March 1965. A skinny kid from Minnesota walks into Columbia Recording Studios in New York City. He’s got an acoustic guitar, a harmonica rack, and—crucially—a Fender Stratocaster. What happened over the next three days didn’t just change folk music. It basically broke the existing rules of what a "pop" star was allowed to be. People still argue about it today. When you listen to Bob Dylan Bringing It All Back Home, you aren't just hearing an album; you’re hearing the exact moment the sixties stopped being polite and started getting weird.

It was half electric. Half acoustic. Total chaos.

The Day the Acoustic Purists Lost Their Minds

Before this record, Dylan was the "voice of a generation." He was the protest guy. The "Blowin' in the Wind" guy. If you were a folk fan in 1964, you expected him to wear work shirts and sing about social justice over three chords. Then comes the opening track of the new album: "Subterranean Homesick Blues."

It’s loud. It’s snotty. It’s got a beat you can actually dance to.

Dylan’s delivery on that track is basically proto-rap. He’s spitting out internal rhymes about pump valves and medicine at a breakneck pace. "Johnny’s in the basement / Mixing up the medicine / I’m on the pavement / Thinking about the government." It’s frantic. Honestly, it sounded like a middle finger to the coffeehouse crowd who wanted him to stay in a box. Producer Tom Wilson, who had previously worked with Simon & Garfunkel, was the secret weapon here. He helped Dylan bridge that gap between the Greenwich Village folk scene and the raw energy of rock and roll.

The backlash was immediate. And loud.

When Dylan took this sound to the Newport Folk Festival later that year, people booed. They called him "Judas" later on in Manchester. But Bob Dylan Bringing It All Back Home was the blueprint. It proved that you could have high-art lyrics—the kind of stuff people studied in poetry class—and still have a band that kicked like a mule.

Side One: The Electric Freak-Out

The first half of the record is a fever dream. You've got tracks like "Maggie’s Farm," which is essentially a public resignation letter. "I ain't gonna work on Maggie's farm no more." He wasn't just talking about a farm. He was talking about the folk movement. He was done being a mascot.

The musicianship on the electric side is loose. Some critics at the time hated it. They thought it sounded sloppy. But that’s the point. It has this garage-band energy that felt dangerous. On "Outlaw Blues," Dylan is leaning into a persona that’s half-rockabilly, half-rimbaud. He sounds like he’s having the time of his life, which was a huge shift from the solemn, "finger-pointing" songs of his previous records like The Times They Are A-Changin'.

Then there’s "Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream." It starts with a false start where Dylan just bursts out laughing. They kept that in the final cut. Why? Because it showed the artifice was gone. It wasn't a polished product; it was a document of a guy in a room making noise with his friends. The song itself is a surrealist retelling of the discovery of America, involving encounters with Captain Arab (a play on Ahab) and the police. It’s hilarious and deeply cynical all at once.

🔗 Read more: Spin Doctors Lyrics Two Princes: Why That 90s Rhyme Scheme Still Works

The Lyrics Aren't Just Words—They're Rorschach Tests

Dylan was reading a lot of beat poetry at the time. Jack Kerouac. Allen Ginsberg. You can hear that influence dripping off every line. He stopped writing about specific events—like the death of Hattie Carroll—and started writing about feelings and hallucinations.

Take "Love Minus Zero/No Limit." It’s a love song, sure. But it’s full of lines like "In the quarters of the night / Fish-and-ladder shadows eat the ice." What does that mean? It doesn't matter. It feels like something. That was the breakthrough of Bob Dylan Bringing It All Back Home. He gave listeners permission to not understand everything literally.

Side Two: The Acoustic Hallucination

If Side One was the party, Side Two is the 3:00 AM comedown. It’s entirely acoustic, but it’s not the folk music of 1962. This is "folk-baroque."

"Mr. Tambourine Man" is the centerpiece. Interestingly, Dylan had actually recorded a version of this during the Another Side of Bob Dylan sessions, but it didn't make the cut. The version we get here is perfect. It’s a prayer for inspiration. It’s a plea to be taken away from the mundane world. When The Byrds covered it and took it to number one, they changed the arrangement, but they couldn't touch the sheer poetic depth of Dylan’s original four-verse odyssey.

Then the album closes with three of the most intense songs ever put to tape:

- It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding): A scathing, cynical takedown of consumerism and hypocrisy. "He not busy being born is busy dying." People still quote that in commencement speeches. It’s a relentless, breathless performance.

- Gates of Eden: Pure surrealism. It’s dense and difficult to unpack.

- It's All Over Now, Baby Blue: The final goodbye. It sounds like a breakup song, but most Dylanologists agree it’s a breakup song to his own past. He’s leaving the old world behind. "Strike another match, go start anew."

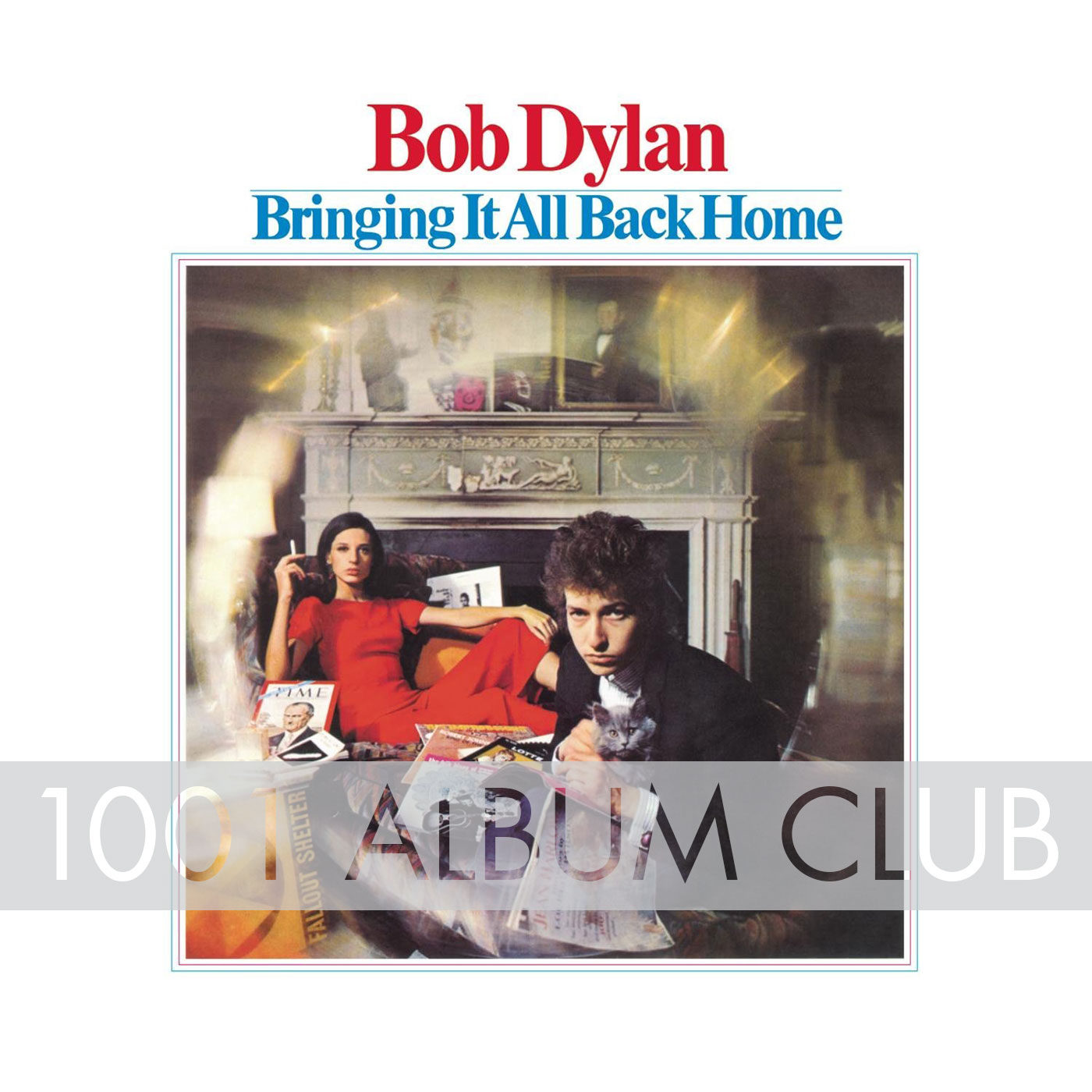

Why the Cover Art Mattered

Look at the album cover. It’s a wide-angle shot taken at manager Albert Grossman’s house. Dylan is sitting there, looking cool and bored, holding a cat. Behind him is Sally Grossman in a red dress. There are artifacts scattered around—magazines, a Fallout Shelter sign, other albums.

🔗 Read more: How to actually find Over the Garden Wall watch online free options without the headaches

This was the first time Dylan looked like a rock star. He wasn't the hobo-chic kid anymore. He was the center of the cool universe. The blur around the edges of the photo suggests a world in motion, which is exactly what the music was doing. It was a visual cue that the "Old Weird America" was merging with the "New Mod London/New York" scene.

The Lasting Impact on Music History

Without Bob Dylan Bringing It All Back Home, the Beatles might have stayed writing "I Want to Hold Your Hand" style pop for a lot longer. Lennon was famously obsessed with this era of Dylan. It gave the rest of the industry permission to grow up. It proved that you could be popular and intelligent. You could be loud and literate.

It also birthed "Folk Rock" as a genre. Suddenly, everyone was plugging in. The acoustic purists felt betrayed, but the rest of the world felt electrified. The album peaked at #6 on the Billboard 200, which was huge for something this experimental.

What Most People Miss

People often focus on the "going electric" part as a rebellion against the fans. But if you look at Dylan’s history, he was always a rock and roller. He played in rock bands in high school. He loved Little Richard. Bringing the electric guitar back wasn't a betrayal; it was a homecoming. That’s likely where the title comes from. He was bringing his music back to the rock and roll roots he’d put aside to become a folk singer.

How to Truly Experience This Album Today

If you really want to understand why this record still hits, don't just stream it on shuffle. You have to treat it like a journey from the noise to the silence.

- Listen to it on Vinyl if you can. The split between Side A (Electric) and Side B (Acoustic) is essential to the pacing. That physical act of flipping the record gives you a moment to breathe before the heavy poetry of the second half starts.

- Watch 'Dont Look Back'. D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary of Dylan’s 1965 UK tour is the perfect companion piece. It shows the sheer arrogance and brilliance of Dylan during this exact window of time.

- Read the lyrics while listening. Especially for "It's Alright, Ma." The internal rhyme schemes are so complex that you’ll miss half of them if you’re just listening casually.

- Compare the "Subterranean" music video. It’s one of the first "music videos" ever—the one with the cue cards. It captures the "I don't care if you keep up" attitude of the whole era.

The real takeaway from Bob Dylan Bringing It All Back Home is that reinvention isn't just okay—it's necessary. Dylan taught us that an artist’s only obligation is to their own internal muse, not the expectations of the crowd. Whether you're a musician, a writer, or just someone trying to figure out their own path, there's a certain freedom in hearing Dylan laugh at his own mistakes on "115th Dream" and then immediately pivot into the most profound poetry of the 20th century.