It’s easy to dismiss John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath as that dusty, thick paperback your high school English teacher forced you to lug around. Honestly, that's a shame. When the novel first dropped in 1939, it didn't just sit on shelves; it practically set the country on fire. It was banned, burned in public squares, and denounced on the floor of Congress as "communist propaganda." Why? Because it told a truth that people in power weren't ready to hear.

Steinbeck wasn't just writing a "sad story" about the Great Depression. He was reporting from the front lines of a humanitarian disaster. He spent months living in federal migrant camps, traveling with families who had lost everything to the Dust Bowl. He saw the starvation. He saw the corporate greed. Then, he turned it into a 200,000-word gut-punch that still feels weirdly relevant in our era of housing crises and economic shifts.

The Brutal Reality Behind the Joad Family

The story follows the Joads, a family of sharecroppers kicked off their Oklahoma farm. They head to California because they've seen handbills promising high wages and plenty of work. But California isn't the Promised Land. It’s a place where "Okies" are treated like dirt and the surplus of labor is used to drive wages down to pennies.

Steinbeck used a clever, alternating structure. One chapter follows the Joads; the next is a "general" chapter describing the broader state of the country. This isn't just a stylistic choice. It forces you to see that the Joads aren't unique. They are one of 300,000 people moving west.

Why the "Dust" was a Man-Made Disaster

People think the Dust Bowl was just bad luck with the weather. It wasn't. Decades of poor farming practices, like deep plowing the virgin topsoil of the Great Plains, destroyed the native grasses that held the moisture. When the drought hit, there was nothing to keep the dirt on the ground. The wind literally blew the Midwest away. Steinbeck captures this in the opening pages—the "red sun" and the dust that "settled on everything." It’s a terrifying image of ecological collapse that sounds a lot like the climate warnings we hear today.

The Myth of the California Dream

The "handbills" were a scam. Steinbeck explains how growers would print 100,000 leaflets for 1,000 jobs. Why? If 5,000 people show up for five jobs, the owner can pay whatever he wants. If a man won't work for twenty cents, the next starving guy will work for fifteen. This is the "grapes of wrath" brewing—the growing resentment and anger of people who are being squeezed for every last drop of labor while their kids go hungry.

Fact vs. Fiction: Was It Really That Bad?

Critics at the time, specifically the Associated Farmers of California, called Steinbeck a liar. They claimed the conditions in the migrant camps weren't that bad. Steinbeck countered by pointing to his journalism. Before the novel, he wrote a series of articles called The Harvest Gypsies for the San Francisco News.

📖 Related: SpongeBob and Mr Krabs Reaching New Heights: Why Their Dynamic Still Drives Animation

He had seen it.

The "Hoovervilles"—shantytowns made of cardboard and scrap metal—were real. The "Starvation under the orange trees" was real. In one famous scene, a woman dies because she can't get basic medical care. Steinbeck based these moments on actual reports from camp managers like Tom Collins, the man to whom he dedicated the book.

The Censor's Fury

The book was so controversial that the Kern County Board of Supervisors banned it from public libraries for years. They hated how Steinbeck portrayed the local law enforcement and the wealthy landowners. Even Eleanor Roosevelt had to step in. She visited the camps herself and told the press, "I have never thought The Grapes of Wrath was exaggerated." When the First Lady has to verify your fiction, you know you've hit a nerve.

Tom Joad and the Ghost of Social Justice

"I'll be all around in the dark. I'll be ever'where—wherever you look."

That's Tom Joad's famous speech toward the end. It's become a symbol of the American worker's spirit. But look at Tom's journey. He starts the book as a man just trying to get by, fresh out of prison for killing a guy in a bar fight. He’s selfish. He's practical. By the end, through the influence of the ex-preacher Jim Casy, he becomes something else. He realizes that a single person doesn't matter as much as the "one big soul" of humanity.

It’s a radical transformation.

Jim Casy himself is the moral heart of the book. He gives up the pulpit because he can't reconcile old-school religion with the suffering he sees. He realizes that "holy" isn't something you find in a church; it’s something you find in people helping each other. When he is killed for trying to organize a strike, he dies a martyr's death, echoing the words of Christ: "You don't know what you're a-doin'."

The Ending Everyone Still Argues About

We have to talk about Rose of Sharon.

✨ Don't miss: Why Westworld the TV series Still Messes With Our Heads

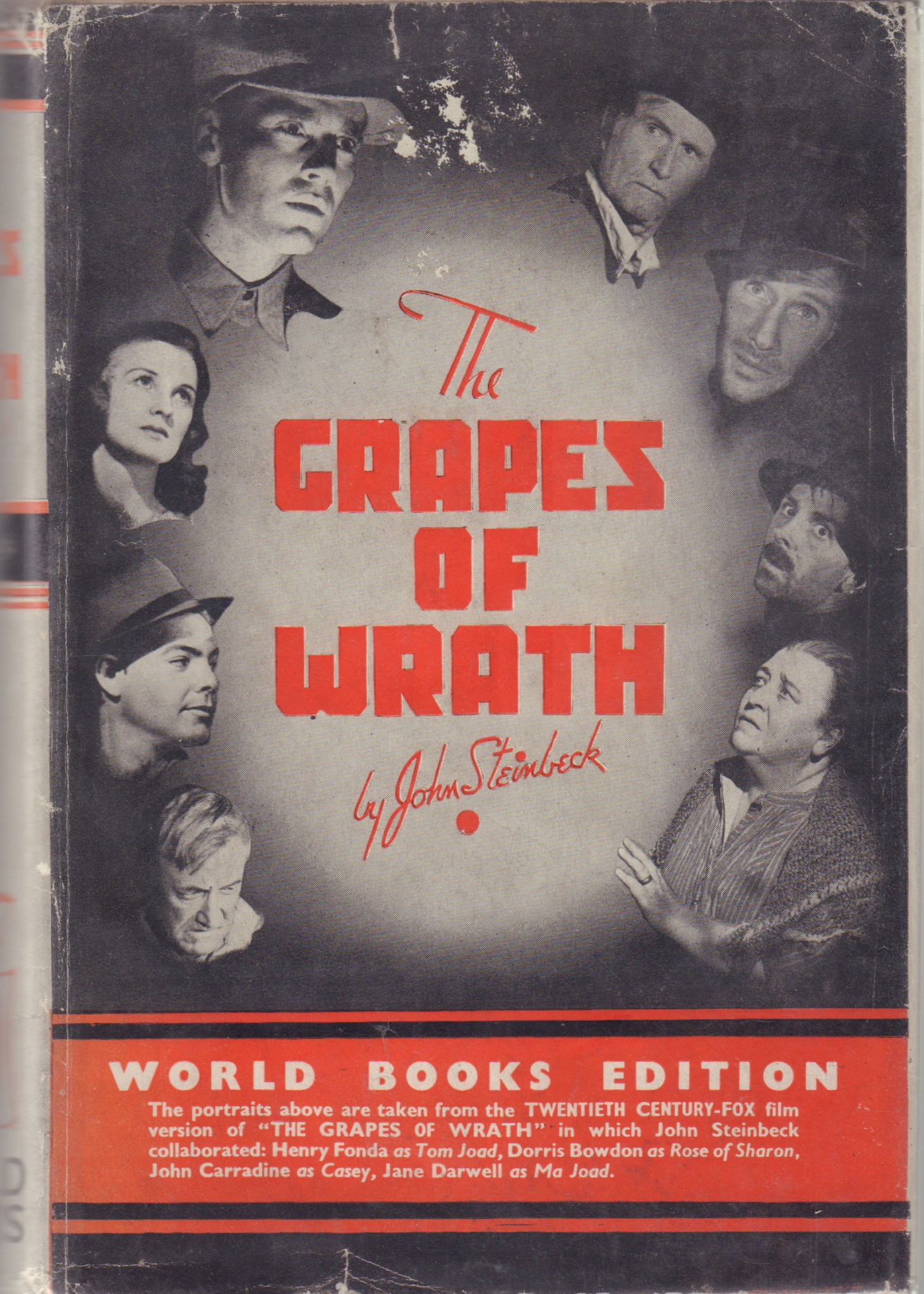

The ending of John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath is one of the most shocking in American literature. If you haven't read it, or if you only saw the 1940 John Ford movie (which changed the ending entirely), it’s a doozy. After her baby is stillborn, Rose of Sharon uses her breast milk to save a starving man she doesn't even know.

It’s graphic. It’s uncomfortable. It’s beautiful.

Steinbeck’s editors begged him to change it. They thought it was too much. But Steinbeck refused. He argued that the whole point of the book was the transition from "I" to "We." The family has lost everything—their home, their truck, their dog, their elders, and finally, their newest member. Yet, in that moment of total loss, they still find a way to give. It’s the ultimate act of human solidarity.

How to Read Steinbeck Today (Without Falling Asleep)

If you're going to dive into this beast, don't treat it like a chore. Read it for the anger. Read it for the descriptions of the landscape that feel almost cinematic.

- Skip the Preconceptions: Forget the black-and-white movie. The book is much grittier and more politically charged.

- Watch the "Intercalary" Chapters: Those short, weird chapters between the Joad family's story? Those are the keys to the kingdom. They explain the economics of the 1930s better than any textbook.

- Listen to the Language: Steinbeck spent years listening to how these people actually talked. The dialect isn't just "flavor"; it's an act of respect for a class of people who were usually ignored or mocked.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

Reading a classic isn't just about checking a box. It’s about understanding the machinery of the world. Here’s what you can actually take away from Steinbeck's masterpiece:

- Question the Narrative: Just like the "handbills" in the 1930s, examine the modern promises of "economic opportunity" that seem too good to be true.

- Look for the "Big Soul": In times of crisis, the only thing that works is community. The Joads survived as long as they did because they shared what little they had.

- Understand Displacement: The Joads were internal refugees. Understanding their story helps build empathy for the millions of people globally who are currently displaced by war, climate, or economic collapse.

The book doesn't have a happy ending. The Joads aren't "saved" by a miracle. They are just still there, enduring. That's the point. Steinbeck didn't write a fairy tale; he wrote a mirror. If we don't like what we see in it, that's on us, not the book.

To truly appreciate the depth of this work, consider visiting the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California. Seeing the actual "Old 1928 Hudson" truck used in the film and the journals Steinbeck kept while writing can bridge the gap between 1939 and now. You'll realize that while the clothes and the cars have changed, the struggle for dignity hasn't moved an inch.

Next Steps to Deepen Your Understanding:

- Read The Harvest Gypsies, Steinbeck's non-fiction reports that served as the raw data for the novel.

- Compare the book's ending to the 1940 film adaptation to see how Hollywood sanitized the political message.

- Research the "Farm Security Administration" photographs by Dorothea Lange to see the real faces of the people Steinbeck was writing about.