Walk into any classroom in America and you’ll see it. That grainy, black-and-white sketch of angry men in Mohawk disguises dumping crates into a harbor. It’s iconic. Honestly, no taxation without representation images are basically the original political memes, even if they didn't have the internet back then. They tell a story of a specific kind of frustration that feels weirdly modern. You’ve probably seen the "Join or Die" snake or those woodcut prints of the Boston Massacre. They weren't just art; they were weapons.

The Power of the Visual Protest

Back in the 1760s, literacy wasn't universal. If you wanted to start a revolution, you couldn't just write a 50-page manifesto and hope everyone read it. You needed pictures. Paul Revere—yeah, the "midnight ride" guy—was actually a pretty savvy engraver. His depiction of the Boston Massacre is one of the most famous no taxation without representation images in existence, but here’s the kicker: it was total propaganda.

The image shows British soldiers firing in a neat line into a peaceful crowd. In reality? It was a chaotic mess in the snow, and the colonists were heckling the guards. But Revere knew that a stark, violent image would sell the "tyranny" narrative better than a nuanced report. It worked. People saw that image and felt the blood boil. It’s a classic example of how visual media shapes history more than the actual facts sometimes do.

Why We Still Look at These Images

Why do we care about a 250-year-old woodblock print? Because the sentiment hasn't actually gone away. You see these images pop up on license plates in Washington D.C. today. "Taxation Without Representation" is literally stamped on their cars because they have no voting member in Congress.

It’s a living grievance.

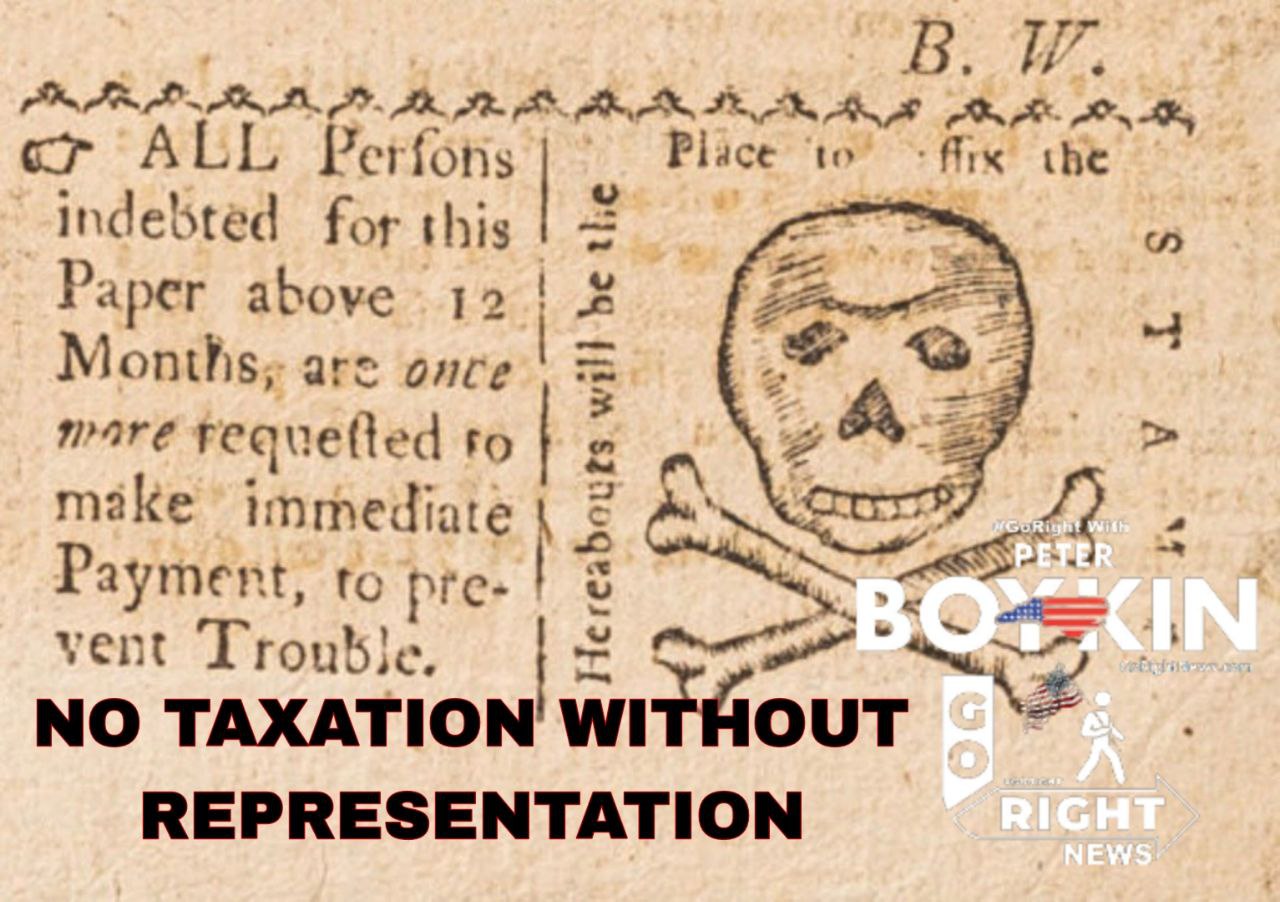

When you look at the no taxation without representation images from the Stamp Act era, you see skulls and crossbones printed where the tax stamp was supposed to go. It was a "kinda" punk rock move for the 18th century. The colonists were basically saying, "This tax will be the death of us." It’s visceral. It’s visual shorthand for "I’m being ignored by my government."

The Most Famous Visuals of the Rebellion

There are a few heavy hitters you’ll find whenever you search for these visuals.

The Magna Britannia Her Colonies Reduced. This one is wild. It’s an image attributed to Benjamin Franklin. It shows Britannia (the personification of Britain) with her limbs cut off. The limbs are labeled with the names of the colonies. It’s a grisly, metaphorical way of saying that by taxing the colonies into oblivion, Britain was literally dismembering itself. It’s dark. It’s effective.

Then you have the Join, or Die cartoon. Most people think it was created for the American Revolution. It actually wasn't. Franklin drew it in 1754 for the Seven Years' War, but it got recycled during the Stamp Act crisis. It’s the ultimate "viral" image. A snake chopped into pieces representing the divided colonies. The message? Get it together or get crushed. Simple.

Modern Interpretations and Digital Archives

If you're looking for high-quality no taxation without representation images for a project or just out of curiosity, the Library of Congress is the gold standard. They have high-resolution scans of the original broadsides. You can actually see the texture of the paper and the ink bleeds.

Digital archives like the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History also host massive collections. You’ll find things like:

- Political cartoons from London (yes, some Brits actually agreed with the colonists).

- Satirical prints of "The Able Doctor," where Britain is force-feeding tea down America's throat.

- The "Tea-Tax Tempest," which shows the world literally blowing up over a teapot.

It’s funny how the humor hasn't changed much. We still use political cartoons to mock the people in power. The only difference is now we use iPads instead of copper plates and acid.

The Misconception of "Representation"

Here is something most people get wrong. When the colonists shouted about "No Taxation Without Representation," they weren't necessarily asking for a seat in Parliament. Many actually feared that if they did get a few seats, they’d be outvoted anyway and then have no excuse to complain.

The images from this time reflect a desire for local control. They wanted their own provincial assemblies—the people who actually lived in the mud with them—to be the ones deciding the taxes. It wasn't just about the money. It was about who had the right to take it.

The no taxation without representation images often show the "Stamp Man" or tax collectors being tarred and feathered. It was brutal. It wasn't just a polite disagreement. These images were meant to intimidate. If you were a British official and you saw a print of a guy being covered in hot tar, you got the message pretty quickly.

How to Use These Images Today (Ethically and Legally)

Since most of these images were created in the 1700s, they are firmly in the public domain. You can use them for almost anything without worrying about a lawsuit from Paul Revere’s estate.

- Check the Source: Always try to find the original scan from a museum or university library to ensure you're getting the real deal and not a modern "reimagining."

- Understand the Context: Before using the "Join or Die" snake, remember its origins. It has been co-opted by dozens of different political movements over the centuries.

- High Res Matters: If you're printing these for a classroom or a poster, look for TIFF files. JPEGs of old woodcuts often lose the fine line detail that makes them look authentic.

History isn't just a bunch of dates. It's a vibe. The no taxation without representation images we still use today are the leftovers of a very loud, very angry, and very visual argument. They remind us that even before the age of cameras, people knew that if you wanted to change the world, you had to make sure people could see what you were talking about.

✨ Don't miss: Botella de Rémy Martin: Por qué no todo el coñac se crea igual

Actionable Next Steps

If you're doing a deep dive or building a presentation, don't just grab the first thumbnail you see on a search engine.

- Visit the Library of Congress online catalog. Search for "Stamp Act" or "Boston Tea Party" specifically under the "Prints and Photographs" section.

- Analyze the symbolism. Look for the "Liberty Tree" in the background of 18th-century prints. It was a real place in Boston and became a massive symbol in the art of the time.

- Compare British vs. American prints. Seeing how London artists depicted the "rebellious children" in the colonies versus how the colonists saw themselves provides a much more complete picture of the conflict.

The power of these images lies in their grit. They weren't meant to be pretty. They were meant to be felt. Whether it's a skull on a stamp or a snake in pieces, they still carry that same "don't tread on me" energy that defines a huge part of the American identity.