Look, let's be real for a second. Staring at a graph of Marginal Revenue and Marginal Cost until your eyes cross isn't anyone's idea of a Friday night. I've been there. You're trying to figure out if the firm is making a profit, breaking even, or if they should just pack it up and shut down. It's confusing. But having a solid AP Microeconomics cheat sheet isn't just about memorizing some lines; it’s about understanding the "why" behind the "what."

Most students treat the AP Micro exam like a giant vocabulary test. Big mistake. Huge. The College Board loves to trip you up on the relationships between variables, not just the definitions. If you don't know that $MR = MC$ is the golden rule for profit maximization, you're basically toast.

The Absolute Essentials of Your AP Microeconomics Cheat Sheet

The heart of micro is the firm. If you can’t draw a perfectly competitive firm in long-run equilibrium in under thirty seconds, you need to practice. It’s the bread and butter of the exam. You have your Price, which is equal to Marginal Revenue because the firm is a price taker. Then you’ve got that U-shaped Average Total Cost (ATC) curve.

Where do they touch?

They touch at the minimum of the ATC. This is what we call productive efficiency. If you’re looking at your AP Microeconomics cheat sheet and it doesn't emphasize the difference between productive efficiency ($P = \text{min } ATC$) and allocative efficiency ($P = MC$), you should probably toss it.

Elasticity is Kinda Everything

People overcomplicate elasticity. Honestly, it’s just a measure of how much people care about price changes. If the price of insulin goes up, people still buy it. That’s inelastic. If the price of a specific brand of blue corn chips goes up, people buy the yellow ones instead. That’s elastic.

You need to remember the Total Revenue Test. It's a lifesaver. If price and total revenue move in the same direction, you’re in the inelastic range. If they move in opposite directions, you’re elastic. Think of it like a see-saw.

Market Structures: The Four Horsemen

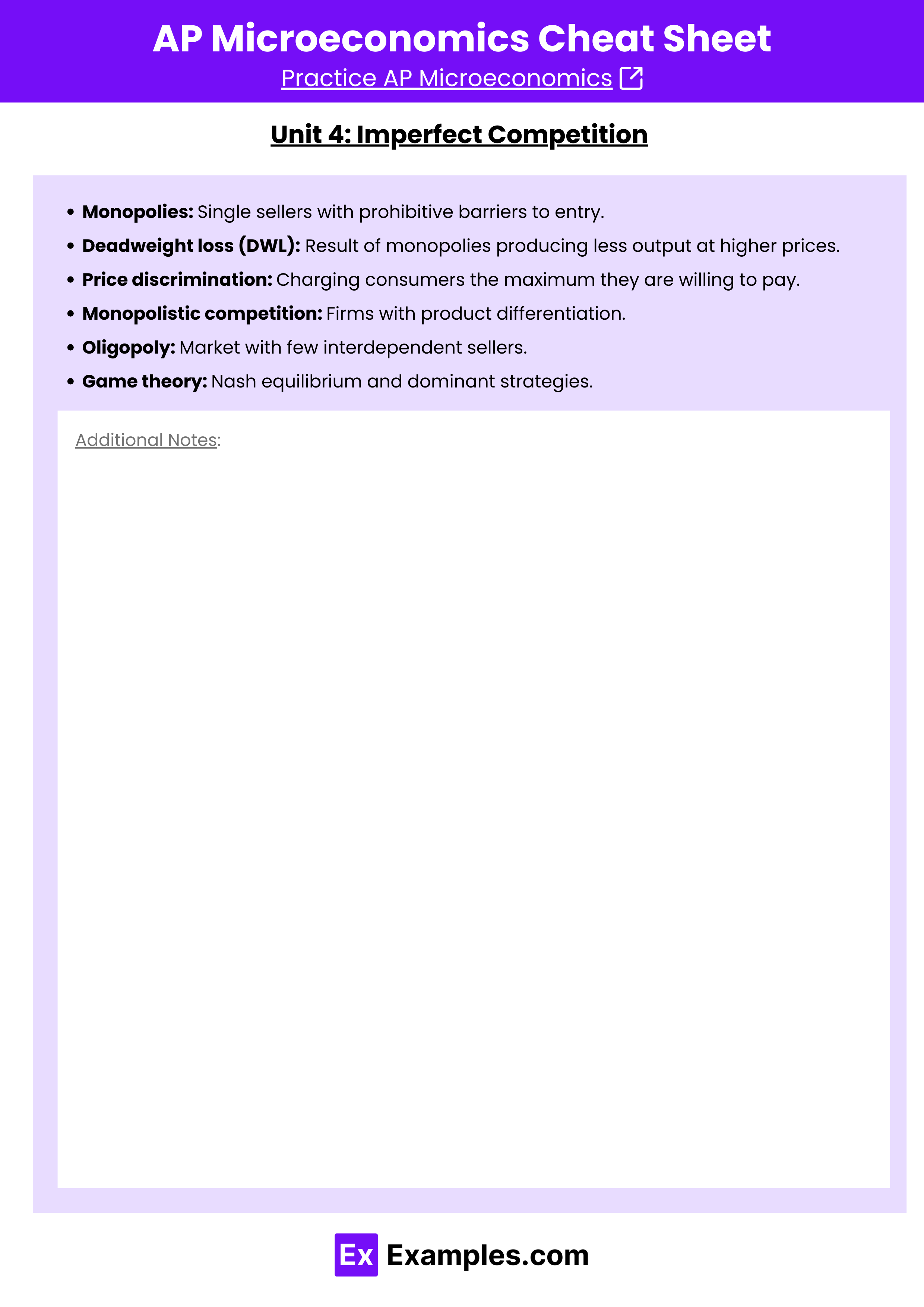

You've got Perfect Competition, Monopolistic Competition, Oligopoly, and Monopoly. It sounds like a lot, but they’re just points on a spectrum of power.

Perfect competition is the "dream" where everyone is small and nobody has power. On the flip side, a Monopoly is the "villain" with all the power, charging higher prices and producing less than what’s socially optimal. This creates Deadweight Loss (DWL). If you see a triangle pointing toward the socially optimal quantity on a graph, that’s almost certainly your DWL.

Monopolistic competition is where things get weird. It’s like fast food. Every burger is a little different (product differentiation), so they have some control over price, but in the long run, they still make zero economic profit because new taco shops keep opening up next door.

Oligopolies are the ones with the Game Theory tables. You know the ones—the Nash Equilibrium boxes where you have to figure out if Boeing and Airbus are going to collude or cheat. Hint: they usually want to collude, but the incentive to cheat is just too strong.

The Factor Market: Where Students Usually Tank

Most people spend so much time on the product market that they forget about the factor market. This is where firms buy resources like labor. Instead of $MR = MC$, we use $MRP = MRC$.

$MRP$ is just the Marginal Revenue Product—basically, how much extra cash a worker brings in. $MRC$ is the Marginal Resource Cost, or how much it costs to hire them.

You hire until they equal each other. If the worker brings in $20 and costs $15, hire them. If they bring in $20 and cost $21, let them go. It’s logic, but in the heat of a timed exam, it feels like rocket science.

Why Externalities Ruin Everything

The "invisible hand" of Adam Smith is great until someone starts dumping chemicals in a river. That’s a negative externality. When the market fails to account for these costs, we overproduce. The government has to step in with a tax—often called a Pigouvian tax—to shift the supply curve back to where it should be.

Positive externalities are the opposite. Think vaccines or education. The market doesn't produce enough because people don't realize the full benefit. So, the government hands out subsidies.

How to Actually Use Your AP Microeconomics Cheat Sheet During Prep

Don't just read it. That's passive learning and it's mostly a waste of time. Instead, use your AP Microeconomics cheat sheet to "reverse engineer" Free Response Questions (FRQs).

Take a prompt from 2023 or 2024. Look at the graph they want you to draw. Then, find that specific section on your sheet. If you can’t explain why the ATC curve is below the price line for a firm making a profit, you don't actually know the material yet.

- Draw the graph from memory.

- Check your cheat sheet for the labels ($P$, $Q$, $D$, $MR$, $MC$, $ATC$).

- Shade the profit or loss area.

- Identify the socially optimal point.

If you miss a label, mark it in red. The College Board graders are notoriously picky about labels. If you write "M" instead of "MC," you might lose the point. It’s brutal, but that’s the game.

💡 You might also like: Converting 50 Rupees to Dollars: Why This Small Amount Tells a Huge Story

Common Traps That Kill Your Score

A big one is confusing a change in "Quantity Demanded" with a "Change in Demand." One is a slide along the curve (usually caused by price), and the other is a literal shift of the entire curve (caused by tastes, income, or other shifters).

Another trap? Thinking that "Accounting Profit" and "Economic Profit" are the same. They aren't. Economic profit subtracts implicit costs—like the salary you gave up to start your own business. If a firm has zero economic profit, they're actually doing okay. They're making enough to cover all their costs and their next best alternative. We call this a "normal profit."

Final Tactical Steps for Success

To turn a basic AP Microeconomics cheat sheet into a 5 on the exam, you need to transition from recognition to recall.

Start by categorizing every graph into three buckets: Market, Firm, and Factor.

Next, master the "side-by-side" graph. This is where you show the industry on the left and the individual firm on the right. If the industry demand increases, the price goes up for the firm. You have to be able to draw that dotted line connecting the two.

Focus on the "Shut Down Rule." If the Price drops below the Average Variable Cost ($AVC$), the firm should stop production immediately. If they stay open, they're losing more money than if they just paid their fixed costs (like rent) and went home.

Finally, do not sleep on the concept of Diminishing Marginal Returns. It’s why the $MC$ curve eventually goes up. As you add more workers to a kitchen with only one stove, they start getting in each other's way. Productivity drops. Costs go up.

Stop highlighting your textbook and start drawing. Grab a blank stack of paper, your cheat sheet, and a timer. If you can't recreate the Monopoly graph with consumer surplus and deadweight loss labeled in under two minutes, keep practicing until you can. Consistency beats cramming every single time.

Check the official College Board site for the latest "Course and Exam Description" (CED) to ensure your sheet matches the current unit weights, as they occasionally tweak the percentage of questions dedicated to specific topics like market failure or labor markets. Get your labels right, watch your shifters, and don't forget that economic profit is always smaller than accounting profit.