Gustav Mahler Symphony No. 2 is a lot to take in. Honestly, calling it a "symphony" feels like an understatement, because it’s more like an hour-and-a-half-long existential crisis that ends in total euphoria. If you’ve ever sat in a darkened concert hall and felt the floor vibrate under the weight of ten horn players and a massive choir screaming about eternal life, you know exactly what I’m talking about. It’s loud. It’s quiet. It’s terrifying.

Most people call it the "Resurrection" Symphony. That’s a heavy title, but Mahler wasn't exactly known for keeping things light and breezy. He spent years—six, to be exact—fiddling with this thing, trying to answer the biggest question humans have ever asked: Does life actually mean anything, or is it just a cruel joke before we die?

He started it in 1888, and he didn't finish until 1894. That’s a long time to spend thinking about death. But the result is arguably the most powerful piece of music ever written for a stage.

The Weird Struggle of Writing the "Resurrection"

Writing a follow-up to his First Symphony was a nightmare for Mahler. He had the first movement done pretty quickly—a funeral march that he originally called Totenfeier (Funeral Rites). But then he got stuck. Like, really stuck. He knew he wanted a big finish with a choir, but he was terrified of being compared to Beethoven’s Ninth.

Imagine trying to write a pop song and worrying it sounds too much like "Bohemian Rhapsody." That was Mahler’s life.

The breakthrough finally happened in 1894 at a funeral for the conductor Hans von Bülow. During the service, the choir sang a hymn by Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock called Die Auferstehung (The Resurrection). Mahler later said it hit him like a lightning bolt. He rushed home and started writing. He used some of Klopstock’s words but added his own because he wanted to make sure the message wasn't just "churchy" but deeply personal.

Breaking Down the Five Movements (Without the Academic Fluff)

You don't need a music degree to get why this piece works. It’s structured like a journey.

Movement One is the funeral. It’s aggressive. It starts with this low, growling tremolo in the strings that feels like something is stalking you. Mahler actually instructed that there should be a five-minute break after this movement because it’s so draining. Most modern conductors don't wait that long because the audience gets fidgety, but the intent was clear: sit there and think about what you just lost.

💡 You might also like: Camp Flog Gnaw 2025: Why Tyler, The Creator Still Has the Best Festival in Rap

Movement Two and Three are weirdly nostalgic. The second movement is a Ländler—basically an Austrian folk dance. It’s like a happy memory of a life that's already over. Then the third movement kicks in, and things get cynical. It’s based on a song Mahler wrote about St. Anthony preaching to the fish. The fish listen, they’re impressed, and then they go right back to eating each other. It’s a bitter musical joke about how people never change.

Then comes Urlicht.

This is the fourth movement, and it’s just a lone mezzo-soprano singing about a "Primal Light." After all the noise and cynicism of the first three parts, this is the moment where the soul basically says, "I'm tired, and I'm going back to God." It’s incredibly fragile. If the singer is good, there usually isn't a dry eye in the house.

That Massive Finale

The fifth movement is where the "Gustav Mahler Symphony No. 2" earns its reputation. It’s nearly thirty minutes long. It starts with a "cry of despair"—a literal wall of sound that feels like the end of the world. Mahler uses offstage brass to create a sense of space, like you’re hearing trumpets calling from the other side of the valley.

Eventually, the choir enters. They don't blast it out at first; they whisper. They sing about rising again, and the music builds and builds until every single person on stage is going at full tilt. Organs, bells, two soloists, a full choir, and a massive orchestra. It’s designed to be overwhelming. It’s not just a "nice" ending; it’s a sonic assault that’s supposed to make you feel like you’ve actually conquered death.

Why Does This Matter Today?

We live in a world of three-minute TikTok sounds and AI-generated background music. In that context, Gustav Mahler Symphony No. 2 is an anomaly. It demands your attention for eighty minutes. It’s the opposite of "low-fi beats to study to."

Leonard Bernstein, who basically became the face of Mahler in the 20th century, argued that Mahler was the "prophet" of our age because his music contains everything—the ugly, the beautiful, the banal, and the divine. He didn't filter anything out.

There’s a common misconception that Mahler’s music is "depressing." Sure, he talks about death. A lot. But the Second Symphony isn't about staying dead. It’s about the refusal to be defeated by the randomness of life. That’s why people still flock to see it. We’re all kind of looking for that same reassurance.

Technical Insanity: What it Takes to Perform

If you’re a concert promoter, scheduling this symphony is a logistical nightmare. You need:

- At least 10 horns (four of them offstage).

- A massive percussion section including "deep bells" and a Rute (a bundle of sticks).

- A pipe organ (electronic versions rarely cut it).

- Two high-level soloists (Soprano and Mezzo-Soprano).

- A choir large enough to be heard over a hundred instruments.

Because of this, it’s expensive to produce. It’s an event. When a local orchestra announces they’re doing Mahler 2, it’s a big deal.

Getting the Most Out of Your First Listen

If you're new to this, don't just put it on in the background while you’re doing dishes. You’ll miss the nuances, and the loud parts will probably just annoy you.

- Find a good recording. Gilbert Kaplan is a fascinating case study here—he wasn't a professional conductor, just a wealthy businessman who became obsessed with this one symphony and spent his life learning how to conduct it. His recording with the Vienna Philharmonic is surprisingly precise. For something more visceral, look for Bernstein or Simon Rattle.

- Read the lyrics. The text of the final movement is everything. When the choir sings "Believe, my heart, nothing is lost to you," it hits differently when you know the words.

- Watch a live performance video. Seeing the physical effort the musicians put in adds a layer of drama you can't get from audio alone. You can see the sweat. You can see the percussionists switching between five different instruments.

The Verdict on Mahler’s Legacy

Gustav Mahler Symphony No. 2 isn't just a piece of music; it's an endurance test for the soul. It forces you to sit with discomfort before giving you the payoff. In a culture that prioritizes instant gratification, Mahler makes you work for your catharsis.

📖 Related: Why the Cast of Personal Taste Still Rules the K-Drama World 15 Years Later

It’s messy. It’s sometimes a bit over-the-top. But that’s exactly why it feels human. Mahler didn't want to write a "perfect" piece of music; he wanted to write a piece of music that contained the whole world. And honestly? He pretty much nailed it.

Actionable Next Steps for the Curious Listener

If you want to actually understand why this piece is a masterpiece, don't just take my word for it.

- Listen to the "Urlicht" movement first. It’s only five minutes long and acts as a perfect gateway drug to the rest of the symphony.

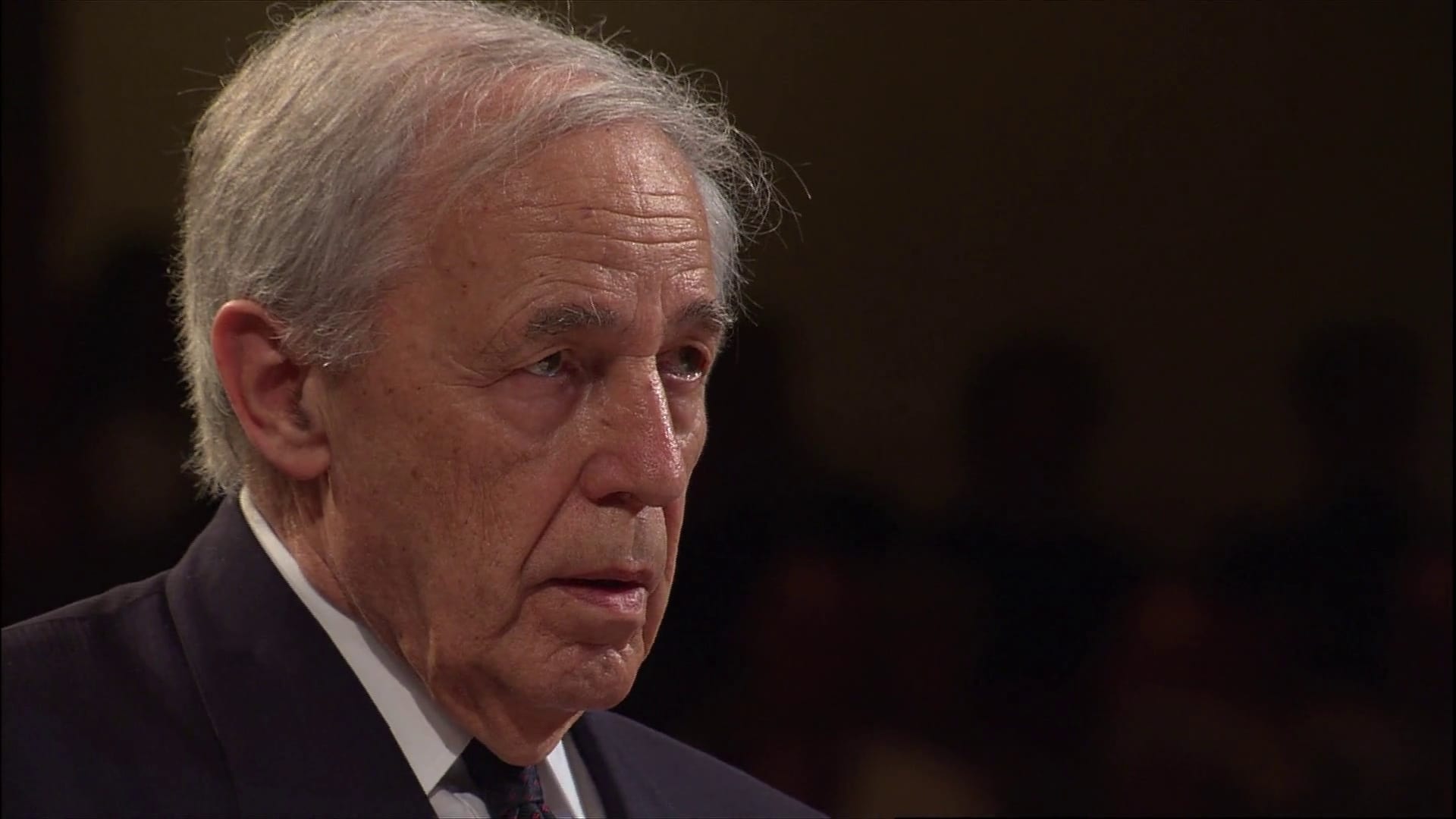

- Compare two conductors. Listen to the finale conducted by Leonard Bernstein (very emotional, lots of rubato) and then listen to Pierre Boulez (very clean, intellectual). You’ll realize how much a conductor actually shapes the "meaning" of the notes.

- Check your local symphony’s calendar. This is a piece that must be experienced live at least once. The physical vibration of the low brass in the room is something no pair of headphones can replicate.

Go find a quiet hour, turn off your phone, and let the "Resurrection" do its thing. You might come out the other side feeling a little bit different about the world.