hero of a story—much like the Pepsodent ads did for the everyday worker. Finally, identify the "silent" anxieties in your niche and address them directly, offering your product not just as a commodity, but as a necessary relief from social or professional friction.