Most people treat their hips like a simple hinge. They squat, they lung, and they walk, thinking they’ve covered all the bases because their legs are moving. But the hip isn’t a hinge; it’s a ball-and-socket joint designed for 360 degrees of chaos. When you neglect the smaller stabilizers, things start to break. You feel it in your lower back during a long walk, or maybe it's that nagging ache on the outside of your knee that just won't quit. This is exactly where the four way hip exercise comes into play. It’s not flashy, and you won’t see many influencers doing it with 400 pounds on their back, but it is the literal foundation of athletic longevity.

If you’ve ever spent time in a physical therapy clinic, you know the drill. You’re likely standing at a cable machine or hooked into a set of resistance bands, moving your leg in four distinct directions. It feels easy at first. Then, about twelve reps in, your glutes start screaming in a way that’s totally different from a heavy deadlift. That’s because you’re finally hitting the gluteus medius, the minimus, and the psoas—the "forgotten" muscles that actually keep your pelvis level when you move.

What the four way hip exercise actually fixes

We live in a world that moves forward and backward. We run in straight lines. We sit in chairs. This creates a massive imbalance. Your "prime movers"—the quads and hamstrings—get all the work, while the lateral stabilizers turn into mush. When those stabilizers fail, your femur starts to rotate inward when you walk or run. Doctors call this "valgus collapse," but you probably just call it "my knee hurts."

By performing the four way hip exercise, you’re forcing the hip to stabilize against resistance in flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction.

Flexion hits the hip flickers, primarily the psoas. Extension targets the glute max and hamstrings. Abduction (moving away from the midline) is the holy grail for knee health because it strengthens the gluteus medius. Adduction (moving toward the midline) works the inner thighs, which are crucial for pelvic floor health and groin strain prevention. Honestly, if you aren't doing these, you're leaving a massive gap in your armor.

💡 You might also like: Pat of Butter Calories: What Your Server Actually Put on Your Plate

The four movements explained (without the fluff)

Let’s break down what’s actually happening in each phase.

First is Hip Flexion. You’re standing tall, and you kick your leg straight forward. Most people cheat here by leaning back. Don't do that. You’re trying to isolate the hip flexors. If you feel your lower back arching, you’ve already lost the rep. The goal is a steady, controlled lift that stops right before your pelvis starts to tilt.

Then comes Hip Extension. This is the kickback. You move your leg behind you. It’s tempting to lean forward and turn this into a bird-dog variation, but stay upright. You should feel a deep squeeze in the lower glute. It’s a small movement. If your leg is swinging three feet behind you, you’re likely using momentum or your lumbar spine to get there.

Third is Hip Abduction. This is the one everyone hates because it reveals how weak we really are. You kick your leg out to the side. Keep your toes pointed straight ahead or even slightly turned inward. If your toes point toward the ceiling, you’re using your hip flexors instead of your lateral glutes. This is the movement that stops your knees from caving in when you squat.

Finally, there’s Hip Adduction. You cross your working leg in front of your standing leg. It feels awkward. It looks a bit like a soccer kick. But it strengthens the adductor group, which acts as a secondary stabilizer for the entire leg.

Why physical therapists are obsessed with this

Stuart McGill, the world-renowned spine biomechanics expert, often talks about the "hip-spine connection." If your hips don't move, your spine will. It has to. The four way hip exercise is a staple in the "McGill Big 3" philosophy adjacent rehab because it builds "proximal stiffness."

When the muscles surrounding the hip are strong, they act like guy-wires on a ship’s mast. They hold the pelvis steady. Without that steadiness, your lower back (the lumbar spine) has to do the stabilizing work it wasn't designed for. That's how you end up with "mystery" back pain that won't go away with stretching. You don't need a more flexible back; you need more stable hips.

🔗 Read more: Facing the Reality of a Grandma in Hospital Bed: What No One Tells You About the Wait

Common mistakes that kill your progress

People mess this up constantly. The biggest culprit? Using too much weight.

This isn't a power exercise. If you load up the cable machine and start huffing and puffing, your body will find a way to use "cheat" muscles to move the load. Your torso will sway like a willow tree in the wind. To do the four way hip exercise correctly, your upper body should be a statue. Only the leg moves. If you find yourself holding onto the machine for dear life just to stay upright, drop the weight.

Another big one is "pelvic hiking." This happens during abduction. Instead of using the hip muscles to lift the leg, people use their oblique muscles to "hike" their hip upward toward their ribs. It looks like you're doing the exercise, but your glutes are essentially on vacation.

Resistance bands vs. Cable machines

You've got options here. Cable machines provide constant tension, which is great for muscle hypertrophy. However, resistance bands—specifically the "mini-band" style—are often better for developing the "feel" of the exercise.

Bands have a variable resistance curve. The further you stretch them, the harder they get. This teaches your brain how to "end-range" the movement. If you're traveling or working out at home, a $10 set of bands is all you need to get a world-class hip workout. Honestly, sometimes the bands are actually harder because they force a faster eccentric (the way back) which you have to fight to control.

The surprising link to athletic speed

Sprinting is basically a series of violent hip flexions and extensions. If your hip flexors are weak, you can't drive your knee up fast enough. If your glutes are weak, you can't push off the ground with enough force.

But it's the lateral work—the abduction and adduction—that keeps you from "leaking" power. Imagine trying to jump off a trampoline made of Jell-O. That’s what it’s like to try and sprint with weak lateral hip stabilizers. Your energy dissipates sideways instead of driving you forward. Integrating the four way hip exercise into a track or field athlete's routine often results in immediate, measurable improvements in agility and "cutting" speed because the pelvis stays stable during directional changes.

Setting up your routine

Don't overthink it. You don't need a "Hip Day."

Instead, use the four way hip exercise as a warm-up. Do two sets of 15 reps in each direction before you squat or run. It "wakes up" the nervous system and tells your glutes it’s time to work.

👉 See also: Condoms in Use for Kids: A Practical Guide to the Hardest Conversations

- Flexion: 2 sets of 12-15 reps (Focus on upright posture)

- Extension: 2 sets of 12-15 reps (Squeeze the glute, don't arch the back)

- Abduction: 2 sets of 15-20 reps (Toes forward, no hiking)

- Adduction: 2 sets of 12-15 reps (Slow and controlled)

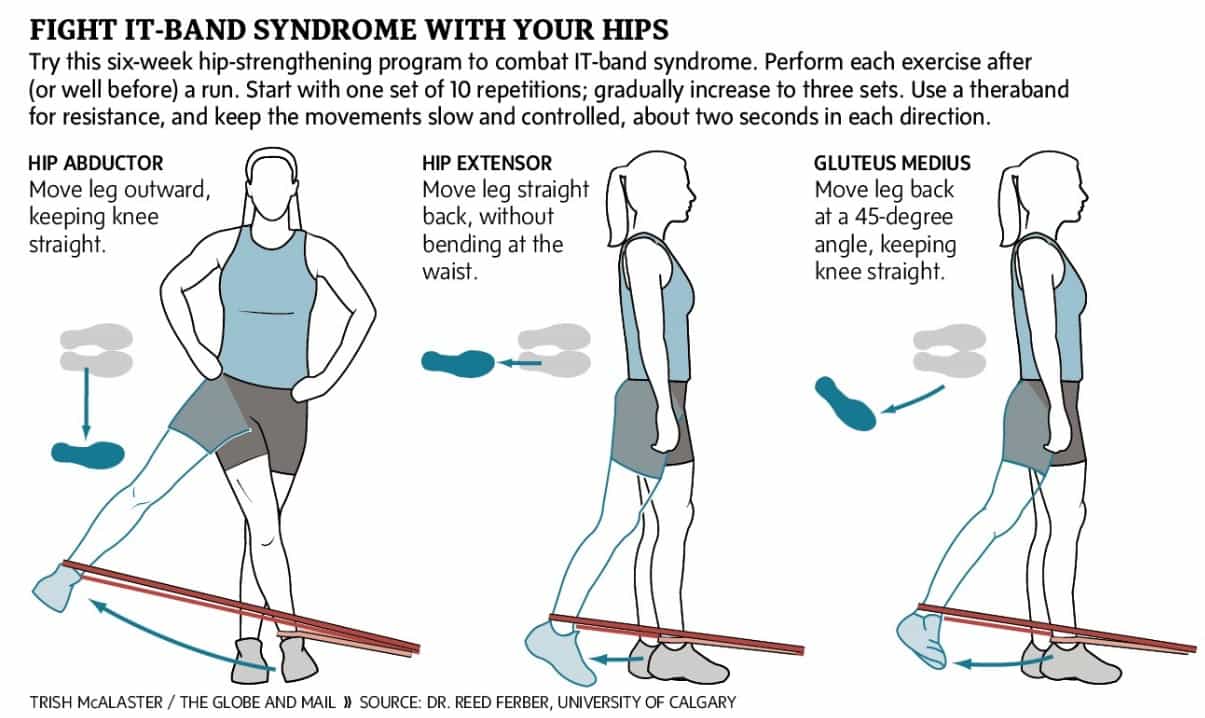

If you're dealing with an active injury, like IT band syndrome or runner's knee, you might want to bump the frequency to every other day. Just remember that these are small muscles. They fatigue quickly. Pushing through "bad" reps where your form breaks down is counterproductive.

The "So What?" of hip health

It’s easy to ignore the small stuff. We want big numbers and visible results. But the four way hip exercise is the "maintenance work" that allows the big numbers to happen. It's the difference between being a "lifter" for three years before your joints give out and being someone who stays active into their 70s.

It's sorta like changing the oil in your car. It's boring. It's a chore. But if you don't do it, the whole engine eventually seizes up. Your hips are the engine of your movement. Treat them that way.

Start by adding the abduction (side-kick) movement to your next workout. Just that one. Notice how your balance feels afterward. Notice how your knees feel during your next set of lunges. Usually, the feedback is almost instant. Once you feel that stability, you won't want to go back to training without it.

Actionable Next Steps

- Test your baseline: Stand on one leg for 30 seconds. If your hip drops or you wobble significantly, your lateral stabilizers are weak.

- Pick your tool: Buy a set of looped resistance bands or locate the "multi-hip" machine at your gym.

- Implement the "Light and Right" rule: Start with the lightest resistance possible. Perform 15 reps of the four way hip exercise in all four directions. If you can't keep your torso perfectly still, the resistance is too high.

- Frequency over intensity: Do this 3 times a week for 14 days. Most users report a significant reduction in "nagging" knee and lower back tightness within the first two weeks of consistent activation.