You know that specific, heavy smell of a September issue? It's thick. It’s a cocktail of glossy paper ink and about twelve different scents fighting for dominance. If you’ve ever flipped through GQ, Esquire, or Vogue, you’ve encountered them: the scent strips. They’re the slightly tacky, fold-over flaps that release a blast of "Oceanic Musk" or "Midnight Suede" the second you peel them back. For decades, cologne ads in magazines have been the gatekeepers of masculinity, telling us exactly what a "successful" man is supposed to smell like. But honestly, in an era where everyone is buying fragrances based on TikTok "deinfluencing" videos, you’d think these paper ads would be dead.

They aren't.

Actually, fragrance houses still spend millions on print. It's wild. You’d think a digital ad would be more efficient, right? But you can’t smell a smartphone screen. Not yet, anyway. The physical reality of a magazine page provides a sensory bridge that Instagram just can't cross.

The Psychology of the Scent Strip

The first thing to understand about cologne ads in magazines is that they aren't really about the smell. Or at least, not only the smell. They are about aspiration. Think about the imagery. You’ve got a guy like David Gandy or Chris Pine. They’re usually on a boat. Or leaning against a jagged rock in the Mediterranean. Maybe they're staring intensely at a camera while wearing a tuxedo that costs more than a used Honda Civic.

Brands like Giorgio Armani and Dior use these visuals to create a mental "vibe" before you even touch the scent strip. By the time you peel that paper back to smell Acqua di Giò, your brain has already associated the scent with sunlight, salt water, and effortless Italian luxury. It's a psychological trick called "priming."

📖 Related: Finding the Zip Code for Boston Massachusetts: It Is More Complicated Than You Think

The scent strip itself—technically known as a "ScentSeal"—was a massive technological breakthrough for the industry back in the late 1970s and early 80s. Before that, magazines were a mess. Perfume companies used to include actual liquid samples or "micro-encapsulated" beads that would get everywhere. It was gross. The ScentSeal changed the game by trapping the fragrance oils between layers of paper and adhesive. This keeps the scent fresh for months. It’s why a magazine from three years ago sitting in a doctor’s office might still have a faint whiff of Bleu de Chanel.

Does the Paper Actually Smell Like the Bottle?

This is where things get kinda tricky.

If you ask a fragrance purist, they'll tell you that cologne ads in magazines are a lie. They aren’t totally wrong. When you spray a fragrance from a glass bottle onto your skin, the scent evolves. You have the top notes (the stuff you smell immediately), the heart notes (the core of the scent), and the base notes (the heavy stuff like wood or musk that lasts all day).

On a magazine page, that evolution doesn't happen.

The scent strip gives you a "flat" version of the fragrance. It’s basically the middle and base notes frozen in time. Plus, the paper itself has a smell. The glue has a smell. If the magazine has been sitting in a hot mailbox, the fragrance oils might have degraded. So, when you smell a strip in Men’s Health, you’re getting a simplified, 2D version of the 3D experience. It’s like looking at a photo of a steak instead of actually eating one. It gives you the idea, but it’s not the whole story.

The Economics of the Page

Why do brands keep doing it? Because it works.

According to data from the Association of Magazine Media, print advertising still has a higher "brand recall" than digital ads. When you’re scrolling through a feed, you spend maybe 1.5 seconds on a post. When you’re sitting on a plane or in a waiting room with a magazine, you’re captive. You’re more likely to engage with the physical act of opening the flap.

The cost is astronomical. A single full-page ad in a major national magazine can cost upwards of $100,000. Add the cost of the fragrance sampling technology, and you’re looking at a massive investment. Only the big players can afford this. That’s why you see the same five brands—Chanel, Dior, Armani, Ralph Lauren, and Paco Rabanne—dominating the pages. It’s a way of signaling power. If a brand can afford a scent strip in the September issue of Vogue, they’re "legit."

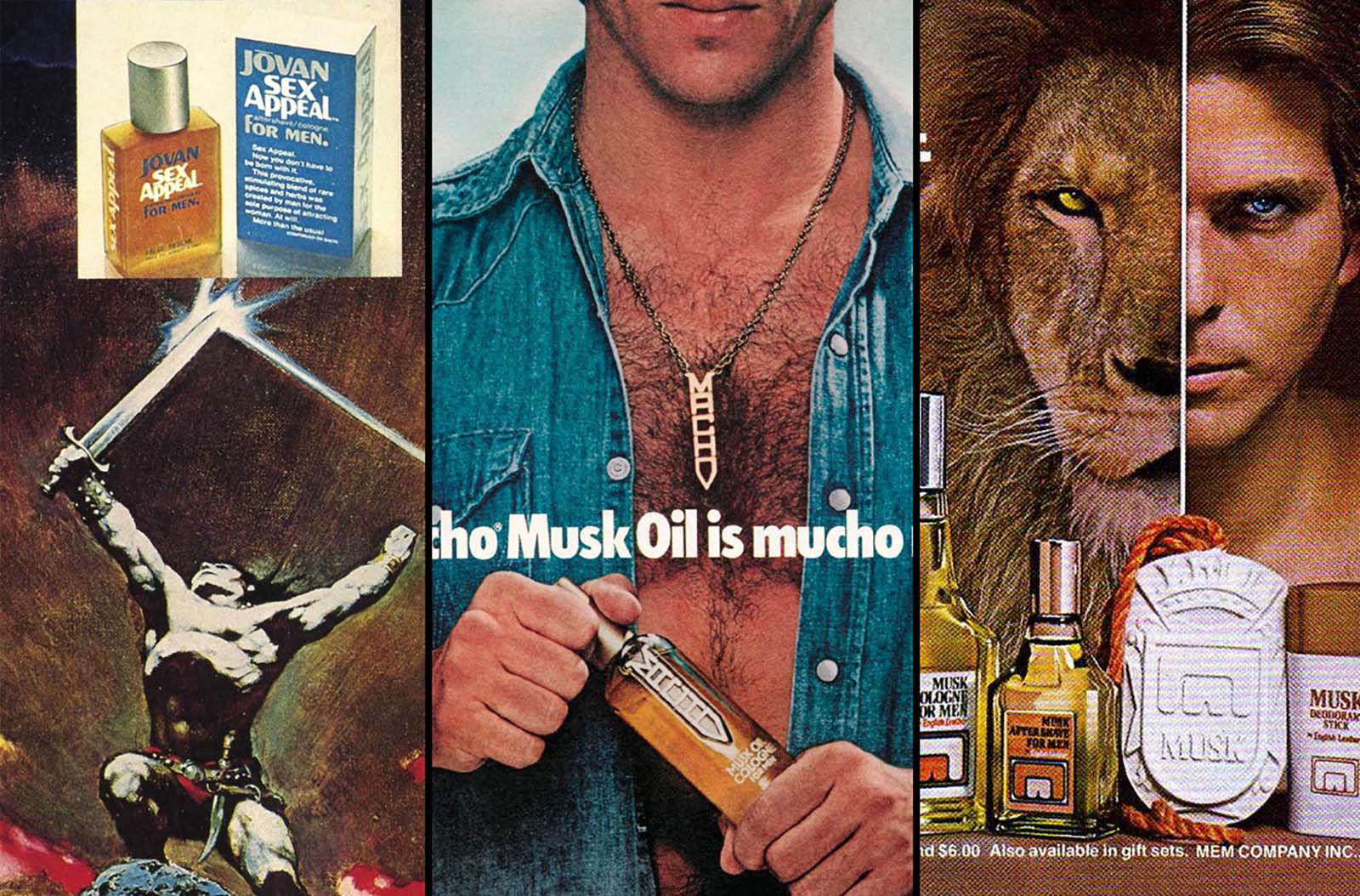

The Iconography of Masculinity

The visuals in these ads are fascinating if you really look at them. They’ve barely changed in forty years. You usually have one of three archetypes:

- The Explorer: This guy is always on a rugged coast or in a desert. Think Johnny Depp for Sauvage. It’s all about "raw" nature and "untamed" spirits.

- The Modern Aristocrat: This guy is in a suit. He’s in a penthouse or a classic car. It’s about wealth, status, and precision. Brands like Tom Ford nail this.

- The Athlete: Usually shirtless. Often wet. It’s about physical perfection and "sport" versions of scents. Polo Sport basically invented this entire genre in the 90s.

These ads aren't just selling a smell; they're selling a costume. When a guy buys the cologne, he’s buying a piece of that imagery. He wants to feel like the guy on the boat, even if he’s actually just sitting in a cubicle in Scranton.

📖 Related: Where Was Franz Ferdinand From: The Truth About the Man Who Started World War I

The Shift to "Niche" and the Decline of Print

We have to acknowledge the elephant in the room. Print media is struggling. Circulation numbers for many major magazines have plummeted over the last decade. As a result, the way we interact with cologne ads in magazines is changing.

Smaller "niche" brands—think Le Labo, Byredo, or DS & Durga—almost never use scent strips. They can’t afford them, and they don’t want to. They rely on "discovery sets" that they sell directly to consumers online. This has created a divide in the fragrance world. You have the "designer" scents that you find in magazines, which are designed to appeal to the widest possible audience, and the "niche" scents that thrive on exclusivity and social media buzz.

Interestingly, some high-end magazines like Fantastic Man or Monocle have experimented with more artistic ways of presenting fragrance, using better paper stock or even scented inks that aren't hidden behind a flap. It’s a more "premium" experience for a more "premium" reader.

How to Actually Use Magazine Ads to Find Your Scent

If you’re actually using these ads to shop, you need a strategy. Don't just smell the paper and run to the store.

First, treat the magazine ad as a "vibe check." If you hate the imagery and the scent on the paper smells like a cleaning product, skip it. But if the paper scent interests you, that’s your cue to go to a physical store.

You need to get the liquid on your skin.

Fragrance chemistry is weird. A scent that smells like "fresh laundry" on one guy might smell like "sour metallic" on another because of skin pH and oils. Always give a fragrance at least four hours on your wrist before you decide to buy it. The "dry down"—the way it smells after the initial alcohol blast fades—is what you’ll actually be living with.

The Environmental Impact

One thing people often overlook is the waste. Those scent strips make magazines harder to recycle. The adhesives and the concentrated oils can contaminate the paper recycling stream. Some environmental groups have pushed for brands to move toward digital sampling—where you scan a QR code to have a tiny vial mailed to your house—but the "instant gratification" of the peel-and-smiff is hard to beat.

The Future of Scent in Media

Where do we go from here?

We’re starting to see some wild stuff with haptic technology and "scent-tech." There are startups working on "digital noses" and devices that can emit specific scent molecules from a small attachment on your phone. But honestly? It feels a bit gimmicky.

There’s something timeless about the magazine ad. It’s a piece of physical art. In a world where everything is ephemeral and disappears with a swipe, the weight of a magazine page and the physical release of a scent feel substantial. It’s a tactile experience that grounds us.

Even if you never buy the cologne, there’s a comfort in the ritual. Flipping the page, seeing the moody black-and-white photography, and catching that whiff of something expensive. It’s a tiny, free luxury in a world that’s increasingly digital and sterile.

What to do next

If you're tired of the same old designer scents you see in every magazine, your next move is to look into "Sample Subscriptions" or "Discovery Sets." Most major fragrance houses and even niche boutiques now offer boxes with 5-10 tiny spray vials for about $30. It’s a much better way to test a scent than a piece of paper. You get to wear it for a few days, see how it reacts to your body heat, and find out if it actually gives you a headache after an hour.

Go to a high-end department store and ask for samples. Most sales associates at places like Nordstrom or Saks will give you a few vials if you’re genuinely interested. It’s a more accurate way to build a "scent wardrobe" than relying on the September issue.

Stop buying "blind." Use the magazine ads for inspiration, but let your own skin make the final decision.

Check your local specialty perfume shop. They often have brands you’ve never heard of that smell way more interesting than the "Blue" fragrances dominating the magazine pages right now. Look for notes like vetiver, sandalwood, or neroli if you want something that stands out from the typical "fresh" crowd.

Find a scent that feels like you, not just the guy on the boat.