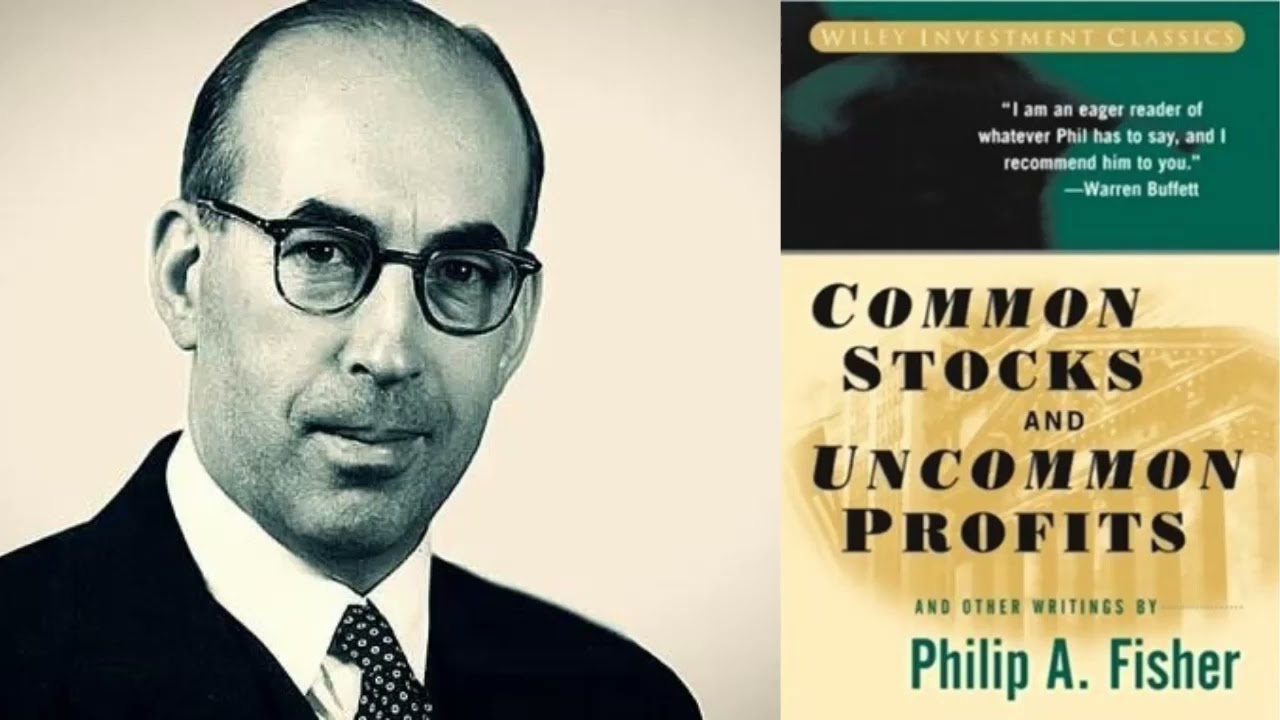

Philip Fisher was kinda the original "growth guy." Before him, everyone was obsessed with Ben Graham’s cigars butts—buying dying companies just because they were cheap. Fisher changed that. He didn't care about a company's past; he cared about where it was going. If you’ve ever wondered why Warren Buffett says he’s 15% Fisher and 85% Graham, you’re looking at the right book. Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits isn't just a manual; it’s a mindset shift that most retail investors still haven't quite figured out.

Investments aren't just tickers. They are living, breathing businesses. Fisher understood this better than almost anyone in the 1950s. He focused on the qualitative. He wanted to know if the managers were honest or if the R&D department was actually producing anything useful. It sounds simple. It isn't.

The Scuttlebutt Method: How Fisher Actually Found Winners

Most people today sit behind a Bloomberg terminal or a Robinhood app and think they’re "researching." Fisher would have laughed at that. He pioneered the "Scuttlebutt" method. Basically, he went out and talked to people. He talked to competitors, ex-employees, and suppliers. He wanted the dirt.

Imagine you're looking at a tech company today. A standard analyst looks at the P/E ratio. A Fisher disciple? They’re checking Glassdoor to see if the engineers hate the CTO. They’re calling up vendors to see if the company pays its bills on time. Fisher believed that if you talk to enough people, a clear picture of the company’s "DNA" starts to emerge. You find out things the annual report will never tell you.

💡 You might also like: Highest dividend paying stocks in world: Why yield isn't everything in 2026

He had this checklist. 15 points. But it wasn't a "check the box and buy" type of deal. It was a framework. He wanted "superior sales and marketing." He wanted a company that could grow its sales for years without needing to constantly ask shareholders for more cash. He looked for high profit margins because, honestly, if a company has thin margins, one bad quarter can wipe them out. Fisher wanted a safety net of efficiency.

The 15 Points: What Most People Get Wrong

People often skim the 15 points in Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits and think they’ve got it. They don't. Point number two, for instance, is about management’s determination to continue to develop products. This is huge. A lot of companies have one "hit" and then coast. Think about the companies that dominated 2010 but are ghosts now. They stopped innovating.

Fisher didn't want the one-hit wonders. He wanted the compounding machines.

Why R&D is a Trap for Amateurs

Fisher was obsessed with Research and Development. But he wasn't just looking at the dollar amount spent. He looked at the effectiveness of that spend. If a company spends a billion dollars on R&D but hasn't launched a successful product in five years, that’s a red flag. It’s a "black hole" for capital. He wanted to see a direct line between the lab and the bottom line.

The Management Factor

He also cared deeply about labor relations. This was radical for the time. In the 50s, most bosses viewed workers as interchangeable parts. Fisher saw them as an asset. He argued that if a company has bad relations with its workers, it’s going to have strikes, low productivity, and high turnover. That costs money. Real money. It’s an "uncommon" insight because it’s hard to quantify on a spreadsheet, but it shows up in the stock price eventually.

💡 You might also like: The Lafayette Square Mall Story: What Really Happened to This Indy Landmark

When to Buy and (More Importantly) When Not to Sell

Fisher was a "buy and hold" extremist. He famously bought Motorola in 1955 and held it until his death in 2004. Think about that. Nearly 50 years. He saw the transition from vacuum tubes to transistors to cellular phones.

Most investors panic. They see a 20% drop and they bail. Fisher argued that if you’ve done your "scuttlebutt" correctly, the price fluctuations don't matter. In fact, he said the best time to sell a stock is "almost never."

There are only three reasons to sell, according to him:

- You made a massive mistake in your initial assessment.

- The company has changed (management got lazy, or the market moved past them).

- You found something even better (though this was rare for him).

He hated "dipping in and out." He thought it was a fool's errand. You've probably felt that itch to "lock in profits." Fisher would tell you to sit on your hands. If the business is still great, why would you want to own less of it?

The Fallacy of Diversification

Here’s where Fisher gets controversial. He didn't believe in owning 50 stocks. He thought that was "over-diversification." If you own 50 stocks, you can't possibly know enough about all of them to have an edge. You’re just buying the index at that point, but with higher fees.

Fisher preferred a "concentrated" portfolio. Five to ten great companies. That’s it. He believed that if you truly understand a business, you don't need the "safety" of 40 other stocks you barely understand. Of course, this requires massive balls. If one of those five goes to zero, you're hurting. But Fisher’s point was that if you do the work—the real scuttlebutt work—the odds of it going to zero are incredibly low.

The Modern Application: Is Fisher Still Relevant in 2026?

You might think a book written decades ago is useless in the age of AI and high-frequency trading. You’d be wrong. In fact, Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits is more relevant now because everyone else is looking at the same data.

The internet has democratized financial statements. Everyone has the P/E ratio. Everyone sees the quarterly earnings. The "alpha"—the extra profit—is now found in the things the internet doesn't show. The qualitative stuff. The "vibes" of the management team. The way they handle a crisis.

Look at how Nvidia or Tesla are discussed. The people who made the most money weren't the ones looking at the 2018 P/E ratios. They were the ones who saw the "uncommon" potential of the leadership and the tech stack. They were doing a version of Fisher's scuttlebutt.

Common Misconceptions About Fisher’s Strategy

A lot of people think Fisher was just a "growth at any price" guy. He wasn't. He was very sensitive to price, but he just didn't think the P/E ratio was the best way to measure it. He’d rather pay a "high" price for a legendary company than a "low" price for a mediocre one.

📖 Related: How Can I Get My Money Back From a Scammer? What Actually Works

"I don't want a lot of good investments; I want a few outstanding ones." That was his mantra.

Another misconception is that his style is "easy." It's actually much harder than Graham’s value investing. Finding a "cheap" stock is a math problem. Finding an "outstanding" company is an investigation. It requires talking to people, visiting factories, and deeply understanding industry trends. It’s exhausting work.

Actionable Steps for Your Portfolio

If you want to start investing like Philip Fisher today, you can't just buy a "Growth ETF" and call it a day. You have to get your hands dirty.

- Pick three companies you use every day. Don't look at their stock price yet. Look at their products. Are they getting better? Do people love working there?

- Start your own Scuttlebutt. Read the "Risk Factors" section of the 10-K, but then go deeper. Look for interviews with former employees. Watch how the CEO handles tough questions from journalists, not just the "softball" questions on earnings calls.

- Check the "integrity" of management. This is Point 15. Do they tell the truth when things go wrong? Or do they blame "macroeconomic headwinds" every time they miss a target? Honest management is a prerequisite for uncommon profits.

- Audit your R&D. If you're investing in tech or pharma, look at the pipeline. Is the company inventing new things, or just acquiring smaller companies to hide their own lack of innovation?

- Commit to the long haul. If you aren't willing to hold the stock for five years, don't hold it for five minutes. This forces you to be much more selective about what you buy.

Fisher’s approach isn't about getting rich quick. It’s about not being average. It’s about finding those rare, generational companies that change the world and having the courage to hold onto them while everyone else is trading "noise." It’s about the uncommon discipline to ignore the crowd and focus on the business.

Invest in the business, not the ticker. That’s the secret.

Next Steps for Implementation:

To apply Fisher's logic to your current holdings, perform a "Reverse Scuttlebutt." Search for the most vocal critics of a company you own. If their arguments are based on temporary issues (like a bad quarter), ignore them. If they point to a fundamental decay in management integrity or product quality (Point 15 or Point 2), it's time to re-evaluate your position regardless of the current stock price.