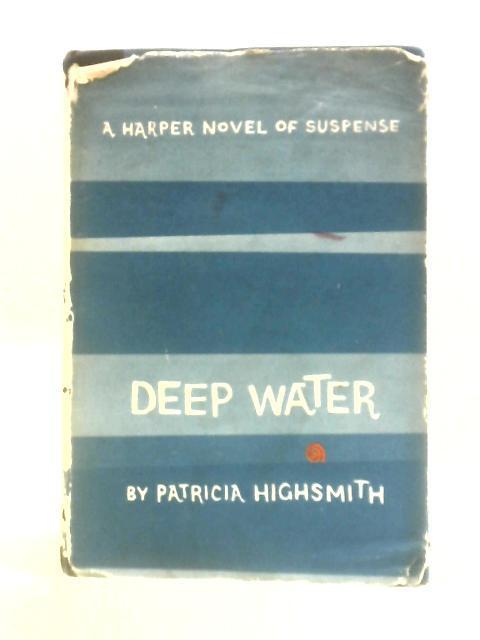

Patricia Highsmith was a bit of a misanthrope. That's not a secret. She liked snails more than people, and honestly, after reading a Deep Water Highsmith novel, you kinda start to see her point. Published in 1957, Deep Water isn't just a "thriller." It’s a slow-motion car crash of a marriage that feels uncomfortably modern despite the mid-century suburban setting of Little Wesley.

Most people know the story now because of the Ben Affleck and Ana de Armas movie, but the book? The book is a whole different beast. It’s meaner. It’s smarter. And it’s way more disturbing because Vic Van Allen isn't your typical psychopath. He’s the guy you’d actually want to have a drink with at a boring neighborhood party. Until you realize he's watching you.

The Domestic Terror of Vic Van Allen

Vic is "enlightened." At least, that’s what he tells himself. He’s a wealthy, intellectual man who runs a small press and loves his daughter, Trixie. His wife, Melinda, is... well, she's a lot. She’s bored, she’s drinking too much, and she’s constantly parading a string of "friends"—read: lovers—right in front of Vic’s face. In any other 1950s novel, the husband would be the hero or the victim. In a Deep Water Highsmith novel, those lines don't just blur; they disappear entirely.

Highsmith does something brilliant here. She makes us empathize with a killer. Vic decides to scare off Melinda’s latest fling by claiming he murdered her previous lover, Malcolm McRae. He didn't actually do it—not yet—but the lie works. It gives him power. It makes him interesting.

✨ Don't miss: Watching Friendly Rivalry Ep 5 Eng Sub: Why This Episode Changes Everything

The terrifying part isn't the murder. It’s the social pressure. The way the neighbors in Little Wesley watch, whisper, and judge. Highsmith captures that specific brand of suburban claustrophobia where everyone knows you're miserable, but no one wants to be the first to mention the blood on the carpet.

Why Highsmith Wrote Monsters So Well

She lived it. Patricia Highsmith wasn't exactly a ray of sunshine in her personal life. Biographers like Andrew Wilson, who wrote Beautiful Shadow, detail her obsession with the darker impulses of the human psyche. She didn't view her characters as "evil." She viewed them as logical.

If someone is ruining your life, why wouldn't you want them gone?

That’s the "Highsmith logic." It strips away the moralizing we usually see in crime fiction. There’s no detective like Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot coming to restore order. In Deep Water, the disorder is the point. The universe doesn't care about justice. It only cares about who is clever enough to survive.

🔗 Read more: Why Love Island Host Ariana Madix Actually Saved the Franchise

The Psychology of the "Cuckold" Narrative

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room. This book is fundamentally about a man being publicly humiliated by his wife's infidelity. But Vic doesn't react with rage. He reacts with a weird, cold detachment that is far more frightening.

He’s performing the role of the "good husband" while his mind is elsewhere.

- He tends to his snails.

- He prints fine editions of books.

- He makes cocktails for his wife's lovers.

It’s a performance. And that’s what makes a Deep Water Highsmith novel so effective for Google Discover readers today—we live in an era of curated identities. We all have a "Vic Van Allen" version of ourselves we present to the world while our inner lives might be a mess of resentment and weird hobbies.

The Snails: More Than Just a Quirk

If you’ve read the book, you know about the snails. Vic keeps them in the basement. He watches them mate and eat and move slowly across the glass. They are a mirror for the plot itself. Slow. Methodical. Slimy.

Highsmith herself was obsessed with snails. She reportedly once showed up to a party with a handbag full of them and a head of lettuce. By giving this trait to Vic, she’s giving him a piece of her own soul. The snails represent a world where things make sense, unlike the chaotic, emotional world Melinda inhabits. Vic prefers the cold, biological imperatives of his terrarium to the messy reality of his bedroom.

Where the Movies Usually Get It Wrong

The 2022 Adrian Lyne adaptation tried. It really did. But it added a level of eroticism that isn't really the focus of the book. In the Deep Water Highsmith novel, the sex isn't the point—the lack of it is. The vacuum where a relationship should be.

The 1981 French film Eaux profondes actually captures the vibe a bit better. It understands that this is a story about a man who is essentially "gaslighting" an entire town.

- He creates a persona of the long-suffering saint.

- He pushes Melinda until she looks like the "crazy" one.

- He uses the town's own politeness against them.

If you're looking for a hero, you're reading the wrong author. Highsmith doesn't do heroes. She does survivors and victims, and often they’re the same person.

The Turning Point: Charlie De Lisle

Everything changes when Charlie De Lisle enters the picture. He’s the one who doesn't play by the rules. He’s the one who makes Vic feel like he’s losing control of the narrative. When Vic finally snaps and drowns Charlie in a swimming pool during a party—hence the title—it’s not a moment of passion. It’s a housekeeping chore. He’s just taking out the trash.

✨ Don't miss: Why The Rookie Season 1 Episode 9 Stays The Show’s Most Relatable Hour

The way Highsmith describes the murder is chillingly matter-of-fact. No dramatic music. No grand monologues. Just a man holding another man underwater until the bubbles stop. It’s the banality of it that sticks with you.

How to Read Highsmith Without Losing Your Mind

If you're diving into the Deep Water Highsmith novel for the first time, don't expect a traditional mystery. You know who did it. The characters mostly know who did it. The suspense comes from wondering how long the "civilized" world can ignore the truth.

It’s a masterclass in tension.

You’ll find yourself rooting for Vic, then feeling disgusted with yourself for doing so. That’s the "Highsmith Trap." She forces you into the killer's head until his logic starts to sound... well, reasonable. "She shouldn't have pushed him," you might think. And then you realize you're justifying murder.

Actionable Insights for Fans of the Genre

If you finished Deep Water and need more of that specific, itchy feeling under your skin, here’s how to navigate the world of Highsmith and her contemporaries:

- Read "The Talented Mr. Ripley" next: If you liked Vic, you’ll love Tom Ripley. He’s the gold standard for the "charming sociopath."

- Look for the 1950s context: Understanding the rigid social expectations of the era makes Melinda’s rebellion and Vic’s repression much more impactful. It wasn't just a bad marriage; it was a failure of the American Dream.

- Watch the 1981 French adaptation: Seek out Eaux profondes (Deep Water) starring Isabelle Huppert. It captures the psychological warfare much better than the Hollywood versions.

- Check out Margaret Millar: If you like this brand of psychological suspense, Millar was a contemporary of Highsmith who wrote equally biting, twisty domestic thrillers like Beast in View.

- Analyze the "Snail" Metaphor: Next time you’re reading, pay attention to when the snails appear. They usually signal a moment where Vic is retreating from humanity into his own cold, calculated world.

Highsmith’s work persists because she wasn't afraid to be ugly. She didn't need her characters to be likable; she just needed them to be real. Deep Water remains one of her most potent works because it suggests that the person living next door to you—the one with the nice house and the quiet hobbies—might just be capable of anything if you push them far enough into the deep end.

Next Steps for Your Literary Journey

Go back and re-read the scenes involving the neighbors, specifically the characters of Don and Mary Nichols. Notice how they act as a "chorus," representing the public's willingness to turn a blind eye to obvious violence for the sake of social decorum. It’s a haunting reflection of how communities often protect "respectable" men at the expense of "difficult" women. Explore the correspondence of Patricia Highsmith at the Swiss Literary Archives if you want to see the real-life inspirations for her cold, detached prose style.