Ever looked at a 1967 Mustang and thought, "I could never sketch those lines"? You aren't alone. Most people fail because they try to draw a car. That sounds stupid, right? But stay with me. If you set out to draw a "car," your brain defaults to a generic symbol—a box on wheels. To actually master how to draw a classic car, you have to stop seeing the vehicle and start seeing the physics of light hitting metal. It’s kinda like magic, but with more graphite and fewer rabbits.

Classic cars are different from modern SUVs. Modern cars are shaped by wind tunnels and pedestrian safety laws, which makes them look like melted bars of soap. Classics? They were shaped by stylists like Harley Earl and Bill Mitchell. They have hips. They have "coke-bottle" styling. They have chrome that reflects the entire world around them. If you get the perspective wrong by even a fraction of an inch, the whole thing looks like a crushed soda can.

The Secret Perspective of the 1950s and 60s

The biggest mistake beginners make is starting with the headlights. Don't do that. Honestly, it's the fastest way to ruin a piece of paper. You need to build a crate first. Think of the car as being trapped inside a transparent glass box. If you can't draw a box in two-point perspective, you’ll never get a 1957 Chevy Bel Air to look right.

Scott Robertson, a legendary concept artist and author of How to Draw, always emphasizes the "ground plane." You have to establish where the wheels touch the dirt before you even think about the grill. Draw a long rectangle in perspective. This is your footprint. Most classic American cars follow a specific ratio. The wheelbase—the distance between the centers of the wheels—is usually about three to four "wheel-widths" long. If you're sketching a European classic like a Jaguar E-Type, those proportions shift because the hood (or bonnet, if you're feeling fancy) is obscenely long compared to the cabin.

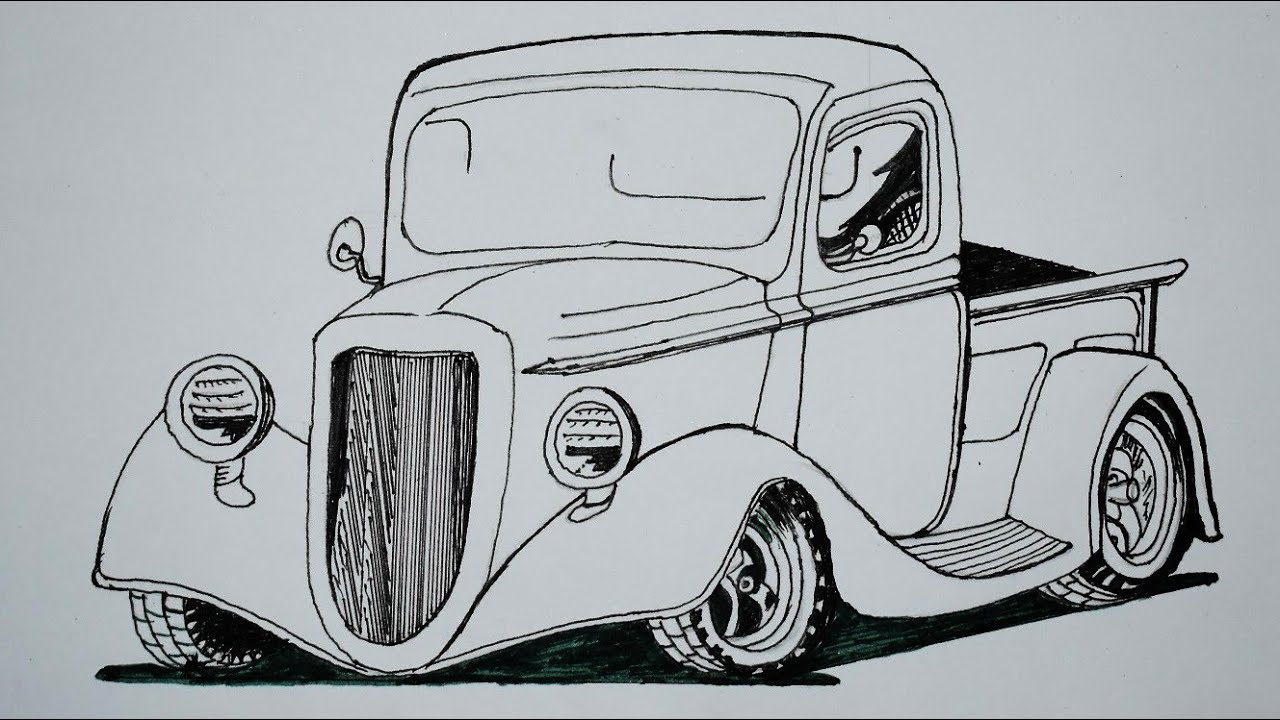

Wheel Ellipses are the Devil

Let's talk about wheels. They aren't circles. Unless you are looking at the car dead-on from the side, those wheels are ellipses. And not just any ellipses. They have a "minor axis" that must point toward the vanishing point of the car’s axle. If your ellipses are tilted the wrong way, the car looks like its wheels are falling off. It’s a common trope in bad fan art. You've seen it. The car looks great, but it feels like it’s sliding off the page. That's a minor axis issue.

Mapping the "Bone Structure" of Your Classic Car

Once you have your box and your wheels, you need to find the "beltline." This is the horizontal line that separates the metal body from the glass windows (the greenhouse). In classic car design, this line is everything. On a 1969 Dodge Charger, that beltline has a distinct "kick-up" over the rear wheels. It gives the car a muscular, crouching stance.

Basically, you're looking for the gesture.

- The Overhang: Look at how much metal sits in front of the front wheels and behind the rear wheels. Classics usually have massive rear overhangs.

- The A-Pillar: This is the post between the windshield and the side windows. On older cars, these are incredibly thin compared to the chunky pillars on cars today.

- The Crown: The top of the fenders usually sits higher than the hood. This creates a "valley" in the center of the car.

Why Chrome is Actually a Mirror

One of the most intimidating parts of learning how to draw a classic car is the chrome. Bumper, mirrors, trim—it’s all everywhere. But here’s the trick: chrome isn't silver. Chrome is whatever is around it. If the car is outside, the top half of the chrome bumper is reflecting the blue sky. The bottom half is reflecting the brown dirt. There is usually a very sharp, high-contrast "horizon line" right in the middle of the chrome piece.

Don't use a blending stump yet. Keep your darks dark and your lights white. The reason classic cars look "expensive" in drawings is the level of contrast. If you smudge everything into a gray mess, the metal looks like plastic. You want "hard edges" where the sky meets the earth in the reflection of the fender.

✨ Don't miss: Can You Use Target Gift Cards at Starbucks? The Frustrating Reality of Where Your Money Works

The Mid-Engine Proportional Shift

If you decide to draw a mid-engine classic, like a Lamborghini Miura or a De Tomaso Pantera, everything you just learned about proportions changes. The "cabin" moves forward. The space between the back of the door and the rear wheel grows significantly to house the engine.

I see people try to draw a Miura with front-engine proportions all the time. It ends up looking like a weird Corvette. You have to measure the "dash-to-axle" ratio. On a front-engine car, there’s a lot of distance between the dashboard and the front wheels. On a mid-engine car, that distance is tiny. It’s these small, geometric truths that separate a "drawing of a car" from a "portrait of a machine."

Handling the Curves of the "Coke Bottle" Style

In the mid-1960s, designers moved away from the "pancake" look of the 50s and toward the "Coke Bottle" shape. This means the car is wide at the fenders, narrows at the doors, and widens again at the rear.

To draw this, you need to imagine the car’s "section lines." If you sliced the car in half like a loaf of bread, what shape would that slice be? At the door, it’s a vertical oval. At the rear fender, it’s a much wider, more aggressive curve. Drawing these light "contour lines" over your box helps you "wrap" the metal skin over the frame. It’s much more like sculpting than drawing.

Common Pitfalls That Kill Your Realism

Most people draw the windows too big. We spend our lives looking out of car windows, so our brains think they are huge. On a chopped 1950 Mercury Lead Sled, the windows are tiny slits. If you draw them to "human scale," you lose the car's attitude.

Another thing is the "stance." A classic car shouldn't look like it's floating. There’s a weight to it. The tires should have a very slight bulge where they hit the pavement. The shadow underneath the car—the "core shadow"—should be the darkest part of your entire drawing. This "grounds" the car. Without a heavy occlusion shadow directly under the chassis, your 3,000-pound machine will look like a balloon.

Taking Your Sketch to the Next Level

You've got the box. You've got the ellipses. You've mapped the beltline and the chrome reflections. Now you need to think about line weight.

Do not use the same pencil pressure for the whole drawing. Use a heavy, dark line for the underside of the car and the areas in deep shadow. Use a very light, almost invisible line for the top surfaces where the sun is hitting the metal. This "tells" the viewer's eye where the light source is without you having to shade every single inch of the paper.

Actionable Next Steps for Mastery

- Print a photo of a car and a ruler. Don't draw yet. Just measure. How many "wheels" long is a Porsche 911 compared to a Lincoln Continental? You’ll be shocked at the difference.

- Practice 50 ellipses a day. Seriously. Fill a page. If you can't draw a clean ellipse, you can't draw a classic car. It’s the "scales" of the automotive art world.

- Start with the "Side View" silhouette. Before jumping into 3D perspective, master the profile. If you can't get the silhouette right, the perspective won't save you.

- Study "Industrial Design" sketching. Look up designers like Frank Stephenson or Ian Callum. See how they use "marker sweeps" to indicate form. They don't draw every detail; they draw the idea of the detail.

- Use a "T-Square" or a straight edge. Even the pros use tools. There is no shame in using a ruler for the long, straight lines of a 1960s rocker panel.

The goal isn't perfection on the first try. Your first ten car drawings will probably look a bit wonky. Maybe the wheels will look like eggs or the roof will look smashed. That’s fine. The trick is to keep your construction lines light so you can correct them as you go. Once you understand the underlying skeleton of the vehicle, you’ll realize that every classic car is just a series of beautiful, intersecting mathematical curves.

Find a photo of a 1963 Split-Window Corvette. Look at the center line that runs from the nose to the tail. Try to draw just that one line in perspective. That’s your starting point. From there, everything else is just building onto that spine.

Resources for Further Study

- "How to Draw" by Scott Robertson: The bible of technical perspective.

- The "Line of Action" concept: Common in character design but vital for cars.

- Car Design News: Good for seeing how modern pros still use these "classic" proportions.

Mastering the art of the automobile takes time. It’s a mix of engineering knowledge and artistic flair. But once you get that first "perfect" perspective sketch down, you’ll never look at a parking lot the same way again.