You’d probably guess that doctors or maybe high-stakes Wall Street traders have the toughest time keeping it together. It makes sense, right? Those jobs are basically pressure cookers. But if you actually look at the data—real numbers from the CDC and the Bureau of Labor Statistics—the reality is a lot more grounded and, honestly, quite a bit grittier.

When people ask what profession has the highest rate of suicide, they often expect a white-collar answer. But for years, the "Construction and Extraction" industry has consistently sat at the very top of that grim list. According to the most recent deep dives into mortality data, construction workers are dying by suicide at a rate nearly four to five times higher than the rate of fatal work-related injuries in the same industry. Think about that. We spend billions on hard hats and fall protection, but the biggest killer on the job site isn't a fall from a ladder. It's the stuff happening inside a worker's head.

Breaking Down the Numbers: Construction and Beyond

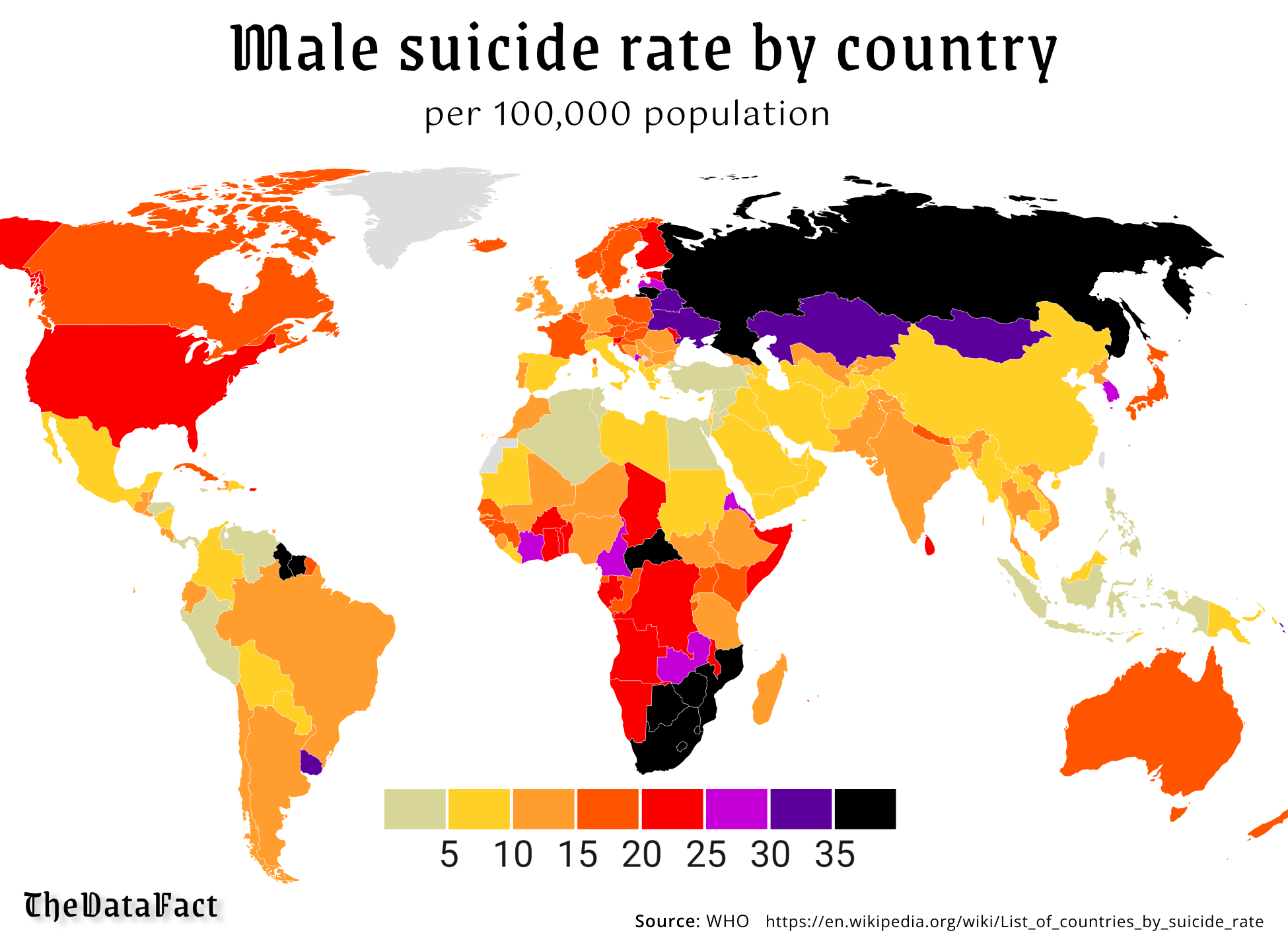

Basically, we're looking at a rate of roughly 65 to 69 deaths per 100,000 for men in construction and extraction. To put that in perspective, the average across all civilian occupations is usually closer to 15 or 16 per 100,000. It's a massive, staggering gap.

But it’s not just the guys swinging hammers. Other industries are struggling too:

- Mining and Quarrying: Often trades the #1 spot with construction depending on the year.

- Installation, Maintenance, and Repair: Think of the people fixing your HVAC or working on power lines.

- Farming, Fishing, and Forestry: Extreme isolation and financial instability play a huge role here.

- Protective Services: This includes law enforcement and first responders who see the worst of humanity every single shift.

What’s interesting is how it shifts by gender. For men, the "tough guy" industries like construction and mining are the deadliest. For women, the data often points toward "Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports, and Media" or "Healthcare Support" roles as having the highest rates. It’s a complex web of accessibility to means, workplace culture, and sheer emotional burnout.

Why Is Construction So High?

It’s not just one thing. It’s a "perfect storm" of factors that hit all at once. First, you've got a workforce that is overwhelmingly male. Statistically, men are less likely to seek help for mental health and more likely to use lethal means. Then, you layer on the "tough it out" culture. On a job site, if you're hurting, you're often expected to just rub some dirt on it and keep moving. Vulnerability isn't exactly encouraged when you're surrounded by heavy machinery and tight deadlines.

Physical pain is another huge piece of the puzzle. Chronic injuries lead to opioid prescriptions. We know the link between the opioid crisis and suicide is direct and devastating. When the pills stop working or the prescription runs out, the mental toll of chronic pain can become unbearable. Add in seasonal work, long commutes, and being away from family for weeks at a time, and you have a recipe for extreme isolation.

📖 Related: Coffee Memorial Blood Center Amarillo: Why Giving Locally Actually Matters

The Role of "Access to Means"

One thing experts like those at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) always point out is how easy it is for someone to actually go through with it. In many of these high-rate professions, workers have ready access to lethal tools or substances. For a veterinarian, it’s pentobarbital. For a farmer or a police officer, it’s a firearm. In construction, the environment itself provides numerous ways to end a life.

Is it Getting Better?

Kinda. But slowly.

📖 Related: Ames Hospice Westlake Ohio: What Most Families Don’t Realize About Inpatient Care

For a long time, mental health wasn't even a conversation in the trades. Now, you’re starting to see things like "Construction Suicide Prevention Week" and "Toolbox Talks" that focus on brain health instead of just safety harnesses. Unions and big firms are starting to realize that losing their best workers to a preventable mental health crisis is both a tragedy and a massive business loss.

Actionable Steps for the Workplace

If you're in one of these high-risk fields—or you manage people who are—the "wait and see" approach is literally deadly. Here is how to actually move the needle:

- Change the Language: Stop saying "commit suicide." It sounds like a crime. Use "died by suicide." It’s a small shift, but it removes a layer of shame that keeps people from talking.

- Normalize the Struggle: Leaders need to be the ones to say, "Hey, I had a rough year and I talked to someone." When the boss says it’s okay to not be okay, the crew listens.

- Make Help Invisible: Ensure that Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) are truly anonymous and easy to access. If a worker thinks their supervisor will find out they called a therapist, they won't call.

- Training is Key: Programs like QPR (Question, Persuade, Refer) or the "LivingWorks" training specifically for workplaces can give regular people the skills to spot a crisis before it’s too late.

- Address Chronic Pain: Don't just treat the injury; treat the person. Managing physical pain through non-opioid means and physical therapy can prevent the downward spiral that often leads to a mental health crisis.

If you or someone you know is struggling, you don't have to be a statistic. In the US and Canada, you can call or text 988 anytime. It’s free, it’s confidential, and there’s a real person on the other end who actually gets it. The "tough guy" act has a ceiling, and honestly, reaching out is the gutsiest thing you can do.

Next Steps for You: Check your company's health insurance policy today to see exactly what mental health services are covered. Often, there are 5-10 free counseling sessions available through an EAP that no one ever uses because they don't know they exist. If you’re a manager, print out the 988 posters and put them in the breakroom or on the back of the porto-john doors—places where a worker can look at them privately. It sounds simple, but it’s often the only lifeline someone sees during their darkest hour.