You’ve seen the photos. Those long-exposure shots where the sky looks like it’s literally cracking open to reveal a glowing, purple-and-gold river of stardust. It’s breathtaking. Naturally, you grab your brushes or your digital tablet because you want to capture that. But then, ten minutes in, your canvas looks like a spilled bottle of bleach on a navy rug.

It’s frustrating.

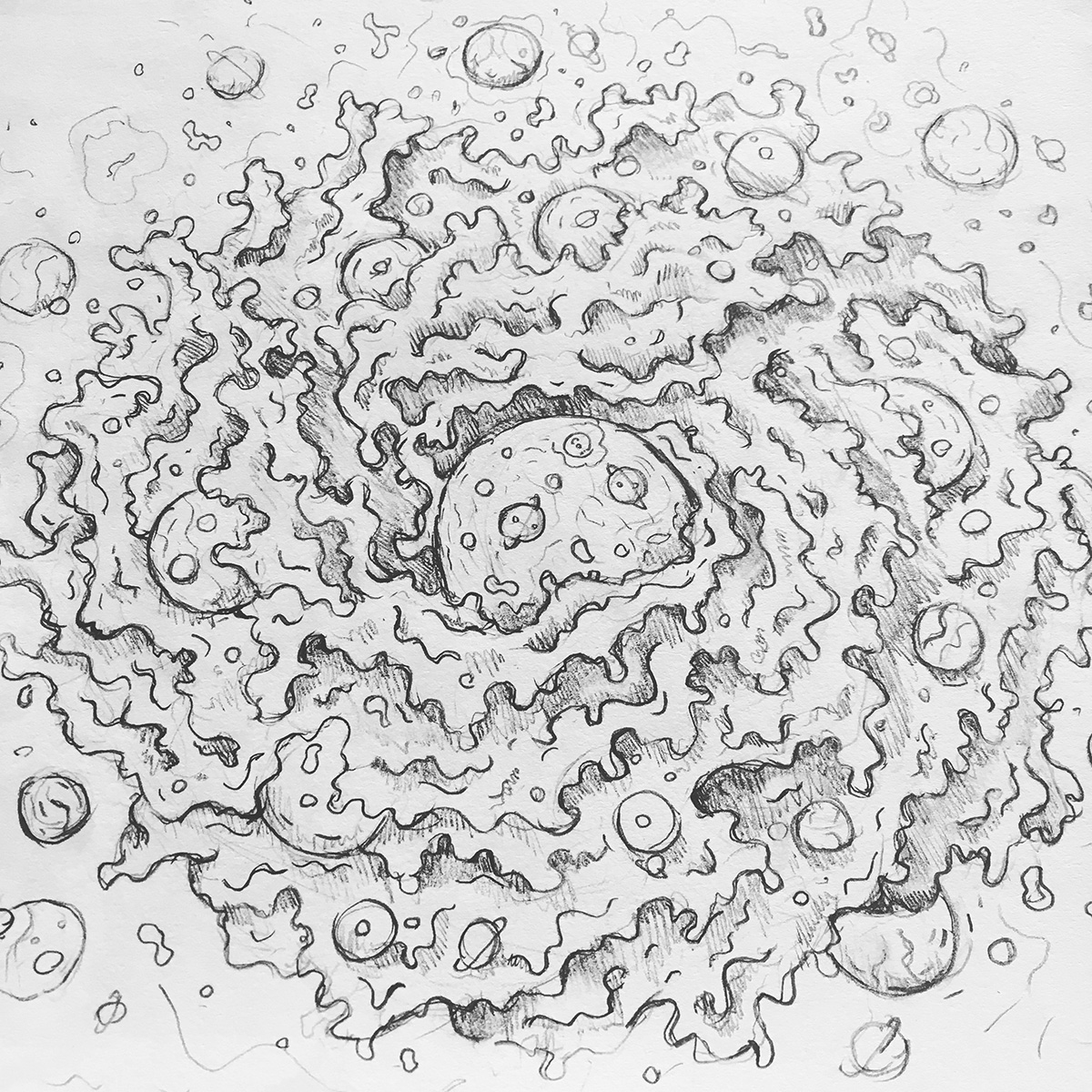

Learning how to draw the milky way isn't actually about drawing stars. That’s the first mistake almost everyone makes. They start dotting the page with white ink. Honestly, if you do that, you’re just making a polka-dot pattern. Real galactic art is about the dust. It’s about the gaps. It’s about the terrifyingly vast pockets of nothingness that allow the light to actually mean something.

Most people think of the galaxy as a bright object. In reality, it’s a structural mess of cosmic gas, interstellar dust, and billions of distant suns that our eyes perceive as a hazy "milk" across the sky. To draw it well, you have to think like an astronomer and act like a watercolorist—even if you’re working in Procreate or oil paints.

The Anatomy of the Great Rift

Before you touch a pencil, you have to understand what you’re looking at. When we talk about how to draw the milky way, we are usually talking about the Galactic Center. This is the brightest part of the galaxy, located in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius.

There’s this thing called the Great Rift. It’s a dark band of cold gas and dust that obscures the bright center of the galaxy. If you don't include this "dark river," your drawing will look flat. NASA’s Hubble and James Webb images show us that these dark clouds are just as textured as the glowing ones. They have "pillarlike" structures. They have wisps.

You need to lay down your darkest values first. If you’re using paper, this means a deep, almost-black indigo. Don’t use pure black. Pure black is dead. It has no soul. Mix a little bit of Phthalo Blue or Alizarin Crimson into your black to give it a "temperature." Space is cold, but the light within it is warm.

Layering the Glow Without Making a Mess

Start with the "haze."

If you're working with watercolors, this is a wet-on-wet technique. You soak the paper, then drop in very faint pigments of violet, magenta, and a tiny bit of ochre. The colors should bleed. They should be messy. In the digital world, this is where you use a soft airbrush on a "Linear Dodge" or "Add" layer at about 10% opacity.

One big secret? The Milky Way isn't just blue.

If you look at the work of professional astrophotographers like Babak Tafreshi, you’ll notice an incredible amount of yellow and green airglow. Most beginners stick to blue and purple because that’s what "space" looks like in movies. But real space is a muddy, beautiful kaleidoscope.

Add some warmth. A little bit of burnt sienna or gold near the core of the galaxy makes the whole piece feel more "organic." It stops it from looking like a screensaver.

Why Texture Matters More Than Precision

Stop trying to be perfect.

The universe is chaotic. When you're figuring out how to draw the milky way, your best friend is a dry brush or a sea sponge. If you’re digital, find a "noise" or "splatter" brush. You want "grit." The stars aren't perfect circles; they are tiny pinpricks of light that often blur together into a luminous fog.

- The Base Layer: Deep darks, but not flat black. Use "near-blacks."

- The Mid-Tones: Soft purples and magentas. This is the "gas."

- The Core: Warm yellows and whites. This is where the density is highest.

- The Dark Nebula: Re-inserting the "Great Rift" with even darker, sharper edges to create depth.

The Star Splatter Technique

Okay, let’s talk about the actual stars.

Don't draw them one by one. You’ll lose your mind. And it’ll look fake.

The "flick" method is the gold standard for traditional artists. Take an old toothbrush, dip it in slightly thinned white acrylic or gouache, and flick the bristles with your thumb. It creates a random distribution of sizes. Some will be big, some will be microscopic. That randomness is what our brains interpret as "natural."

For the "hero stars"—those big, bright ones that stand out—use a toothpick. Just a few. If you add too many big stars, the eye doesn't know where to look. You want the viewer’s eye to follow the "path" of the Milky Way, not get stuck on a single bright dot.

Common Mistakes That Kill the Vibe

I’ve seen a lot of people try to draw the galaxy, and they usually fail because they make the edges too sharp.

Space doesn't have edges.

Everything should fade into the "nothingness" of the peripheral sky. If your Milky Way looks like a floating cigar or a bright sausage in the sky, you need to blend your edges out. Use a clean, damp brush to pull the color into the black background. It should be a gradient so subtle you can barely tell where the galaxy ends and the void begins.

Another thing? Avoid the "Glitter Bomb" effect.

Not every part of the sky is filled with stars. If you look at the actual night sky, there are "empty" patches. These gaps are essential. They provide visual "rest" for the viewer. If your entire canvas is covered in white dots, it’s not a galaxy; it’s just noise.

Digital vs. Traditional: Different Paths to the Same Stars

If you're using Procreate or Photoshop, use layers. Please.

Put your "Glow" layer on a different setting than your "Star" layer. Using the "Gaussian Blur" tool on a duplicate layer of your stars can create that "halation" effect you see in high-end photography. It makes the stars look like they’re actually burning.

📖 Related: The Real Brit Fit: Why the UK’s Fitness Identity is Moving Beyond the Gym

For traditional painters, it’s all about patience. You have to let layers dry. If you try to flick white stars onto wet purple paint, you’ll just get light purple blobs. Wait. Let it dry completely. Then flick. The crispness of the white paint on top of the dark background is what creates the illusion of infinite distance.

Beyond the Canvas: Understanding Your Subject

There is a psychological component to how to draw the milky way.

You are trying to represent something that is 100,000 light-years across on a piece of paper that is maybe 12 inches wide. That’s a massive scale shift. To make it feel "big," you need to include something for scale.

A silhouette of a pine tree. A tiny mountain range at the bottom. A lone person standing on a hill.

By putting something "human-scale" in the foreground, you trick the viewer’s brain into realizing how gargantuan the background is. It’s a classic trick used by Romantic-era painters like Caspar David Friedrich, and it works perfectly for space art.

Practical Steps to Finish Your Piece

Don't just stop when it "looks okay."

Take a step back. Literally. Walk across the room and look at your drawing. Does the Milky Way have a flow? Does it look like a river? If it looks like a static object, you might need to add some "wisps" or "tendrils" of gas that seem to be breaking off from the main body.

Check your values. If you squint your eyes, the brightest part should be the center of the galaxy, and it should gradually get darker as you move away.

Next Steps for Your Artwork:

- Audit your "Dark Rift": Ensure you have those "veins" of dark dust cutting through the bright center. This is the hallmark of a realistic Milky Way.

- Vary Star Color: Go back in with a tiny brush and add a few subtle red and blue stars. Not all stars are white. This adds a level of sophistication that screams "expert."

- Fix the Horizon: Soften the transition between the sky and whatever is on the ground. A slight "haze" near the horizon line adds atmospheric depth.

- Seal the Work: If using charcoal or pastels, use a fixative immediately. These mediums smudge easily, and a single thumbprint can ruin your delicate star fields.

- Practice the "Flick": If you're nervous about the toothbrush method, practice on a scrap piece of black paper first. Control the distance; the further away you are, the finer the "star dust" will be.

The beauty of the galaxy is its imperfection. It’s a messy, swirling, ancient structure of light and shadow. Stop trying to make it neat, and start trying to make it feel vast. Once you stop worrying about individual stars and start focusing on the flow of the gas and the "silence" of the dark spots, your art will transform from a craft project into a window to the cosmos.