Béla Bartók was dying when he wrote it. That’s the heavy truth hanging over the Bartók Concerto for Orchestra, a piece that basically redefined what a modern symphony could sound like while the world was literally on fire. It was 1943. Bartók was in a New York hospital, skin and bones, struggling with what we now know was leukemia. He was a refugee, broke, and convinced his career was over. Then Serge Koussevitzky, the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, walked into his room with a $1,000 commission.

It changed everything.

Most people hear "concerto" and think of a lonely violinist standing in front of a giant group of musicians. This is different. Bartók treats every single person on that stage like a virtuoso. One minute the brass is screaming; the next, two bassoons are having a weird, playful conversation. It’s a flex. He wanted to show that an entire orchestra could be the soloist.

Honestly, the piece is a miracle. It’s dark, it’s funny, it’s angry, and it ends with a massive, life-affirming shout. If you’ve ever felt like the world was against you, this music is basically your soundtrack.

The Weird Genius of the Structure

Bartók didn’t just throw notes at a page. He was obsessed with symmetry. He loved the "arch form," which is a fancy way of saying the piece is shaped like a bridge. The first and fifth movements are big and fast. The second and fourth are lighter and more rhythmic. Right in the middle—the third movement—is the "Elegy." It’s the heart of the work, and it’s haunting.

Some people call this "night music." Bartók had this habit of mimicking the sounds of the Hungarian countryside at 3:00 AM. You hear these shimmering strings, tiny chirps from the woodwinds, and sudden, eerie whispers. It doesn’t sound like a postcard. It sounds like being lost in a forest where the trees are watching you.

Why call it a "Concerto" and not a "Symphony"?

The title matters. By calling it the Bartók Concerto for Orchestra, he was making a point about democracy in music. In a standard symphony, the first violins usually do all the heavy lifting while the tuba player sits there counting rests for twenty minutes. Not here. Bartók forces the second violins to lead. He makes the harps play things that seem impossible. He gives the percussionists a workout.

It’s about the "soloistic" treatment of sections. You’ll hear a pair of oboes play a melody, then the trumpets take it over, then the cellos. It’s a constant hand-off. It’s a conversation where everyone is equally smart and slightly caffeinated.

That Shostakovich "Diss Track" in the Fourth Movement

Let’s talk about the drama. The fourth movement, the Intermezzo interrotto (interrupted intermezzo), is famous for being one of the greatest "trolls" in classical music history.

Bartók was listening to the radio in his hospital bed and heard Dmitri Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, the "Leningrad." At the time, that symphony was a massive propaganda hit. But Bartók? He hated it. He thought the main theme was repetitive and, frankly, annoying.

So, in the middle of his own beautiful, folk-inspired movement, Bartók suddenly introduces this goofy, circus-like tune. It’s a direct parody of Shostakovich. He then has the trombones "raspberry" the theme with loud, sliding glissandos. It’s the musical equivalent of a middle finger. Most listeners miss the joke because it’s tucked inside such sophisticated music, but once you hear it, you can’t unhear it.

It shows his personality. Even when he was facing death, he had enough fire left to make fun of a rival.

Folk Music but Make it Modern

Bartók wasn’t just a composer; he was an ethnomusicologist. He literally traveled through rural Hungary, Romania, and North Africa with a primitive phonograph, recording peasants singing. He didn’t want to just copy-paste these tunes into his music. He wanted to absorb the DNA of the scales.

In the Bartók Concerto for Orchestra, you don’t get "Mary Had a Little Lamb." You get odd rhythms. You get the "Golden Section" and Fibonacci sequences hidden in the phrase lengths.

- Rhythmic Vitality: The fifth movement is a masterclass in energy. It uses a "perpetual motion" technique that feels like a high-speed chase.

- The Scale Work: He often used the acoustic scale or octatonic scales, which give the music a flavor that isn't quite major and isn't quite minor. It’s spicy.

- The Brass Chorales: There are moments, especially in the second movement ("Game of Pairs"), where the brass section sounds like a grand cathedral organ. It’s breathtaking.

The Boston Premiere and the "Happy Ending"

The piece premiered on December 1, 1944. Bartók was there. He shouldn't have been—he was too sick—but he made it. The audience went wild. It was an instant success, which is rare for "modern" music.

Interestingly, there are actually two endings. Bartók originally wrote a shorter, more abrupt ending. But Koussevitzky convinced him that the piece deserved something more grand. Bartók went back and wrote the longer, "big" ending we usually hear today, with the trumpets screaming to the rafters. It feels like a triumph over the illness that was killing him. He lived long enough to see the success, dying just less than a year later in September 1945.

How to Actually Listen to It

If you’re new to this, don’t try to analyze it. Just feel the textures.

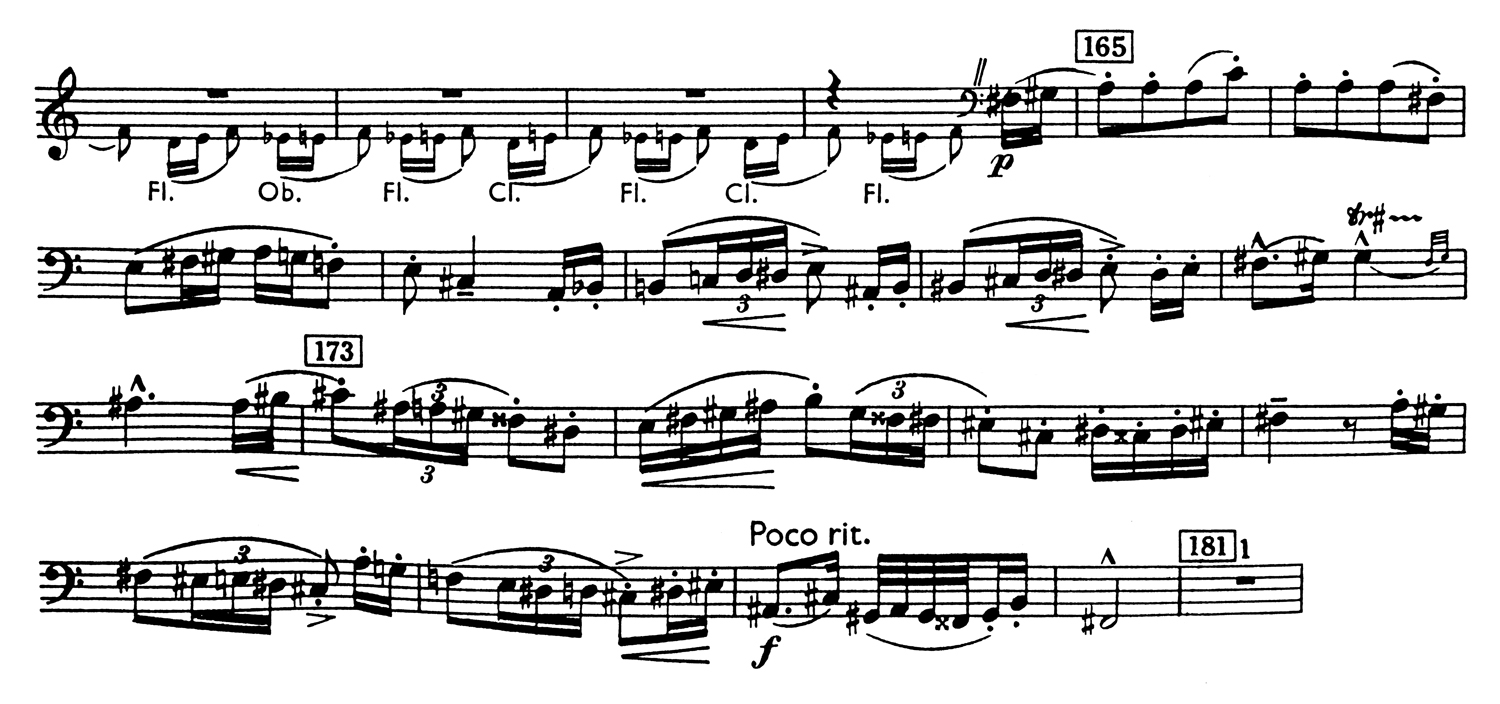

Start with the second movement, "Giuoco delle coppie." It’s literally a "game of pairs." Two bassoons play together, then two oboes, then two clarinets, then two flutes, then two muted trumpets. Each pair is separated by a specific musical interval (sixths, fifths, fourths, thirds, and seconds). It’s like a mathematical dance.

Then, skip to the finale. It’s pure adrenaline. The way the strings scurry around is enough to give any professional violinist a panic attack.

✨ Don't miss: Sophie Hatter from Howl's Moving Castle: Why Her Magic is So Often Misunderstood

Actionable Insights for the Modern Listener

To truly appreciate the Bartók Concerto for Orchestra, you need to go beyond just hitting play on Spotify.

Compare the Great Conductors

Not every performance is the same. Fritz Reiner with the Chicago Symphony (1955) is often considered the "gold standard" because Reiner knew Bartók personally. It’s sharp, precise, and terrifyingly fast. For something more lush and modern, check out Pierre Boulez with the Chicago Symphony or Georg Solti. Solti brings a Hungarian grit to it that feels authentic.

Watch a Live Performance (or Video)

This is a visual piece. Seeing the "Game of Pairs" where the woodwind players stand up or lean in to communicate with their partners makes the "concerto" aspect click. You realize it’s a team sport.

Listen for the Trombones in the Fourth Movement

Specifically at the 3:10 mark (depending on the recording). That’s the "raspberry." Once you hear the disrespect Bartók had for that Shostakovich theme, the whole movement becomes a comedy rather than just a pretty folk song.

Read the Score (if you can)

Even if you don't read music well, looking at a "study score" of this piece reveals the symmetry. You can literally see the patterns on the page. It looks like architecture.

Contextualize the "Night Music"

Listen to the third movement in the dark. No phone. No distractions. Bartók was trying to capture the feeling of the night in a world at war. It’s supposed to feel uncomfortable. It’s supposed to feel like the earth is breathing.

The Bartók Concerto for Orchestra isn't just a museum piece. It’s a survival manual set to music. It proves that even when you’re at your lowest point—physically, financially, and emotionally—you can still create something that sounds like a victory.