You’ve probably seen them in high school textbooks. Those pinkish-red circles that look like tiny donuts. They’re everywhere in science memes and medical stock photos, but seeing blood under microscope labeled correctly is a whole different ballgame when you’re actually in a lab. It’s messy. It’s chaotic. Honestly, without those labels, a blood smear looks like a Jackson Pollock painting made of cells.

Most people think blood is just red liquid. It’s not. It’s a complex tissue. When you smear a drop on a glass slide and hit it with Wright’s stain, a hidden universe pops out. But here’s the thing: if you don't know what you're looking at, you're just looking at purple blobs.

🔗 Read more: Eye Drops Para Qué Sirve: Choosing the Right Solution for Your Vision

What You’re Actually Seeing in a Labeled Blood Smear

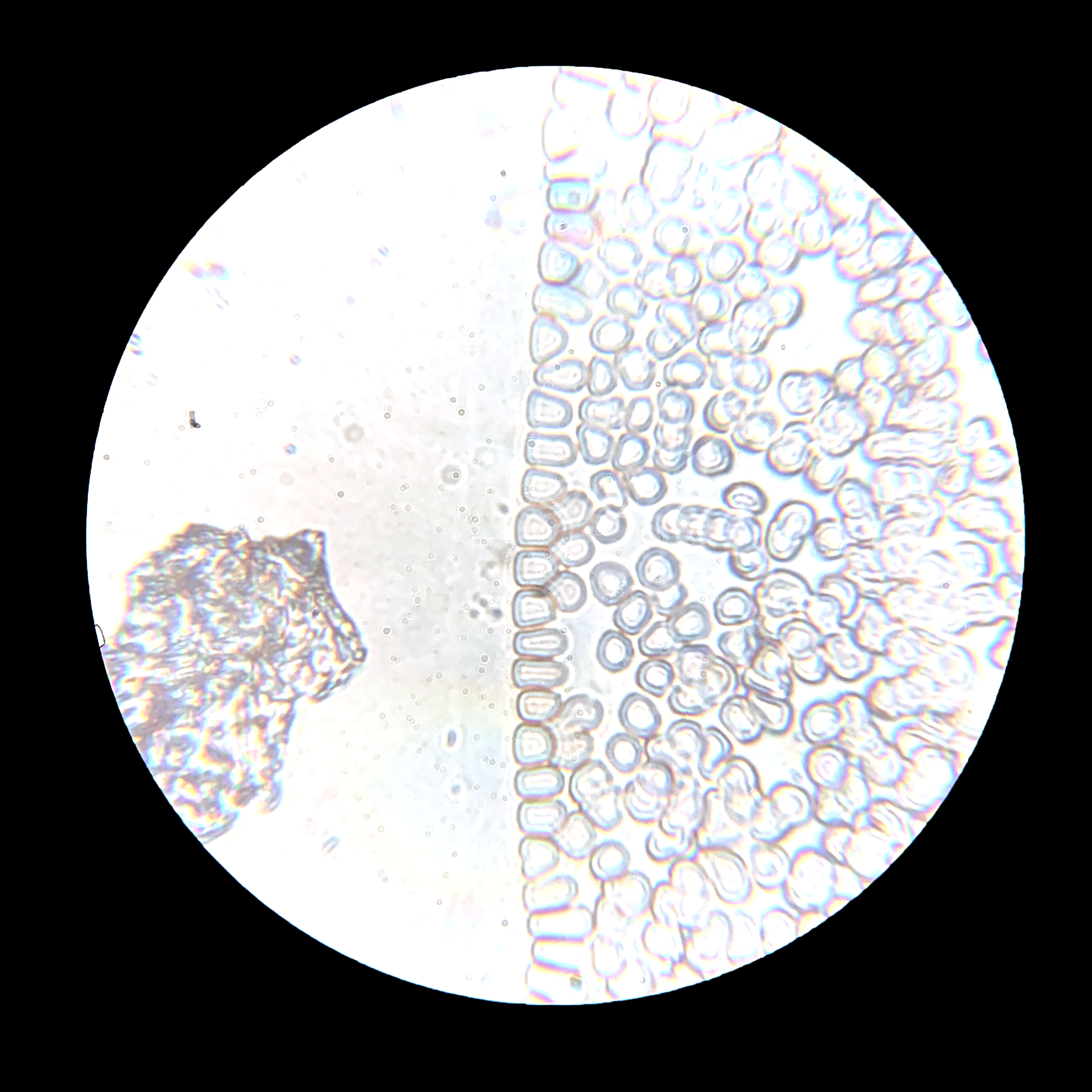

The first thing that hits you is the sheer number of Red Blood Cells (RBCs). Scientists call them erythrocytes. They don't have a nucleus. That’s why they have that pale center—it’s a biconcave shape that allows them to squeeze through tiny capillaries. If you see a blood under microscope labeled diagram, the RBCs are the background actors. They’re the "filler" that carries oxygen.

Then come the White Blood Cells (WBCs). These are the rockstars.

Leukocytes are way rarer than red cells. In a healthy person, you might see one white cell for every six hundred or seven hundred red ones. If you see way more than that, someone is probably fighting an infection or, in worse cases, dealing with leukemia. Professionals like hematologists look for very specific markers to tell them apart. It’s not just "a white cell." It’s a Neutrophil with its multi-lobed nucleus that looks like a bunch of sausages tied together. Or it's a Lymphocyte, which is basically a giant purple nucleus with a tiny rim of blue cytoplasm.

The Breakdown of the "Big Five"

- Neutrophils: These are the first responders. They eat bacteria. Under a microscope, they have 3 to 5 lobes in their nucleus. If you see "band cells" (immature neutrophils), it means the body is screaming for help and pumping out babies to fight an infection.

- Lymphocytes: Tiny but mighty. They handle viruses and make antibodies. They look like a solid dark circle.

- Monocytes: The garbage collectors. They’re huge. Often they have a kidney-bean-shaped nucleus.

- Eosinophils: These look like they’re wearing bright orange sunglasses under the right stain. They deal with parasites and allergies.

- Basophils: The rarest ones. They’re so full of dark granules you can barely see the nucleus. They’re the ones responsible for the histamine response that makes your life miserable during hay fever season.

Why Labeling Changes Everything for Diagnosis

Let's get real. A computer can "see" cells, but a trained human eye looking at blood under microscope labeled samples is still the gold standard in many pathology labs. Take Sickle Cell Anemia. In a standard smear, the cells aren't round; they're curved like a crescent moon. If a lab tech doesn't label that correctly, the treatment plan stalls.

Or consider malaria.

Malaria is terrifyingly beautiful under a 100x oil immersion lens. You’ll see tiny "rings" inside the red blood cells. Those are Plasmodium parasites. Without a label pointing out that "ring form," a student might just think it’s a smudge on the lens. Real expertise is knowing the difference between a piece of dust and a parasite that can end a life.

It's about the morphology. That’s just a fancy word for "shape." If the red cells are too small (microcytic), you might be looking at iron deficiency. If they’re too big (macrocytic), maybe it’s a Vitamin B12 issue. The labels are the bridge between a "cool picture" and a medical diagnosis.

The Art of the Peripheral Blood Smear

You can’t just dump a bucket of blood on a slide. You need a "feathered edge." This is a specific area on the slide where the cells are spread out in a single layer. If they’re piled on top of each other, you can’t see anything. It’s just a red wall.

Technicians use a second slide to drag the blood across the first one. It takes practice. Too fast and the cells burst. Too slow and they clump. Once it’s dried and stained, that’s when the blood under microscope labeled process begins.

I once talked to a lab tech who had been doing this for thirty years. She told me she could "smell" a bad slide before she even looked at it. That’s probably an exaggeration, but the intuition involved is insane. She could spot a "smudge cell"—a fragile white blood cell that burst during the smearing process—and know instantly it was a sign of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL).

Common Misconceptions About What You See

People think platelets are cells. They aren't. They’re just fragments of a much larger cell called a megakaryocyte. Under the microscope, they look like tiny purple specks of dust scattered between the red cells. If they're clumped together, it might mean the blood was drawn poorly, or it could mean a clotting disorder.

Another big mistake? Thinking every "blue spot" is a white cell. Sometimes it’s just "precipitated stain." Basically, the dye didn't wash off properly. This is why looking at blood under microscope labeled by an actual expert is better than trusting a random Google Image search. Professionals know how to ignore the "trash" on the slide.

Nuance in Staining Techniques

Not all stains are equal. Most labs use:

- Wright’s Stain: The classic. Best for looking at cell types.

- Giemsa Stain: Great for finding parasites like malaria or Babesia.

- Leishman Stain: Similar to Wright's, often used in different regions of the world.

Each of these changes how the "labels" look. A neutrophil might look slightly more purple or more pink depending on the pH of the buffer used. It’s a chemistry experiment on a 1x3 inch piece of glass.

Practical Steps for Identifying Cells Yourself

If you’re a student or just a curious person with a home microscope, don't expect it to look like the textbook immediately. You need a high-power objective lens (usually 40x or 100x with oil) to see the details of the nucleus.

💡 You might also like: Healthy Pumpkin Smoothie Recipe: Why Your Blender Version Is Probably Just Liquid Pie

- Start with the Red Cells: Ensure they are mostly uniform. If you see "target cells" (cells that look like a literal bullseye), that's a huge red flag for things like Thalassemia.

- Hunt for the Purple: Scan the slide until you find something purple. That's a white cell.

- Check the Nucleus: Is it one solid piece? Is it lobed? This is your biggest clue.

- Look at the Cytoplasm: Are there grains (granules) in there? If it's grainy, it's likely a neutrophil, eosinophil, or basophil. If it's smooth, it's a lymphocyte or monocyte.

Understanding blood under microscope labeled samples isn't just for passing a biology quiz. It’s the foundation of modern hematology. It’s how we catch infections, monitor cancers, and understand the basic building blocks of our survival.

Next time you see one of those labeled images, look past the red circles. Look for the weird stuff. The "Auer rods" in leukemia, the "Howell-Jolly bodies" in people without a spleen, or the "schistocytes" which are basically red blood cells that have been ripped apart by mechanical stress. The blood tells a story, and the labels are just the subtitles.

To get better at this, start by comparing "Normal" smears with "Pathological" ones side-by-side. Use resources from the American Society of Hematology (ASH) or the CDC’s DPDx for parasite identification. These sites provide high-resolution, peer-reviewed labeled images that are far more reliable than generic search results. Practice identifying the "Big Five" white cells until you can spot a Monocyte from a mile away. It’s a skill that takes time, but once you see the patterns, you’ll never look at a drop of blood the same way again.