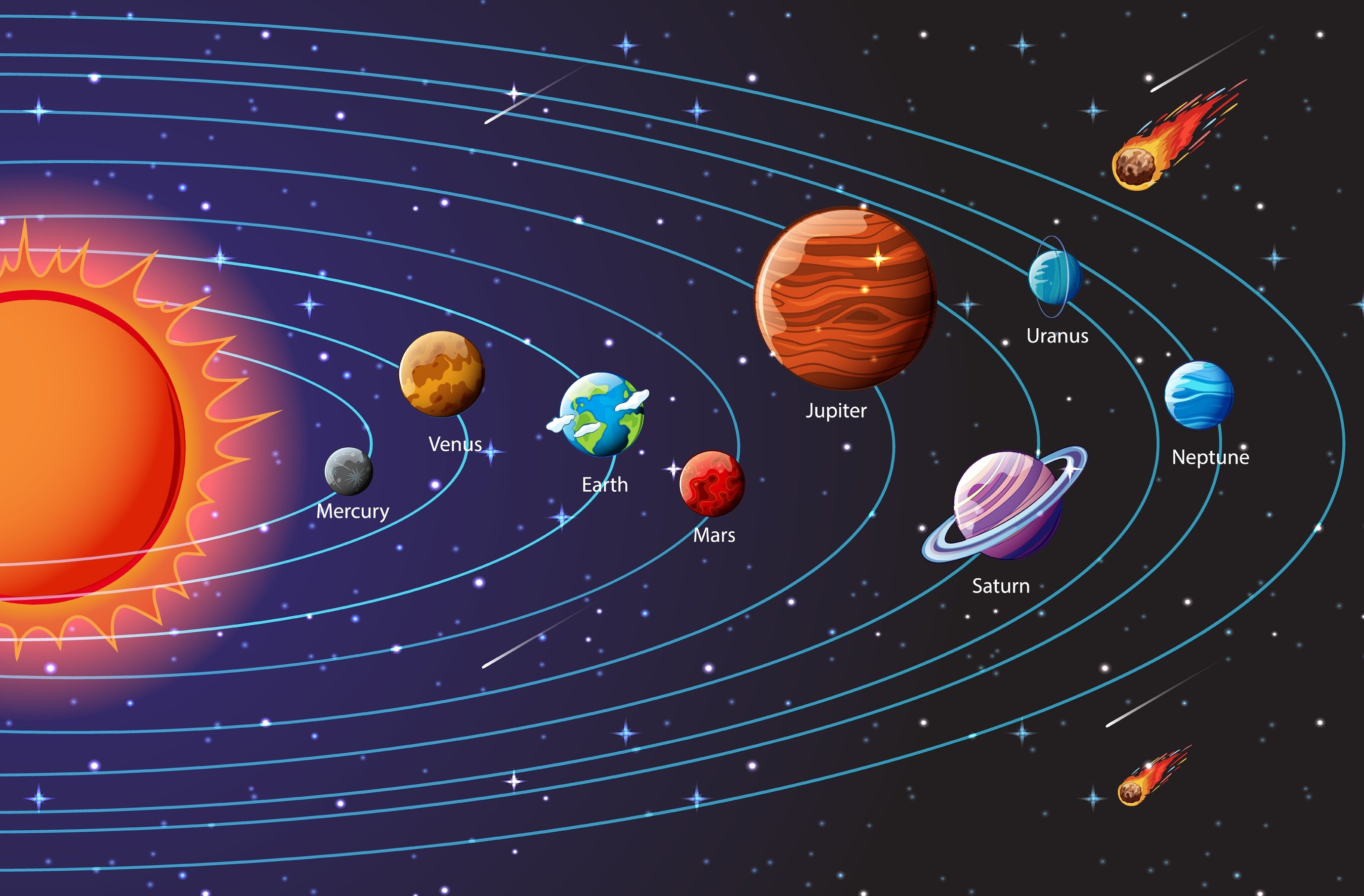

Let’s be real for a second. If you look at a pic of the solar system in a textbook or a quick Google search, you’re looking at a pack of lies. It’s a beautiful, helpful, and totally necessary pack of lies, but it isn’t "real."

Space is big. Like, really big.

If we drew the planets to their actual scale on a single screen, the Earth would be a microscopic speck—smaller than a single pixel—while the Sun would be a massive glowing ball. And the distance between them? You’d be scrolling for miles. Literally. It’s one of those things where our human brains just sort of short-circuit because we aren’t built to understand that much nothingness.

The Scale Problem: Why Your Favorite Pic of the Solar System Is Wrong

The most common pic of the solar system you'll see shows the planets lined up like a bunch of marbles on a table. They look close together. They look roughly the same size. But in reality, the solar system is mostly just empty space.

Astronomers like Mike Brown at Caltech or the folks at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) have to deal with this "scale gap" every day. If you want to see the planets and the orbits at the same time, you have to cheat. You have to make the planets thousands of times larger than they actually are, or the viewer wouldn't see anything but the Sun.

Take the "Pale Blue Dot" photo. Captured by Voyager 1 in 1990 at the request of Carl Sagan, it’s perhaps the most honest pic of the solar system ever taken. Earth is less than a pixel wide. It’s a tiny, fragile speck of dust suspended in a sunbeam. That’s the reality. It’s lonely. It’s dark. Most digital renderings skip that because, honestly, a black screen with three tiny dots doesn’t sell many posters.

Color is Kinda Subjective Out There

When you see a vibrant, neon-blue photo of Neptune or a swirling, crimson Jupiter, you're seeing "enhanced" data. Most space cameras, like those on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) or the older Hubble, don't actually take "color" photos the way your iPhone does.

They take data.

They capture light in specific wavelengths—sometimes wavelengths humans can't even see, like infrared. Scientists then assign colors to these wavelengths to help us distinguish between different gases or temperatures. So, that pic of the solar system showing a bright green cloud on a moon? That might actually represent methane levels rather than what you'd see if you were standing there in a spacesuit.

The Methane Mystery on Uranus and Neptune

For decades, we thought Neptune was a deep, royal blue and Uranus was a pale cyan. Why? Because the images from the Voyager 2 flybys in the 80s were processed to emphasize atmospheric features. It wasn't until a 2024 study led by Professor Patrick Irwin at the University of Oxford that we got a more accurate look. By re-processing the original data with modern calibration, we found out both planets are actually a similar shade of pale, greenish-blue.

Neptune is just slightly bluer because its haze layer is a bit thinner. We’ve been looking at "wrong" versions of these planets for forty years because the "pretty" version became the standard.

The "Orrery" Style vs. Reality

Most people think the planets orbit the sun in a flat, perfect circle. We call these "orrery" views. While the planets do mostly sit on a flat plane called the ecliptic, their orbits are elliptical—sort of egg-shaped.

And they are constantly moving.

A static pic of the solar system implies a moment frozen in time, but the Sun itself is hauling through the galaxy at about 448,000 miles per hour. The planets are chasing it, spiraling through the Milky Way in a massive, cosmic vortex. If you ever see a 3D animation of the "Solar Vortex," it’s a bit controversial among physicists because of the way it's framed, but it captures the vibe of constant motion much better than a flat map ever could.

✨ Don't miss: Why Half of 32 Is the Foundation of Digital Logic

Where Do the Images Actually Come From?

We don't have a camera sitting "above" the solar system looking down. We can't. To get a true "top-down" pic of the solar system, we’d have to send a probe incredibly far out of the plane of the planets, which takes an enormous amount of fuel and time.

Most of what we have are mosaics.

- Mariner 10: Gave us the first real look at Mercury’s cratered surface.

- Viking 1 and 2: Showed us the red dust of Mars wasn't just a guess.

- Cassini-Huygens: Spent 13 years at Saturn, giving us those mind-bending shots of the rings that look like they're made of glass.

- New Horizons: That famous "heart" on Pluto? That was 2015. Before that, Pluto was just a blurry blob of pixels.

When NASA "releases" a new pic of the solar system, it's usually a composite of hundreds of smaller images stitched together. It’s like a giant jigsaw puzzle where the pieces were taken hours or even days apart.

The Asteroid Belt Isn't a Minefield

Thanks to Star Wars, everyone thinks the Asteroid Belt is a crowded mess where you’re constantly dodging space rocks. It’s not. If you stood on an asteroid in the belt, you probably wouldn't even see another asteroid with the naked eye. They are millions of miles apart.

When you see an infographic or a pic of the solar system that shows a dense ring of rocks between Mars and Jupiter, it’s just to show you where they live, not how they actually look. If we drew them to scale, the belt would be invisible.

How to Find a "Real" Image

If you want to see what things actually look like without the Hollywood glow-up, you have to look for "True Color" or "Natural Color" labels.

- Check the Raw Data: Websites like the Planetary Data System (PDS) host the raw, unprocessed files from missions. They are usually black and white and look pretty grainy.

- Look for Artist Impressions: If a pic of the solar system shows a planet from a surface we haven't landed on (like the clouds of Venus), it’s an artist’s impression. These are based on radar data, but the "lighting" is a creative guess.

- The "Blue Marble" Legacy: The most famous "real" photo is the 1972 Blue Marble shot. It was taken by the crew of Apollo 17. No filters, no stitching, just a Hasselblad camera and a lot of sunlight.

Why the "Fake" Pictures Still Matter

Even if a pic of the solar system is stylized, it serves a purpose. We use false color to see where water ice is hiding on the Moon. We use exaggerated scales to understand the tilt of Uranus (which rolls on its side like a bowling ball).

Without these visual aids, space would be too abstract to care about. We need the "lies" to understand the truth.

Practical Ways to Explore the Solar System Digitally

If you're tired of static images and want to see the real layout, stop looking at JPEGs and start using simulators.

- NASA’s Eyes on the Solar System: This is a free web-based tool that uses real trajectory data. You can "ride along" with the Juno spacecraft at Jupiter or see exactly where the Perseverance rover is on Mars right now. It uses real 3D models and shows the actual distance between objects.

- Stellarium: This is great for seeing how the solar system looks from your backyard. It’s open-source and shows you exactly which "star" in the sky is actually Saturn or Venus.

- If the Moon Were Only 1 Pixel: This is a famous website by Josh Worth. It’s a tedious, mind-numbing, and absolutely brilliant scroll-based map of the solar system. It’s the only way to truly "feel" how much empty space there is.

Instead of just looking at a flat pic of the solar system, use these tools to gain a sense of depth. Search for "JPL Raw Images" to see the latest, unedited transmissions from Mars or the outer planets. Understanding that space is mostly "nothing" actually makes the "something"—the planets, the moons, and us—feel a whole lot more significant.