Walk through Pueblo, Colorado today and you'll see the skeletons of a giant. It’s impossible to miss the sprawling Minnequa Works. For over a century, Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I) wasn't just a company; it was the entire economy of the Rocky Mountain West. It was the only integrated steel mill west of the Mississippi River. It built the rails that tamed the frontier. But it also broke the backs of thousands of immigrants and became the face of one of the darkest chapters in American labor history.

Honestly, most people today just think of it as a rusty landmark off I-25. That's a mistake.

The story of CF&I is basically the story of how the American West was industrialized. It’s a tale of massive wealth, brutal corporate warfare, and a family name—Rockefeller—that still triggers strong reactions in southern Colorado. You can’t understand the modern labor movement without looking at what happened in the coal canyons of Las Animas and Huerfano counties.

The Rise of a Western Monopoly

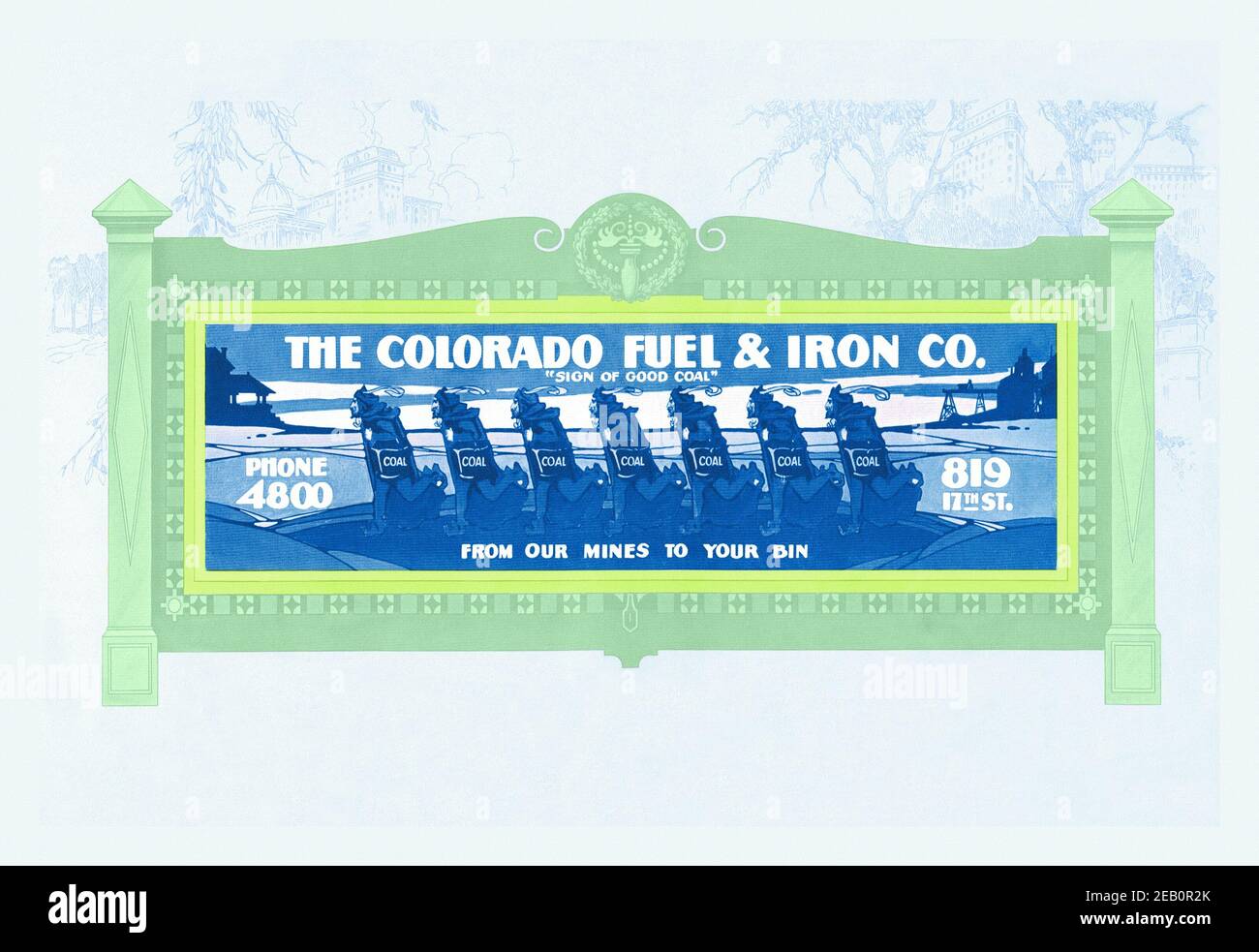

CF&I didn't start as a monolith. In 1892, a merger between the Colorado Coal and Iron Company and the Colorado Fuel Company created the beast we know today. John C. Osgood was the guy behind the wheel early on. He was ambitious. He wanted to compete with the steel titans of the East, like Carnegie and Schwab. And for a while, it worked. Pueblo became the "Pittsburgh of the West." Smoke billowed from the stacks. The city’s population exploded with workers from Italy, Greece, Mexico, and Slovenia.

It was a melting pot. But a high-pressure one.

By 1903, the Rockefellers took control. John D. Rockefeller Jr. saw CF&I as a vital piece of the family's empire. This changed the vibe. Management became more distant, more focused on the bottom line, and increasingly paranoid about the growing influence of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). The company owned everything. They owned the mines. They owned the houses the miners lived in. They owned the stores where the miners bought their food.

If you've ever heard the song "16 Tons," you know the deal. "I owe my soul to the company store." That wasn't just a catchy lyric for CF&I employees. It was reality.

What Actually Happened at Ludlow

You can't talk about Colorado Fuel and Iron without talking about the Ludlow Massacre. This is where the "expert" history gets heavy. In September 1913, thousands of miners went on strike. They wanted better pay, sure, but they also wanted the right to live where they chose and shop where they wanted. They wanted the company to actually obey Colorado's state mining laws, which were being ignored.

When the miners were evicted from company housing, they set up tent colonies. Ludlow was the biggest.

The winter of 1913-1914 was brutal. Tensions boiled over. The Colorado National Guard, which was essentially being bankrolled by CF&I at the time, moved in. On April 20, 1914, a day-long gun battle ended in fire. The tents went up in flames. Eleven children and two women suffocated in a "death pit" dug under a tent to hide from the bullets.

It was a PR disaster for the Rockefellers.

John D. Rockefeller Jr. was grilled by Congress. He claimed he knew nothing about the day-to-day operations, but the paper trail suggested otherwise. This event actually changed how American corporations handled PR. Rockefeller hired Ivy Lee—one of the fathers of modern public relations—to fix his image. This led to the "Rockefeller Plan," a sort of precursor to modern human resources, which gave workers a "voice" without actually giving them a union. It was clever. It was also a way to keep the UMWA out for another two decades.

The Steel Side of the Story

While the coal mines were a battlefield, the Minnequa Works in Pueblo were humming. CF&I was the backbone of the region's infrastructure. If you're walking on old railroad tracks anywhere in the Western US or even parts of Mexico, look at the stamp on the rail. There’s a good chance it says "CF&I" with a date from the 1920s or 40s.

They made more than just rails.

- Seamless pipe for the oil industry.

- Wire fencing that carved up the Great Plains.

- Grinding balls for the mining industry.

- Nails, bolts, and structural steel for skyscrapers.

The diversity of their product line kept them alive when other mills folded. During World War II, the plant was a 24/7 machine. It was essential for the war effort. Thousands of women entered the workforce at the mill, taking on jobs traditionally held by men who were off fighting. This period was the peak of CF&I’s economic power. Pueblo was a thriving, gritty, blue-collar hub.

The Long Decline and the EVRAZ Era

Nothing lasts forever. Especially not 19th-century industrial models. By the 1970s and 80s, the American steel industry was catching a beating. Foreign competition was cheaper. Technology was changing. CF&I was slow to adapt. The company went through a series of painful bankruptcies and ownership changes.

In 1993, Oregon Steel Mills bought the assets. Then came the Russian era. EVRAZ, a global steel and mining giant, eventually took over the Pueblo operations.

It's weirdly poetic. A company that helped build the American West is now owned by a multinational corporation. But the mill is still there. It’s no longer "Colorado Fuel and Iron" in name, but everyone in Pueblo still calls it "The Mill." They’ve pivoted. Today, they focus heavily on recycling scrap steel and producing rail. In fact, they recently opened a massive new solar-powered rail mill. It's one of the first in the world to be powered primarily by renewable energy.

👉 See also: Krispy Kreme Dunked On: Why the Internet Keeps Attacking the Glazed Giant

The irony is thick. The company that literally fueled the coal-driven industrial revolution is now using the sun to melt down old cars and turn them into tracks for modern trains.

Common Misconceptions About CF&I

People get a lot of things wrong about this company.

First, there's a belief that they were "just" a mining company. They were an "integrated" company, meaning they controlled the process from the dirt to the finished product. They mined the coal and iron ore, transported it on their own subsidiary railroads, and processed it in their own mills. This level of vertical integration was terrifying to regulators back then.

Second, folks often think the Ludlow Massacre ended the company. It didn't. It actually ushered in a period of paternalism where CF&I built YMCAs, schools, and hospitals to "civilize" the workforce. It was a control tactic, but it meant Pueblo had some of the best social facilities in the West for a time.

Third, there's a myth that the mill is a "dead" relic. It's not. It employs over a thousand people. It's still a massive player in the North American rail market. The scale has changed, but the impact hasn't.

Why You Should Care Today

If you're a business owner or a student of history, CF&I is a masterclass in corporate reputation management. They taught the world that you can't just ignore the "human element" of production—at least not without a massive cost.

The records of the company are now housed at the Steelworks Center of the West in Pueblo. It’s an incredible archive. They have over 100,000 photos and miles of documents. If you ever want to see the blueprints of how an empire is built—and how it nearly destroys itself—that's the place to go.

Practical Steps for Exploring the History of CF&I:

- Visit the Steelworks Center of the West: This isn't a boring museum. It's located in the old CF&I medical dispensary. You can see the actual medical equipment used on injured workers and the massive maps of the mine networks.

- Drive to the Ludlow Monument: It’s located about 15 miles north of Trinidad, Colorado. Stand there. It’s a quiet, eerie place. It helps you realize that the labor rights we take for granted—like the eight-hour workday—were paid for in blood right there on that prairie.

- Check the Rails: Next time you’re near a train track (safely!), look for the manufacturer's mark. Seeing "CF&I 1952" or "CF&I 1928" connects the abstract history to the physical world beneath your feet.

- Read "Out of the Depths" by Barron B. Beshoar: If you want the gritty, non-sanitized version of the Colorado Coalfield War, this is the book. It’s a classic of Western history.

The legacy of Colorado Fuel and Iron is complicated. It's a mix of incredible engineering, immigrant grit, and corporate ruthlessness. It built the West, but it also left deep scars. Understanding those scars is the only way to understand why the industrial landscape of Colorado looks the way it does today.