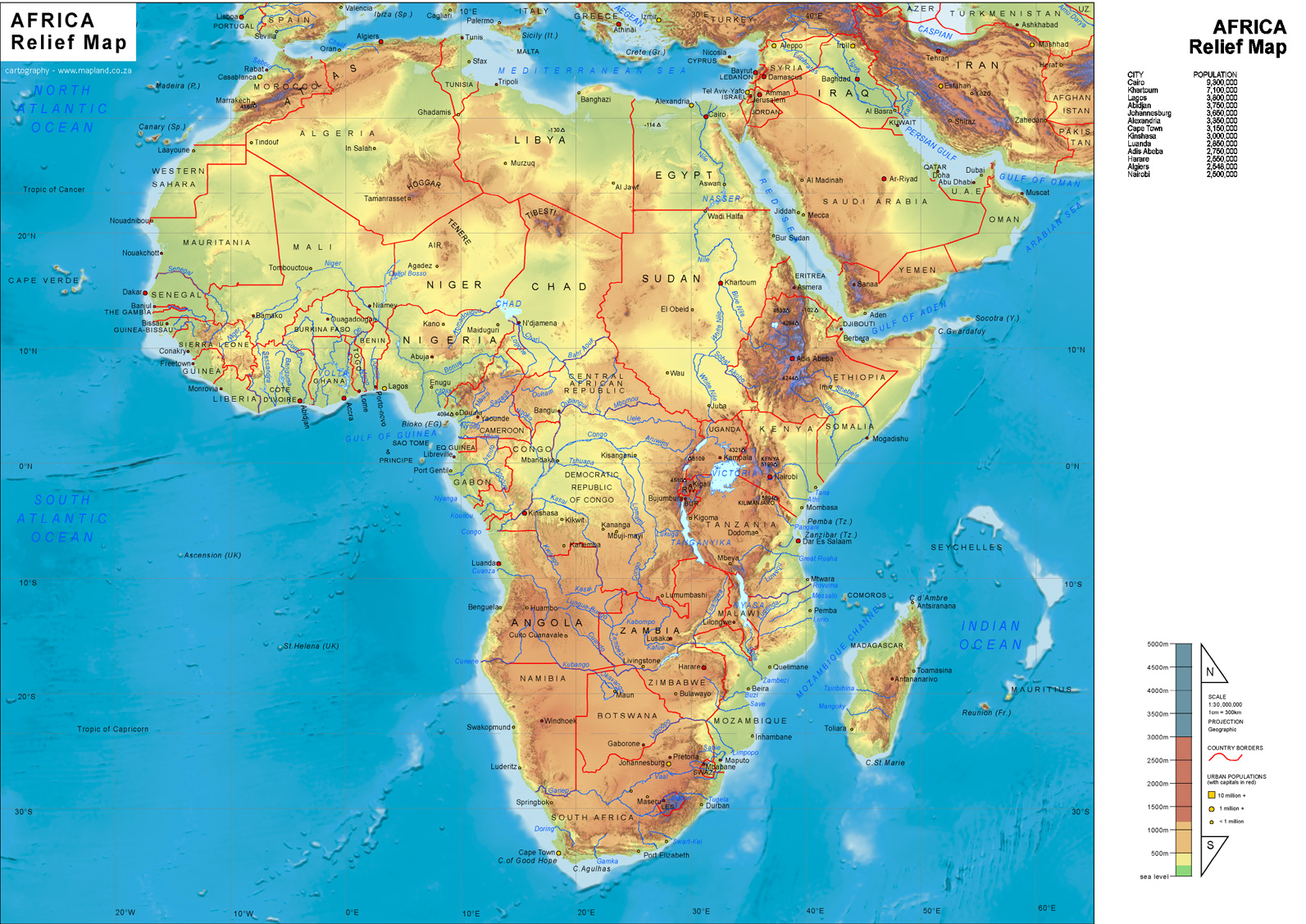

Africa is massive. Seriously, it's hard to wrap your head around just how much dirt and rock we’re talking about here. You’ve probably seen those viral graphics showing how the US, China, India, and most of Europe can all fit inside the African continent with room to spare. But looking at an Africa map physical map isn't just about realizing the sheer scale; it’s about understanding a landscape that is basically upside down compared to what most of us expect.

Most continents have a big mountain range running down one side, like the Andes or the Rockies, and then flat stuff everywhere else. Africa doesn’t play by those rules. It’s essentially a giant, raised plateau. If you could look at it from the side, it would look like a massive table sitting in the ocean.

💡 You might also like: Maldives Sea of Stars: What Most People Get Wrong About Seeing the Blue Glow

The Great Rift and why the continent is literally tearing apart

If you zoom into the eastern side of an Africa map physical map, you’ll see this jagged, deep scar running from the Red Sea all the way down to Mozambique. This is the East African Rift System. It’s not just a valley; it’s a tectonic divorce. The continent is pulling itself into two pieces.

Geologists like Dr. James Renwick have noted that this process is creating some of the deepest lakes on the planet. Take Lake Tanganyika. It’s the second deepest freshwater lake in the world, plummeting down over 4,700 feet. It’s so deep because the ground beneath it is literally opening up. This isn't like the Great Lakes in North America which were carved by ice; these are tectonic gashes.

When you look at the physical geography here, you notice a "Y" shape. One branch goes through Ethiopia, and the other curls around through Uganda and Tanzania. This movement is what gave us the "Mountains of the Moon" or the Rwenzori Mountains. They aren't volcanic. They are blocks of the earth’s crust that got shoved upward as everything else around them slumped down. It’s messy. It’s violent. It’s also why this part of the map is peppered with those long, skinny lakes that look like scratches on the earth’s surface.

The Sahara is not just a giant sandbox

People see the big tan blob on the top of an Africa map physical map and think "sand."

Honestly? Most of it is rock.

The Sahara is roughly the size of the United States, but only about 25% of it is actually dunes (what geographers call "ergs"). The rest is hamada—barren, rocky plateaus—and reg, which is just endless plains of gravel. If you were standing in the middle of the Tibesti Mountains in Chad, you wouldn't feel like you were in a desert movie; you’d feel like you were on Mars. These mountains are volcanic and reach heights of over 11,000 feet. Emi Koussi, the highest point in the Sahara, is an extinct shield volcano that’s so big it has its own microclimate.

What’s wild is that the Sahara hasn't always been this way. About 6,000 to 10,000 years ago, it was the "Green Sahara." We have satellite imagery and physical soil samples that show ancient riverbeds, called paleochannels, buried under the sand. The physical map we see today is just a snapshot in a cycle that flips every 20,000 years or so due to a wobble in Earth's axis.

The Congo Basin and the "Green Heart"

Right in the center of the continent sits the Congo Basin. It’s the world’s second-largest tropical rainforest. On a physical map, this shows up as a deep, dark green depression.

💡 You might also like: Eurostar travel from london to paris: What Most People Get Wrong

The Congo River is the real star here. It’s the deepest river in the world, with sections reaching over 700 feet deep. Because the river flows through a massive, flat basin before hitting a series of intense rapids near the coast (the Livingstone Falls), it creates a unique biological trap. Fish on one side of the river have evolved into different species than fish on the other side because the current is too strong for them to cross.

Unlike the Amazon, which is relatively flat, the Congo Basin is surrounded by high ground. It’s a literal bowl. This geography traps moisture and creates a self-sustaining weather system. It’s one of the most carbon-dense places on Earth, specifically the Cuvette Centrale peatlands, which store about 30 billion tons of carbon. If that physical feature ever dries out, we’re all in trouble.

Why Africa has no "Great Mountain Chain"

If you look at a physical map of South America, the Andes are obvious. If you look at Asia, the Himalayas jump out. Africa is different. It has "islands" of high elevation.

You have the Atlas Mountains in the far northwest, which are actually part of the same geological event that created the Alps in Europe. Then you have the Ethiopian Highlands—often called the "Roof of Africa." This is a massive block of basaltic lava that was pushed up millions of years ago. It’s why Ethiopia was never fully colonized; the physical geography is a nightmare for an invading army. It’s rugged, steep, and sits at an average of 15,000 feet.

Then, of course, there’s Kilimanjaro.

👉 See also: Chennai Tamil Nadu: Why Most People Get It Totally Wrong

It’s the highest point on the continent, but it’s not part of a range. It’s a "free-standing" mountain. It’s basically a giant volcano sitting alone on the plains of Tanzania. This is a recurring theme on the African physical map: isolated massifs and high plateaus rather than long, continuous folded mountain chains.

The Southern Cape and the Great Escarpment

Down south, the geography gets weird again. There is a feature called the Great Escarpment. It’s a massive cliff face that rims the southern part of the continent.

If you’re in Cape Town or Durban and you want to go inland, you have to go up. In some places, like the Drakensberg in South Africa and Lesotho, these cliffs rise to over 11,000 feet. This escarpment has dictated where people live and how trade happened for centuries. It’s a massive wall of basalt that separates the narrow coastal plains from the high internal plateau (the Highveld).

Because of this "table-top" structure, African rivers are generally terrible for navigation. In Europe or North America, you can take a boat deep into the interior. In Africa, you hit a massive waterfall or a series of rapids pretty quickly because the water is falling off the edge of the plateau. This is why the interior of Africa remained a mystery to outsiders for so long—the physical map literally barred the way.

Understanding the "High" and "Low" Africa

Geographers often split the continent into "High Africa" and "Low Africa."

If you draw a line from roughly the middle of Angola up to the Red Sea, everything to the southeast is High Africa. This area is mostly above 3,000 feet. Everything to the northwest is Low Africa, where the elevations are much lower, except for the occasional volcanic peak or the Atlas Mountains.

This split explains almost everything about the continent's climate and economy. High Africa is cooler and generally has more mineral wealth (think gold and diamonds in South Africa or copper in Zambia). Low Africa is dominated by the massive sedimentary basins like the Sahara and the Niger River delta.

Actionable insights for using an Africa physical map

If you are studying an Africa map physical map for travel, business, or education, stop looking at it as a static piece of paper. It’s a living system.

- Check the Elevation Shading: Don't just look at the colors. Green doesn't always mean "forest." In some maps, it just means "low elevation." Look at the contour lines in the Afar Triangle (the depression where the Rift begins) to see land that is actually below sea level.

- Trace the Water: Follow the Nile. It’s the only major river in the world that flows from the humid tropics, through a bone-dry desert, and into the sea without drying up. Seeing the "S" shape of the Nile on a physical map explains why ancient Egyptian civilization stayed in such a narrow strip.

- Look for the Endorheic Basins: These are places where water flows in but never flows out to the ocean. Lake Chad is the most famous. Its size on a physical map is a lie—it shrinks and grows so much that a map from 1960 looks nothing like a map from 2026.

- Analyze the "Hinges": Look at the Cameroon Line, a string of volcanoes that starts in the Atlantic Ocean (as islands like Bioko) and continues onto the mainland as Mount Cameroon. It’s a literal "leak" in the earth's crust.

The physical reality of Africa is one of extremes. It's a continent of high plateaus, deep gashes, and isolated peaks that have shaped the history of every person living there. When you look at the map, you aren't just seeing geography; you're seeing the physical obstacles and opportunities that have defined human evolution and global trade for millennia.

To truly understand Africa, you have to stop thinking of it as a flat surface and start seeing it as a massive, tilted table, scarred by the forces of the earth's interior. Focus on the Great Escarpment and the Rift Valley; those two features alone explain more about the continent's soul than any political border ever could.