Ray Stevens is a weird dude. Not in a bad way, necessarily, but in that "how did he get away with this for fifty years" kind of way. If you grew up in the 60s or 70s, or if you spent any time digging through your parents’ vinyl collection, you’ve run into him. He’s the guy who gave us "The Streak" and "Everything is Beautiful." But long before he was winning Grammys for pop anthems, he dropped a novelty record in 1962 that basically defined the early era of his career. That song was Ahab the Arab.

It’s a bizarre piece of audio. You’ve got the fake Middle Eastern flute lines, the gibberish chanting, and Stevens doing a high-pitched, warbling caricature of a voice. It hit number five on the Billboard Hot 100. People loved it. Today? It’s a polarizing artifact that makes music historians sweat and modern listeners tilt their heads in confusion.

The Wild Origin Story of a 1962 Mega-Hit

Ray Stevens didn't just stumble into the studio and accidentally record a hit. He was a savvy songwriter who understood the power of a gimmick. In 1962, novelty songs were a massive business. Think about it. This was the era of "The Chipmunk Song" and "Monster Mash." Listeners wanted to laugh. Stevens, who was working out of Nashville, saw an opening for a character-driven narrative that utilized the "exotic" sounds that were popular in mid-century lounge music.

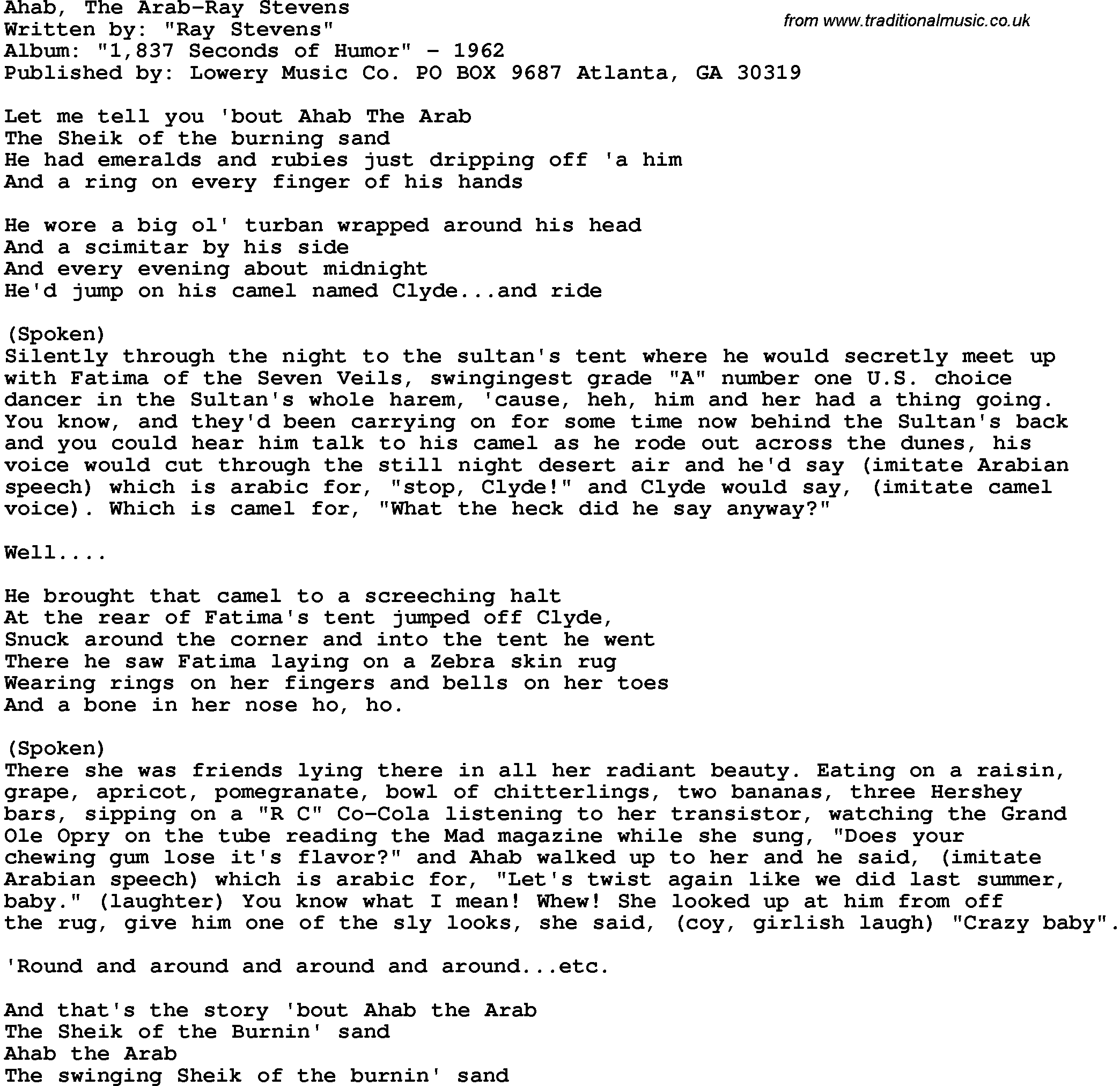

He recorded the song for Mercury Records. The premise is simple: Ahab is a "sheik of the burning sands" who hops on his camel, Clyde, to visit his secret girlfriend, Fatima, in her tent.

The recording process itself was pure DIY ingenuity. Stevens did almost all the voices himself. That iconic "Ahab!" shout? That’s Ray. The weird, trilling vocalizations that sound like a mix between a bird call and a Yodel? Also Ray. He used a lot of slapback echo and reverb to create a sense of scale, making a tiny Nashville studio sound like a vast, cinematic desert. It was technically impressive for the time, even if the subject matter was, let's say, a bit narrow-minded.

What’s Actually Happening in the Lyrics?

If you listen closely to Ahab the Arab, it’s basically a Three Stooges routine set in the Sahara. Ahab isn't a terrifying warlord; he's a goofy guy with a sweet tooth. The lyrics mention him eating "RC Cola and a Moon Pie," which is about as Southern as it gets. It’s this weird juxtaposition—a desert sheik enjoying snacks from a Tennessee general store—that gave the song its charm to 1960s American audiences.

The storytelling is frantic. Stevens describes Clyde the camel as having "low-slung, dual exhausts" and "chrome-plated fenders." He was tapping into the car culture of the early sixties, treating a camel like a hot rod. It’s absurd. It’s slapstick.

But then there's the elephant in the room: the "language."

✨ Don't miss: All Whitney Houston Songs: What Most People Get Wrong

Stevens spends a significant portion of the song speaking in what sounds like mock-Arabic. It’s mostly gibberish—rhythmic sounds designed to mimic a language he clearly didn't speak. In 1962, this was viewed as harmless "ethnic humor." By the time the 1980s and 90s rolled around, the perception started to shift. People began asking: Is this a tribute to a culture, or is it just making fun of one?

The 1970s Remix and the Shift in Perception

Most people don't realize that the version they hear on the radio today often isn't the 1962 original. Stevens actually re-recorded Ahab the Arab in 1969 for his album Gitarzan. This version is slicker, more produced, and leaned even harder into the comedy.

As the decades passed, the song became a litmus test for "cancel culture" before that term even existed. In the late 80s and early 90s, some radio stations quietly pulled it from their rotations. The American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC) eventually flagged Stevens’ work as being based on stereotypes.

Stevens, for his part, has always defended it as "good clean fun." He’s a comedian. To him, Ahab was a character just like the guy in "The Streak." He wasn't trying to make a political statement; he was trying to sell records to people who liked silly voices. Honestly, looking at his entire catalog, that checks out. He poked fun at everyone—hippies, rednecks, politicians, and himself.

👉 See also: Why the 80s Beauty and the Beast Series Still Haunts Our Dreams

Breaking Down the Musicality (It's Actually Pretty Complex)

Despite the goofy premise, the musical structure of Ahab the Arab is fascinating.

- The Hook: It uses a classic "Middle Eastern" scale (often the Phrygian dominant or the double harmonic scale) that instantly signals the setting to the listener.

- The Rhythm: It’s got a driving, rhythmic pulse that feels almost like a precursor to some of the more experimental pop of the late 60s.

- The Performance: Stevens' vocal range is legit. He jumps from a deep baritone to a piercing falsetto in seconds.

It’s easy to dismiss it as a joke song, but the arrangement required a lot of skill. You don't get to number five on the charts with just a funny voice; the song has to be "sticky." And Ahab was incredibly sticky.

The Legacy of the Camel Named Clyde

Is Ray Stevens a villain of music history? Probably not. Is the song problematic by 2026 standards? Absolutely. But that’s the thing about pop culture—it’s a time capsule.

Ahab the Arab represents a specific moment in American entertainment when the world felt very small and "other" cultures were often reduced to caricatures for the sake of a three-minute laugh. It’s a cousin to the old Warner Bros. cartoons or the "Orientalist" films of the 1940s.

Interestingly, Stevens continued to perform the song well into the 21st century at his theater in Branson, Missouri. His audience—mostly older fans who remember the 60s fondly—still eats it up. They see it as a nostalgic trip back to a time when comedy felt "simpler." Meanwhile, younger listeners discovering it on Spotify or YouTube often react with a mix of fascination and "wait, they allowed this?"

Why We Still Talk About It

The reason Ahab the Arab persists isn't just because of the controversy. It's because Ray Stevens is a master of the "earworm." He knows how to write a melody that lodges itself in your brain and refuses to leave. Whether you love it or hate it, once you hear "Ahab! The Sheik of the Burning Sands," you're going to be humming it for the next three hours.

It also serves as a crucial bridge in music history. It showed that comedy records could be massive commercial successes, paving the way for artists like Weird Al Yankovic later on. Stevens proved that a solo artist could build a "cinematic" world inside a song using nothing but their voice and some clever studio tricks.

What to Do Next if You're Exploring Ray Stevens

If you really want to understand the impact of Ahab the Arab and the career of Ray Stevens, don't just stop at the one song.

- Listen to the 1962 original vs. the 1969 remake. The production differences tell a huge story about how recording technology changed in just seven years.

- Contrast it with "Everything is Beautiful." It is genuinely wild that the same man who did the gibberish chanting in Ahab also wrote one of the most sincere, inclusive anthems of the 1970s. It shows the duality of the era.

- Check out his Nashville credits. Stevens wasn't just a "funny guy." He was a top-tier session musician and arranger who worked with legends.

Ultimately, Ahab the Arab is a reminder that music is never just about the notes. It’s about the context, the culture, and the way our perceptions of "funny" change as we grow up. You don't have to like the song to recognize that it changed the trajectory of novelty music forever.

✨ Don't miss: BTS Reaction to Kpop Demon Hunters: Why Jungkook Really Cried

If you're building a playlist of 1960s curiosities, this track is the definitive starting point. Just be prepared for the fact that, for better or worse, you’ll never get the image of a camel with dual exhausts out of your head. It’s part of the American songbook now, weirdness and all.