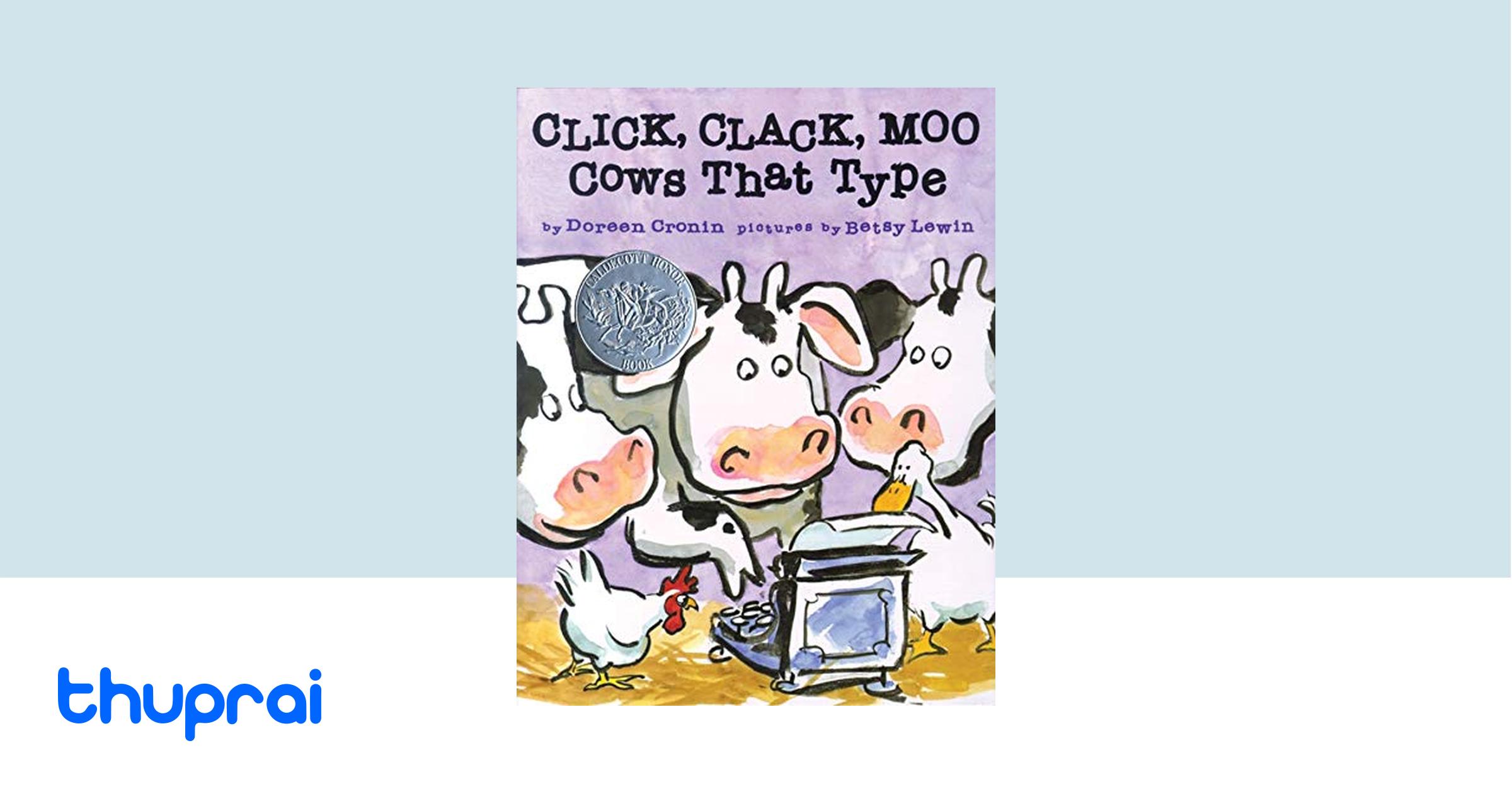

If you’ve spent any time around a preschooler or a primary school library in the last quarter-century, you know the sound. It’s the rhythmic, percussive cadence of a Remington. Or maybe an old Underwood. It’s the sound of a labor strike starting in a barn. Honestly, when Doreen Cronin released Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type back in 2000, nobody expected a picture book about bovine collective bargaining to become a permanent cultural fixture. But here we are. It’s a classic.

The premise is basically absurd. Farmer Brown has a problem: his cows found an old typewriter in the barn. Instead of sleeping, they’re typing. They have demands. It starts with electric blankets because, apparently, the barn is too cold. When the farmer says no, the cows go on strike. No milk. Then the hens join in. No eggs. It’s a quintessential standoff.

📖 Related: Power Book 2 stream: Why Everyone Is Still Looking for Tariq St. Patrick

What’s wild is how well this holds up. You’d think a book centered on a piece of obsolete technology like a manual typewriter would confuse kids born in the era of the iPad. It doesn’t. There is something inherently funny about the "click, clack" sound that Betsy Lewin’s watercolor illustrations capture so perfectly. It’s tactile. It’s noisy.

The Weird History of Farmer Brown’s Nemesis

Doreen Cronin wasn't actually a full-time children's author when she wrote this. She was a lawyer. You can tell. The way the cows frame their arguments—short, concise, and incredibly firm—reads like a well-drafted legal brief. "The barn is very cold. We’d like some electric blankets. Sincerely, The Cows." It’s a masterpiece of economy.

Most people don't realize that Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type was rejected by every major publisher for years. It sat in a drawer. When it finally got picked up by Simon & Schuster, it didn't just sell; it became a Caldecott Honor book in 2001. The industry was shocked. Why did a book about cows demanding better working conditions resonate?

Maybe because it’s the first time many kids encounter the concept of a "negotiation."

There's a specific tension in the plot. Farmer Brown isn't a villain, really. He's just a guy trying to run a farm. But the cows? They have the leverage. They know that without them, the whole operation falls apart. It's a heavy theme for a book aimed at five-year-olds, yet it’s handled with such a light touch that you barely notice the political undertones. It’s just funny. The cows are literate, and the farmer is furious.

Why the Typewriter Works Better Than a Smartphone

Imagine if the cows had found a MacBook. It wouldn't work. The "click, clack" is the heartbeat of the story. The physical act of typing—the hammer hitting the ribbon, the carriage return, the "moo" at the end of the line—creates a rhythm that makes it an elite read-aloud book.

If you’re reading this to a kid, you have to do the voices. You have to do the "click, clack, moo" with a specific cadence. If it were "tap, tap, text," the magic would vanish. The typewriter represents a bridge between the animal world and the human world. It’s a tool of communication that requires force. You have to want to say something to use a typewriter.

💡 You might also like: Jordan Peterson Piers Morgan Crying: What Really Happened Behind the Viral Tears

Duck: The Ultimate Neutral Party

We have to talk about the Duck.

Duck is the MVP of the "Click, Clack" universe. He’s the neutral party. He’s the one who brings the ultimatum to the barn door. But Duck is also a bit of a grifter. In the end, when the cows and the farmer finally reach a deal—the typewriter in exchange for electric blankets—Duck is the one tasked with delivering the typewriter.

He doesn't deliver it.

The book ends with a note from the ducks: "The pond is quite boring. We’d like a diving board. Sincerely, The Ducks." Then, the final sound effect: Click, clack, quack. It’s a perfect punchline. It suggests that once the door to communication (and demands) is open, you can’t really close it.

The E-E-A-T Factor: Why Educators Obsess Over This Book

Teachers love this thing. I’ve talked to dozens of literacy specialists who use Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type to teach "persuasive writing." It is the gold standard for that specific curriculum goal.

- It shows a clear "Problem and Solution" structure.

- It introduces the idea of an audience (Farmer Brown).

- It demonstrates the power of the written word.

According to literacy experts at organizations like Reading Is Fundamental (RIF), the book is also a prime example of "onomatopoeia" in practice. The repetition helps with phonics. But beyond the technical stuff, it’s the nuance of the conflict that matters. There’s no "bad guy." There is just a conflict of interest solved through a (somewhat) peaceful exchange.

The watercolor style of Betsy Lewin also deserves a deep look. She used loose, gestural lines. The cows aren't realistic; they’re expressive. You can see the indignation in their faces. This visual storytelling is why it stays on the "Best Sellers" lists for decades. It doesn't look dated because it never tried to look "modern."

📖 Related: Wonka and the Chocolate Factory Full Movie: What Most People Get Wrong

Common Misconceptions About the Series

Some folks think this was a standalone. Not even close. Cronin and Lewin built a massive franchise off this. You’ve got:

- Giggle, Giggle, Quack (The sequel where the Duck takes over).

- Dooby Dooby Moo (The cows enter a talent show).

- Click, Clack, Peep (A new chick arrives).

But honestly? None of them quite hit the heights of the original. The first book is pure. It’s a tight, 32-page explosion of logic and absurdity. Some parents worry the book "teaches kids to be defiant." That’s a bit of a stretch. It teaches kids that if you have a problem, you should write it down and present it clearly. That’s just good life advice.

What Really Happened With the Animated Version?

In 2006, the book was adapted into a short animated film narrated by Randy Travis. It’s actually quite good. It kept the spirit of the watercolors. Most "book-to-screen" adaptations for kids lose the soul of the source material by adding too much fluff. This one didn't. It leaned into the music.

If you’re looking for the best way to experience the story, the physical book is still king. There’s a specific joy in turning the page to see a giant "NO MILK. NO EGGS." sign posted on the barn door.

Putting the Lessons Into Practice

If you're a parent or a teacher, you can actually use the "Click, Clack, Moo" method to handle household or classroom issues.

- The "Sincerely" Rule: Encourage kids to write letters when they want something. It forces them to move past the "I want it now" tantrum and into the "Here is why I want it" phase.

- The "Fair Trade" Concept: The cows didn't just steal the blankets. They traded the typewriter. It teaches the concept of the "middle ground."

- Observe the Duck: Teach kids that sometimes, the person who seems to be helping is actually just looking for their own "diving board."

The legacy of these typing cows isn't just in the laughs. It’s in the fact that it respects a child’s intelligence. It assumes they can understand a stalemate. It assumes they find the idea of a typing cow as hilarious as we do.

To get the most out of this story today, look for the 20th Anniversary editions. They often include notes on how the book was developed and the original sketches that Lewin created before settling on the iconic look of the cows. Understanding the "why" behind the art makes the "click, clack" sound even more satisfying.

Next time you hear someone complaining about their working conditions, just remember: it could be worse. They could be a farmer with a cow who has a penchant for vintage office equipment and a cold barn.

Practical Next Steps for Fans:

- Check your local library for the "Click, Clack, Moo" sequels to see how the Duck's arc develops.

- Use the book as a starting point for a "persuasive letter" activity with kids—have them write a letter to "Farmer Mom" or "Farmer Dad."

- Look up the Caldecott Honor list from 2001 to see the other titles that defined that era of children's literature.