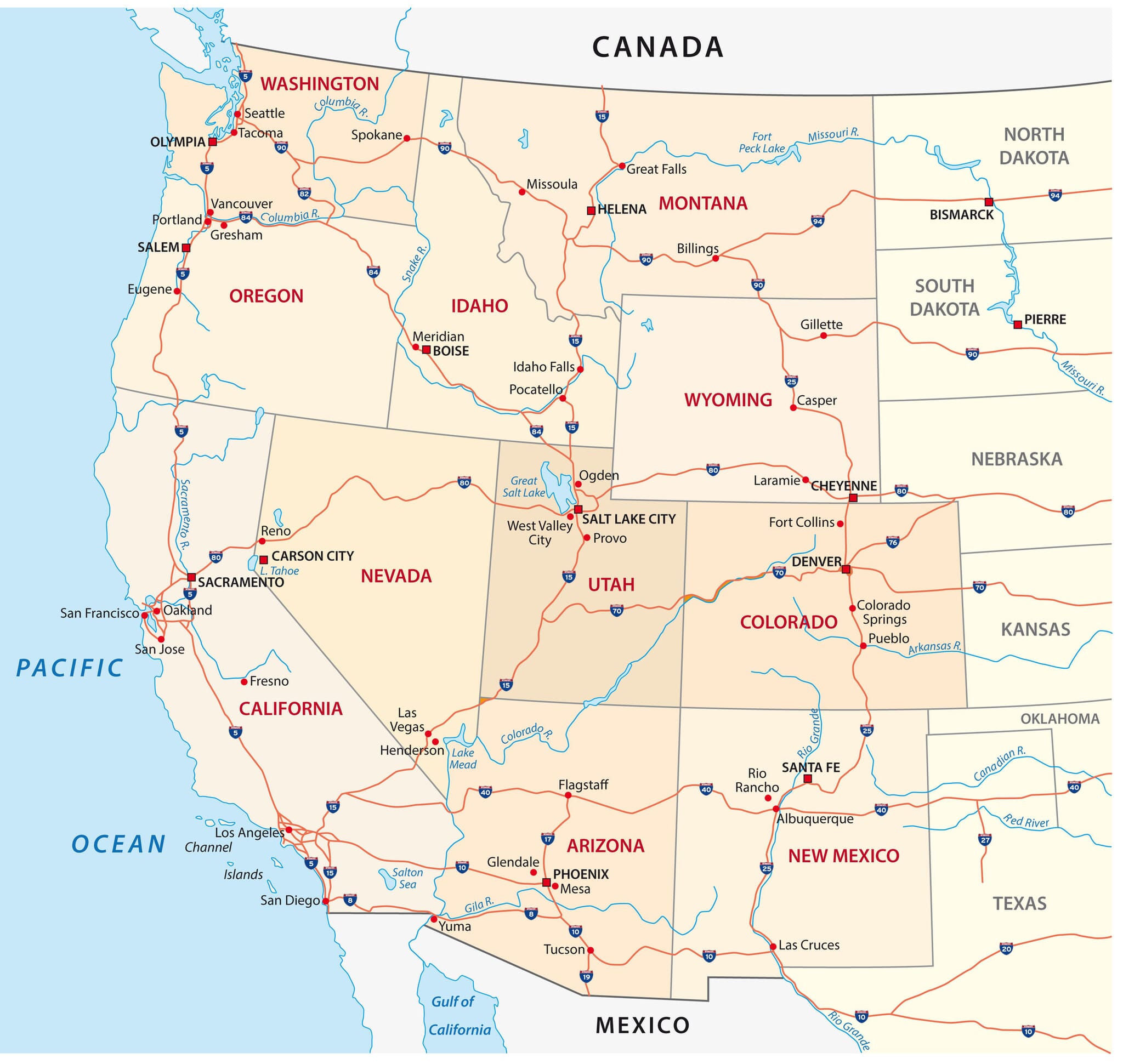

You’re staring at a screen. Or maybe it’s a folded piece of paper that smells like a gas station from 1998. Either way, looking at a map of western united states roads is basically an exercise in humility. You see those long, straight veins of asphalt cutting through Nevada and Wyoming and you think, "I can make it in six hours." You can't. The West doesn't work like the East Coast. Out here, a "road" might be a six-lane interstate or it might be a seasonal path that requires high clearance and a prayer to the gods of tire pressure.

The geography dictates the infrastructure. It’s that simple.

Most people pull up a digital map and see a grid. But the West isn't a grid; it’s a series of obstacles. You’ve got the Rockies acting like a giant, jagged spine. You’ve got the Great Basin, which is essentially a bowl of heat and dust. Then there’s the Pacific Coast Range. When you look at the map of western united states roads, you aren't just looking at transportation routes. You’re looking at a history of where humans were actually allowed to go.

The Great Divide: Why North-South Travel is a Nightmare

Try driving from Boise to Albuquerque. Go ahead. You’ll quickly realize that the American West was built to move people from the Atlantic to the Pacific, not from Mexico to Canada. The major arteries—I-80, I-40, I-10—all run horizontally. These are the descendants of the Oregon Trail and the Santa Fe Trail. They follow the path of least resistance.

If you want to go north or south, you’re often stuck on two-lane highways that wind through canyons. Take US-93. It stretches from the Arizona border all the way up through Montana. It’s beautiful. It’s also exhausting. You’ll be stuck behind a cattle trailer for fifty miles because there’s nowhere to pass and the shoulder is a three-hundred-foot drop.

The Interstate Illusion

Interstates like I-15 and I-5 are the outliers. They’re the only reason you can get from San Diego to Seattle without losing your mind. But even then, nature wins. In the winter, I-80 through Wyoming shuts down more often than a cheap laptop. The wind gets so high it literally blows semi-trucks off the pavement. A map of western united states roads usually fails to show the "Closed" signs that pop up the moment a blizzard hits Elk Mountain.

✨ Don't miss: Alligator River North Carolina: Why This Coastal Swamp Is Weirder Than You Think

The scale is just... wrong. In Pennsylvania, a thirty-minute drive gets you to the next town. In the West, a thirty-minute drive might not even get you past your neighbor’s ranch.

The Loneliest Road and Other Marketing Gimmicks

US-50 in Nevada gets called "The Loneliest Road in America." Life magazine gave it that name in 1986. They meant it as an insult, but Nevada turned it into a badge of honor. Honestly, it’s not even the loneliest road anymore, but it represents the reality of the Western map. It’s a series of "basin and range" transitions. You climb a mountain pass, you drop into a flat desert floor, you drive straight for twenty miles, and you do it again.

Why GPS Lies to You

If you’re relying solely on a digital map of western united states roads, you’re going to get "Death Valley'd." This is a real term used by park rangers. It happens when a GPS tells a tourist to take a "shortcut" through a dirt road in the Mojave or the Great Basin.

- Fact: Digital maps often don't distinguish between paved county roads and "unimproved" Bureau of Land Management (BLM) tracks.

- Reality: That "shortcut" might be a washboard road that shakes the bolts out of your suspension.

- The Consequence: People end up stranded without cell service in 110-degree heat because they thought the blue line on the map was a real road.

Always check the surface type. If the map shows a thin grey line instead of a thick yellow or white one, bring extra water. Better yet, bring a full-sized spare tire, not one of those "donut" things.

The Weird Logic of Western Speed Limits

You’ll notice something funny when you cross into Idaho or Wyoming. The speed limit jumps to 80 mph. This isn't because they’re in a hurry. It’s because the distances are so vast that 65 mph feels like standing still. When the next gas station is 100 miles away, you start to do the math.

But here’s the kicker: the roads aren't always built for those speeds. Frost heaves in Montana can turn a flat highway into a roller coaster. If you’re hitting those at 80, you’re going to catch air.

Seasonal Passes: The Roads That Disappear

One of the most misunderstood parts of any map of western united states roads is the concept of the "seasonal closure." In the East, roads stay open. In the West, the Sierra Nevada and the Cascades just... stop.

The Sierra Nevada Blockade

Take Tioga Pass (Highway 120) in Yosemite. It’s one of the most spectacular drives in the world. It’s also closed for about half the year. If you’re planning a trip in May and your map says it’s the fastest way from Bishop to Manteca, you’re in for a 200-mile detour. The snow there can be thirty feet deep. They don't just plow it; they have to excavate it.

- Tioga Pass (CA): Usually closes November, opens late May or June.

- Beartooth Highway (MT/WY): Known as the most beautiful drive in America. It’s basically a tundra. It closes at the first sign of a flake in September.

- North Cascades Highway (WA): They don't even try to keep it open in winter. The avalanche risk is too high.

If you don't account for these gaps, your "perfect" road trip map is a work of fiction.

The BLM and National Forest Paradox

About 47% of the land in the West is owned by the federal government. This creates a massive network of roads that don't appear on your standard Google Map or Apple Map. These are Forest Service roads and BLM tracks.

These roads are the lifeblood of the West for hunters, campers, and explorers. But they are treacherous. They aren't maintained for your Honda Civic. They’re maintained for logging trucks and fire engines. When you see a map of western united states roads that looks "empty," look closer at a topographical map. It’s actually teeming with thousands of miles of dirt veins.

Safety on the "Invisible" Roads

If you venture onto these, the rules of the road change. Uphill traffic has the right of way. Why? Because it’s harder to get moving again on a steep, gravelly incline than it is to stop while going down. Also, if you see a logging truck, get out of the way. They can't stop, and they won't.

Infrastructure and the "Rural Renaissance"

Is the map changing? Sort of.

There’s a lot of talk about "The New West." People moving to Bozeman, St. George, and Bend. This is putting an insane amount of pressure on roads that were designed for three tractors and a school bus. Take I-15 through Utah. It used to be a breeze. Now, the "Silicon Slopes" area near Lehi is a permanent traffic jam.

📖 Related: Dalat’s Hằng Nga Crazy House: Why Most Travelers Get This Surreal Landmark Wrong

The map of western united states roads is struggling to keep up with the population shift. We aren't building new interstates. We’re just widening the old ones, and it’s not working. The geography won't allow for much more. You can't just "add a lane" to a road that’s carved into a granite cliff in the Colorado Rockies.

How to Actually Read a Western Road Map

To navigate the West like a pro, you have to stop looking at distance and start looking at time and elevation.

- Check the passes: Use sites like Caltans or WSDOT to see if the road even exists today.

- Fuel is a factor: There is a stretch in Nevada on Highway 50 where the sign literally says "No services for 80 miles." They aren't joking. If your tank is at a quarter, you’re in danger.

- Cellular dead zones: Large swaths of the map of western united states roads have zero bars. Not "weak signal." Zero. Download your maps for offline use or buy a paper gazetteer. Honestly, the Benchmark Road & Recreation Atlases are the gold standard for this.

The West is a place that rewards preparation and punishes arrogance. The roads are the only thing keeping the wilderness at bay, and sometimes, the wilderness wins.

Practical Steps for Your Next Western Journey

Stop treating your GPS like a god. It’s an algorithm, and algorithms don't know about mud season in Vermont (well, the Western equivalent, which is "sticky clay" in Utah).

- Download Offline Maps: Do this before you leave the hotel. Once you hit the canyon floor, you're on your own.

- Verify High-Altitude Routes: If your route goes over 7,000 feet, check the weather and road status, even in "spring."

- Carry a Physical Atlas: A Benchmark or DeLorme atlas shows public land boundaries and road surfaces. It’s the difference between a scenic bypass and a tow truck bill.

- Watch the Wind: If you’re driving a high-profile vehicle (RV, van, truck), check the wind advisories for Wyoming and the Columbia River Gorge.

The map of western united states roads is a guide, not a guarantee. Use it to find the start of your adventure, but keep your eyes on the horizon and your hand on the gas gauge. The West is still wild; the roads just make it easier to see how wild it really is.