Ever walked past a newspaper—if those still exist in your world—and saw a drawing of a guy trying to sell lemonade for fifty bucks while a crowd walks away? That’s the classic supply and demand cartoon. It’s basically the "Hello World" of economic education.

Economics is dry. Honestly, it’s like chewing on cardboard sometimes. Graphs with their intersecting $X$ and $Y$ lines make people’s eyes glaze over faster than a boring lecture on tax law. But a cartoon? That sticks. It’s why teachers, Twitter pundits, and even the The New Yorker keep leaning on them. They take the invisible hand of Adam Smith and give it a funny hat.

The Visual Language of Scarcity

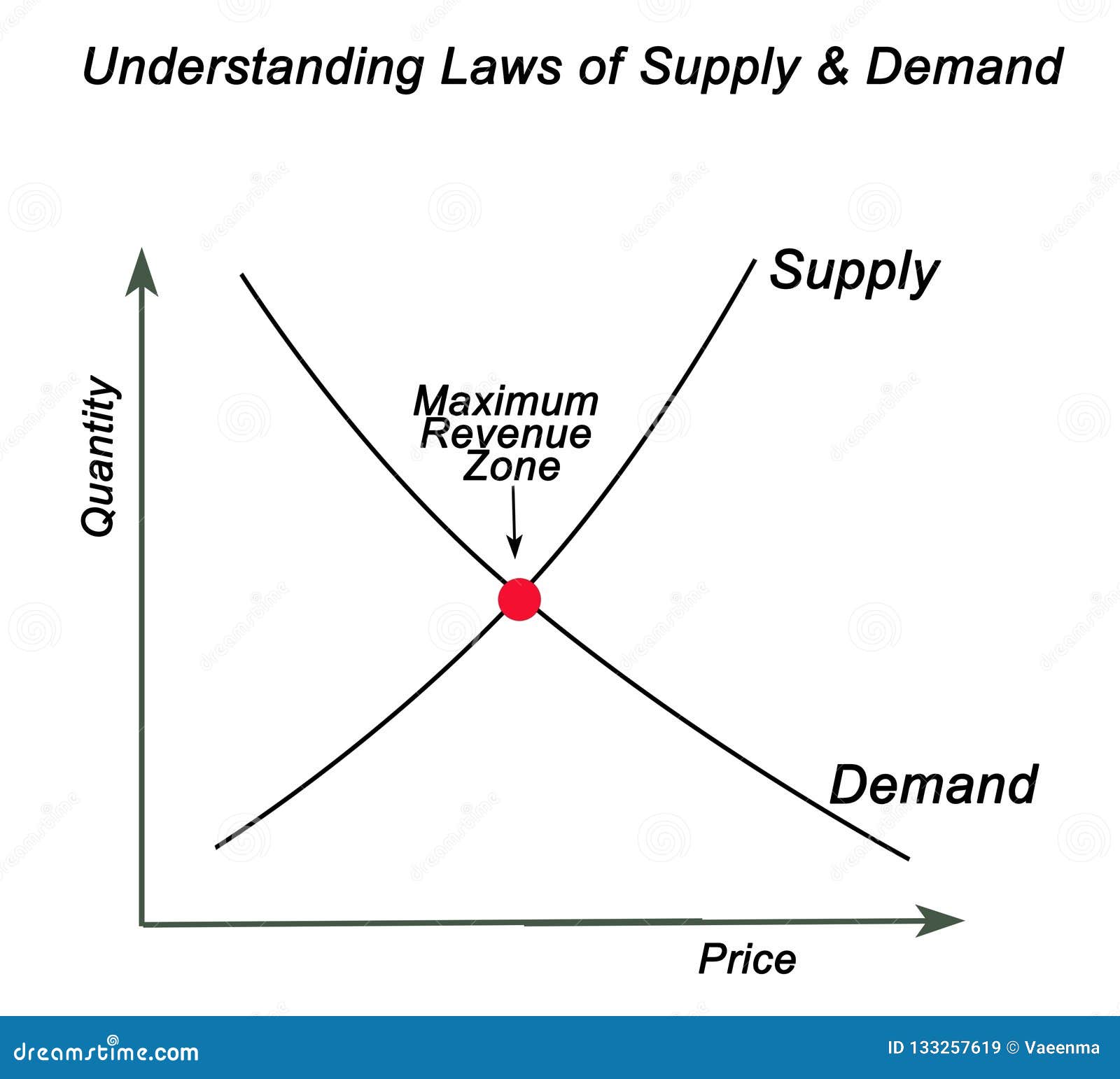

Most people think these cartoons are just jokes. They aren't. They’re functional models. When you see a supply and demand cartoon featuring a line of people a mile long for a single loaf of bread, your brain instantly computes "high demand, low supply." You don't need a PhD to get it.

You've probably seen the one by Peter Steiner or maybe a classic Wall Street Journal bit where a CEO is staring at a plummeting line on a chart. The humor usually comes from the lag—the moment where the characters realize they’ve messed up the pricing. If the price is too high, the character is lonely. If it’s too low, they’re being trampled. It’s simple.

Maybe too simple?

The problem with a supply and demand cartoon is that it often ignores "elasticity." That’s a fancy word economists like Alfred Marshall used to describe how sensitive people are to price changes. If a cartoon shows someone selling air, they can charge whatever they want because you’ll die without it. That’s perfectly inelastic. If they’re selling a specific brand of purple shoelaces? People will just walk away. Most cartoons miss that nuance. They treat everything like it's a life-or-death struggle for a single resource.

Why the "Invisible Hand" Needs a Punchline

Let's talk about the 1970s. Inflation was rampant. Oil prices were a nightmare. This was the golden age for the supply and demand cartoon. Editorial cartoonists like Jeff MacNelly or Herblock had a field day. They’d draw the American consumer as a tiny person being crushed by a giant barrel of oil labeled "Supply."

It works because it personifies forces that feel totally out of our control.

Think about the toilet paper shortage of 2020. Remember that? The internet was flooded with cartoons of people trading gold bars for a single roll of Charmin. That is a supply and demand cartoon in its purest, most frantic form. It captured the "Panic Buying" phenomenon better than any 40-page white paper from Brookings ever could.

Breaking Down the Classic Tropes

- The Lemonade Stand: This is the base level. Usually involves a kid learning that nobody wants 5-cent lemonade when it’s raining.

- The Desert Island: Two guys, one bottle of water, and a bag of diamonds. It’s the ultimate lesson in "utility." Diamonds are useless if you’re dying of thirst. Supply is one. Demand is infinite.

- The Empty Shelf: A commentary on price caps. When the government says "You can't charge more than $X$," the supply vanishes. Cartoons love showing the "Black Market" guy standing in the alleyway as a result.

The supply and demand cartoon often serves as a political weapon. If you're a free-market fan, you draw the government as a heavy weight sitting on the supply curve. If you’re more of a regulation person, you draw the "Supply" side as a greedy monster hoarding all the toys.

The Psychology Behind the Sketch

Why do we remember these?

It’s the "Superiority Theory" of humor. We see the guy in the cartoon making a stupid mistake—like trying to sell snow to Alaskans—and we feel smart because we understand the market better than he does. It’s a shortcut to expertise.

But there’s a trap here.

Reliance on a supply and demand cartoon can make us think economics is always a 1:1 ratio. It’s not. In the real world, we have "Veblen goods." These are things like Rolexes or Birkin bags. Usually, when the price goes up, demand goes down, right? Not with these. When the price goes up, demand actually increases because people want the status. You rarely see a cartoon explaining that because it’s hard to draw "conspicuous consumption" without it just looking like someone being a jerk.

Famous Examples You’ve Definitely Seen

You cannot talk about this without mentioning The New Yorker. They have a specific vibe. Usually, it’s two guys in suits. One says something like, "We’ve decided to increase the price of the 'Free' plan to 'Extremely Expensive' due to a sudden increase in my desire for a boat."

✨ Don't miss: Finding 60 percent of 700: Why This Specific Math Matters for Your Wallet

That’s a supply and demand cartoon that critiques the "Supply" side’s ego.

Then you have the more technical ones found in textbooks like those by Greg Mankiw. These aren't really "funny," but they use cartoonish characters to soften the blow of learning about deadweight loss. They use a mascot to point at the equilibrium point. It’s a bit condescending, but hey, it helps freshmen pass Macro 101.

Beyond the Paper: Digital Evolution

Now, we have memes. A meme is just a supply and demand cartoon that’s gone through a blender.

Think of the "Stonks" meme. It’s a surrealist take on market forces. It mocks the idea that we actually understand why prices move. Sometimes demand goes up because a guy on Reddit said so. Sometimes supply drops because a ship got stuck in the Suez Canal.

The supply and demand cartoon of 2026 is often a multi-panel comic on Instagram or a quick TikTok animation. It’s faster. It’s meaner. It usually involves a lot more cynicism about "Late Stage Capitalism."

Accuracy Check: Does the Math Hold Up?

If you look at a supply and demand cartoon through the lens of a real economist like Thomas Sowell or Paul Krugman, you’ll find holes.

- Information Asymmetry: Most cartoons assume everyone knows the price and the quality. In reality, the seller usually knows way more than the buyer.

- Irrationality: Cartoons assume we are "Homo Economicus"—perfectly rational beings. Real humans are messy. We buy things because we’re sad, or bored, or because our neighbor has one.

- Externalities: A cartoon about a factory producing "Supply" rarely shows the smoke killing the trees in the background.

Despite these flaws, the supply and demand cartoon remains the most effective "gateway drug" to understanding how the world trades. It distills the chaos of 8 billion people wanting things into a single, relatable moment of frustration or realization.

To really get the most out of these visual lessons, you have to look for what isn't in the frame. Who is the person not buying? Why is the shelf empty? Is it because the price is too low, or because the truck broke down?

Actionable Insights for Using Visual Economics

- Audit Your Messaging: If you're a business owner, think of your pricing page as a supply and demand cartoon. Is it clear why your price is what it is? If customers are confused, you have a "bad caption" problem.

- Identify the "Scarcity" Hook: Use the logic of these cartoons to find your unique value. If everyone is selling the same thing (high supply), your "Demand" will only spike if you change the "Utility" (the reason they want it).

- Question Simple Narratives: Next time you see a political cartoon about the economy, ask: "Which curve are they hiding?" Usually, they focus on supply and ignore demand, or vice versa, to make a point.

- Teach with Visuals: If you have to explain a complex topic to a team, don't use a spreadsheet first. Use a sketch. Even a crude drawing of a "Supply and Demand" scenario can align a team faster than a 20-slide deck.

The world is just one giant, messy, high-stakes cartoon. Understanding the basic lines of the sketch makes it a lot easier to figure out where you fit into the picture. No matter how complex the algorithms get, it still usually comes down to a guy with a thing and a guy who wants the thing. That's the heart of it.

Stop looking for the perfect graph and start looking for the story the market is telling. Usually, there’s a punchline if you look close enough.