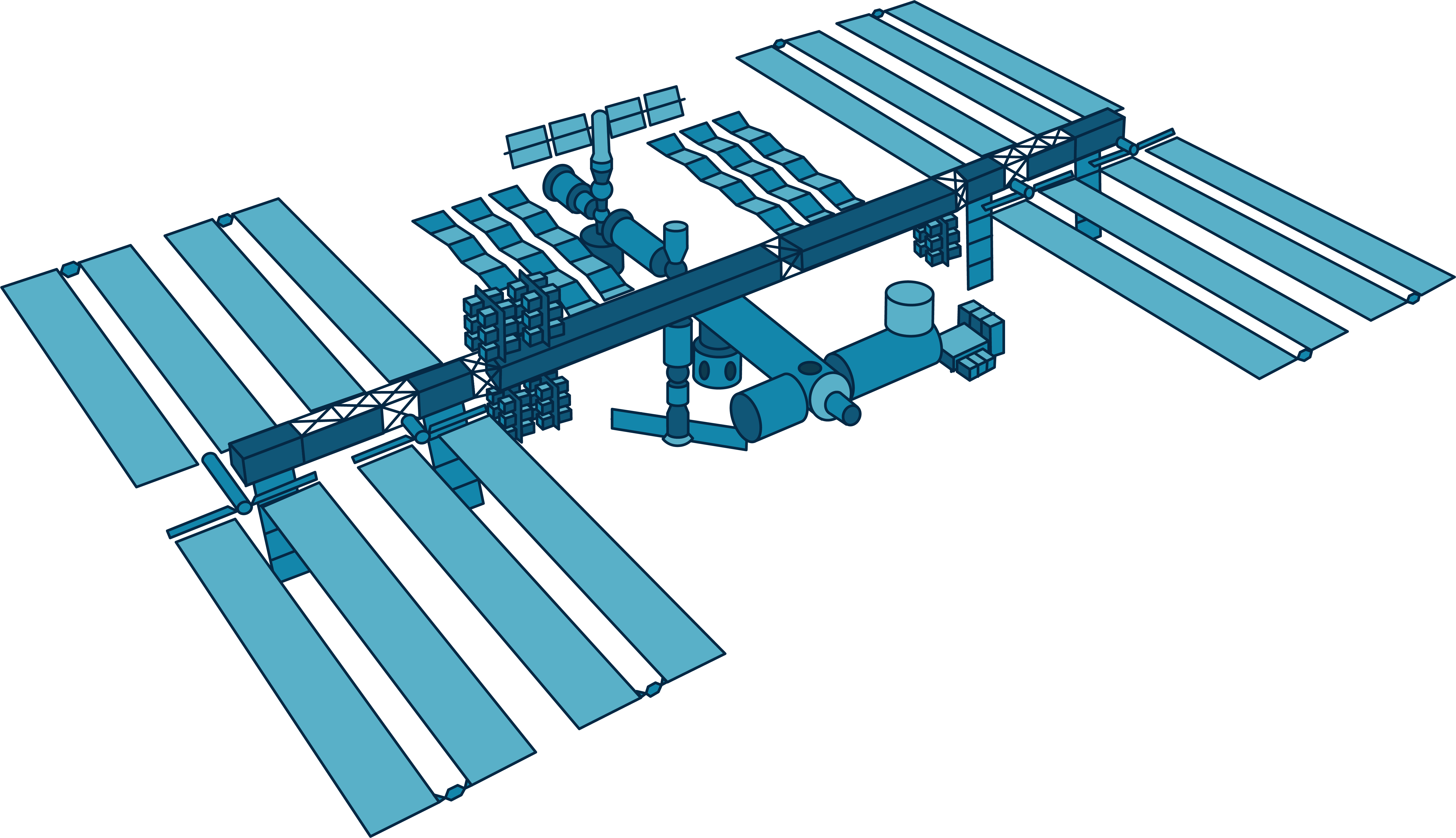

You’ve probably seen them on your feed. One day it’s a glowing, spider-webbed network of city lights from 250 miles up, and the next, it’s a crisp, almost clinical silhouette of the station itself transit across a massive, orange sun. But here is the thing about pics of the International Space Station: they aren't just one thing. Most people think "space photography" and imagine a giant telescope like Hubble or James Webb.

Nope.

The photos we see of the ISS—or from it—are actually a wild mix of high-end consumer Nikon DSLRs, specialized external tracking cameras, and even amateur gear from folks standing in their backyards in Ohio. It's kinda chaotic when you think about it. You have astronauts floating in the Cupola, trying to steady a camera while moving at 17,500 miles per hour, competing with ground-based photographers who use software to predict exactly when the station will zip past their lens for a fraction of a second.

The Gear Behind Those Unreal Orbital Shots

NASA doesn’t actually use some secret, alien camera technology to get those high-res shots of the station’s exterior. Honestly, they’re mostly using off-the-shelf Nikon bodies. For years, the D5 and the D6 have been the workhorses up there. They chose Nikon decades ago because the ergonomics work well with bulky EVA (Extravehicular Activity) gloves, and the glass is top-tier. When you see pics of the International Space Station during a spacewalk, you’re usually looking at a camera wrapped in a "thermal blanket"—essentially a white, quilted puffy jacket for the camera to keep the electronics from freezing or cooking in the extreme temperature swings of direct sunlight.

There's a specific challenge no one talks about: radiation.

Down here, we don't worry about cosmic rays hitting our camera sensors. Up there? It’s a constant barrage. Over time, the sensors on the ISS get "hot pixels"—tiny white or colored dots that stay stuck because a high-energy particle literally fried that part of the chip. This is why NASA cycles through gear. They don't just keep the same camera for ten years; they have to refresh the inventory as the hardware literally degrades from being in space.

The Cupola: The World’s Most Expensive Window Seat

If you’ve seen a photo where the Earth looks like a giant, curved marble and you can see the edge of a window frame, that was taken in the Cupola. It’s a seven-window observation module. It’s basically the "living room" of the ISS where astronauts go to decompress. Don Pettit, an astronaut known for being a bit of a photography wizard, famously used to "hack" his camera setups up there. He’d use spare parts to create barn-door trackers—basically DIY mounts—to cancel out the orbital motion so he could get those long-exposure city light shots without them turning into a blurry mess.

Without that tracking, the ground moves too fast for a sharp photo at night.

Spotting the Station from Your Own Backyard

Wait, you don't need to be an astronaut to get incredible pics of the International Space Station. In fact, some of the most viral images come from terrestrial photographers like Thierry Legault. He’s the guy who travels across the world just to stand in a specific spot for 0.5 seconds to catch the ISS crossing in front of a solar eclipse or the moon.

It takes a ridiculous amount of math.

Basically, the ISS is small—about the size of a football field—but it’s 250 miles away. To see it from Earth, you need high magnification. But because it’s moving so fast, you can’t just point and shoot. You use tools like "Transit Finder" or "Heavens-Above" to know exactly where to be. If you’re off by even a few hundred meters, you’ll miss the transit entirely.

- Use a tripod. No, seriously. You can't hand-hold a 600mm lens and expect a clear shot of a moving satellite.

- Fast shutter speeds are king. We’re talking 1/2000th of a second or faster to freeze the motion.

- Solar filters are non-negotiable if you’re shooting a solar transit. You’ll melt your sensor (and your eyes) otherwise.

Why the Colors Look Different in Every Photo

Have you noticed how some pics of the International Space Station look deep blue and crisp, while others look hazy or even slightly orange? It’s not just Photoshop. It’s the atmosphere.

When an astronaut takes a photo looking straight down (nadir), they are looking through the thinnest part of Earth's atmosphere. The colors are punchy and true. But when they take "limb" shots—looking toward the horizon—the light has to travel through hundreds of miles of air. This scatters the blue light, leaving the reds and oranges, which is why orbital sunsets look like a layered rainbow of fire.

Also, the station’s solar arrays are weirdly photogenic. They are made of thousands of solar cells covered in thin glass. Depending on the angle of the sun, they can look like bright gold, deep blue, or even pitch black. This "specular reflection" is why the ISS is often the brightest thing in the night sky, sometimes outshining Venus.

The Reality of Post-Processing in Space

NASA doesn't just "filter" things to make them look cool. They actually have a very strict protocol for the Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth (the official database). Most images you see are "raw" or have basic color correction to match what the human eye actually sees.

However, when you see those stunning time-lapses where the aurora borealis looks like a flowing green river, those are usually composite images. An editor on the ground takes hundreds of individual frames and stitches them together. They have to de-noise the images because, again, the radiation-damaged sensors create a lot of "salt and pepper" grain in the dark areas of the photos.

It’s a massive manual effort.

✨ Don't miss: Why Solar System and Planets Images Look Different Than You Think

Common Misconceptions About ISS Photos

I see this one a lot on Reddit: "Why can't you see stars in the background of ISS photos?"

It’s a simple photography thing called dynamic range. The ISS is a bright, white object reflecting direct, unfiltered sunlight. If you expose the camera so the station looks clear and not like a glowing white blob, the stars—which are much, much dimmer—simply won't show up. They are there; the camera just isn't "seeing" them because it’s tuned for the bright stuff. It’s the same reason you don’t see stars in photos of a football game at night, even though the sky is right there.

Another one: "The photos are fake because the Earth looks too curved."

That’s usually a result of using a wide-angle lens. To get the whole station in the frame from a short distance (like from a departing Soyuz or Crew Dragon), you need a wide lens. These lenses naturally distort the horizon. If you use a long telephoto lens from further away, the horizon looks much flatter. It’s just optics, not a conspiracy.

What’s Next for Space Photography?

We are moving away from the era of just "stills." With the arrival of 8K cameras on the station and the upcoming commercial modules from companies like Axiom, we are going to see a flood of ultra-high-definition video that makes current pics of the International Space Station look like Polaroids.

They are even testing "360-degree" cameras outside the station. Imagine putting on a VR headset and seeing exactly what an astronaut sees during an EVA, with the station's trusses stretching out behind you and the entire Earth spinning below. We are basically at the point where space photography is becoming an immersive experience rather than just a flat image on a screen.

✨ Don't miss: US Mobile eSIM Activation: Why Most People Get It Wrong

How to Find the Best ISS Images Yourself

If you want to move beyond the generic "top 10" lists and find the high-resolution stuff used by researchers, here is how you do it:

- Go to the Source: Bookmark the Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth. It’s a searchable database of over 1.5 million photos. You can search by "Long/Lat" or specific features like "volcanoes" or "hurricanes."

- Check the Metadata: If you find a photo on Flickr or NASA's official site, look for the EXIF data. It’ll tell you the lens used (usually a 400mm or 800mm for ground shots) and the shutter speed. This is the best way to learn how to replicate the look.

- Track the Transit: Download an app like "ISS Detector." It will alert you when the station is passing over your house. If it’s right after sunset or before sunrise, the station will be illuminated while you are in the dark, making it look like a bright, fast-moving star.

- Follow the Astronauts: Honestly, their personal X (Twitter) or Instagram accounts are where the "raw" and "fun" shots end up first. Guys like Thomas Pesquet or Matthew Dominick often share the technical details of how they captured a specific lighting effect.

The ISS won't be up there forever. Current plans have it de-orbiting sometime around 2030. Every photo captured now is a historical record of the most complex machine humans have ever built, floating in the most hostile environment we’ve ever explored.