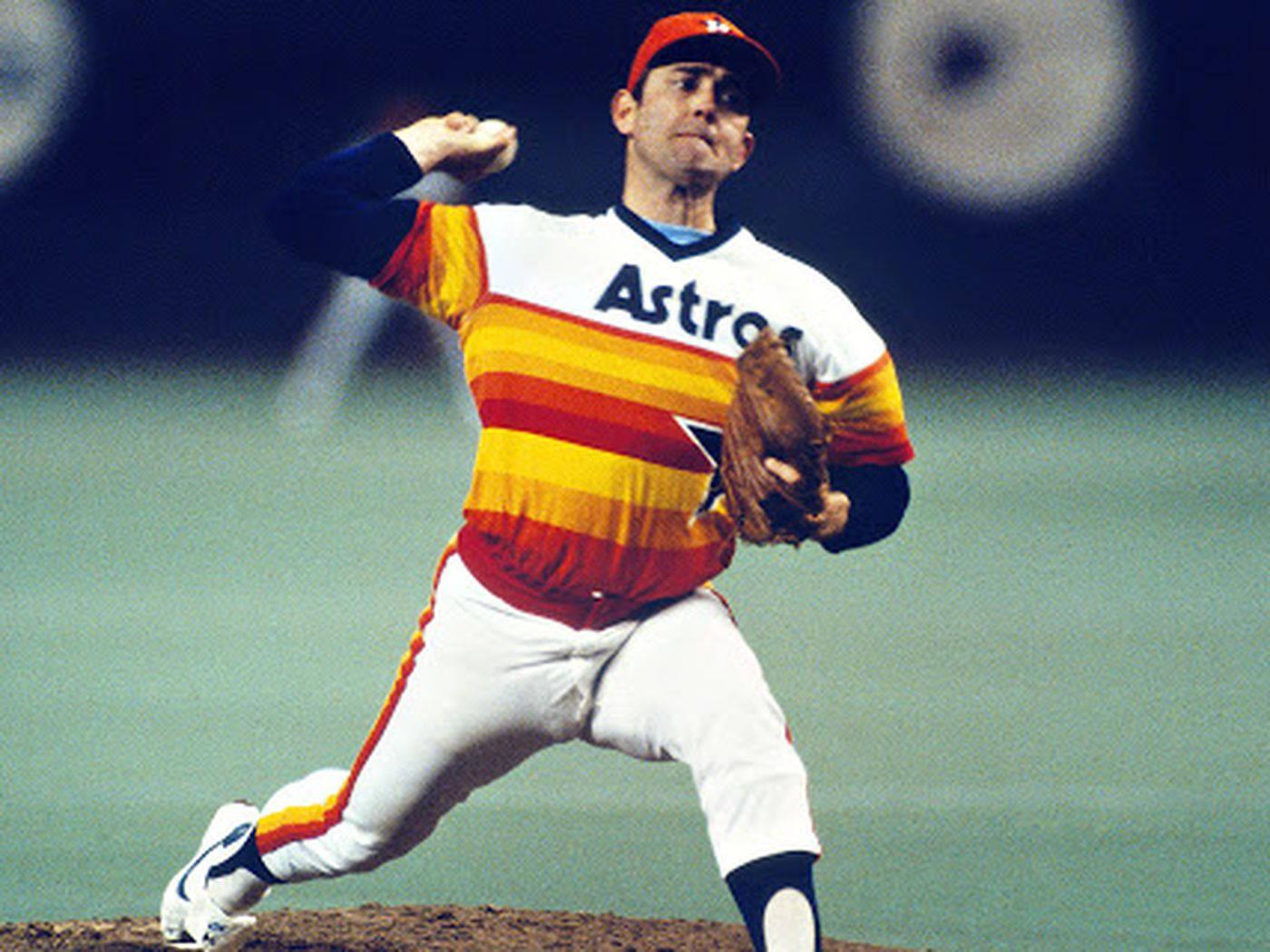

Nolan Ryan throwing a baseball felt like a physical event you could hear before you saw it. If you were sitting in the lower boxes of the Astrodome in the early 1980s, you didn't just see the "Ryan Express"—you heard the catcher’s mitt pop with a sound like a small-caliber rifle. People still talk about it. They talk about the heat, the sweat, and the rainbow-striped jerseys that somehow became iconic because he was wearing one.

Honestly, the Nolan Ryan Houston Astros era is one of the most misunderstood stretches in baseball history.

💡 You might also like: The Philadelphia 76ers Toronto Raptors Rivalry: Why This Matchup Always Feels Like a War

Most fans remember the Mets years for the 1969 ring or the Rangers years for the bloody lip and the seventh no-hitter. But Houston? That’s where the legend actually solidified into something superhuman. He spent nine seasons there, from 1980 to 1988. That’s the longest he stayed with any single team. It was a homecoming, a financial earthquake, and a statistical anomaly all rolled into one.

The Million Dollar Man Comes Home

When Ryan signed with the Houston Astros in November 1979, the sports world basically melted down. He was a Texas boy from Alvin, just about 30 miles down the road from the Dome. He famously said he’d have bought his own bus ticket to pitch for the Astros. Instead, he got a four-year, $4.5 million contract.

That made him the first million-dollar-a-year player in Major League history.

It’s hard to fathom now when mid-tier relievers make $10 million, but in 1980, that number was astronomical. People thought the Astros were insane. California Angels GM Buzzie Bavasi famously let him walk, saying he could replace Ryan with "two 8-7 pitchers."

He was wrong. Dead wrong.

That Ridiculous 1981 No-Hitter

By the time 1981 rolled around, Ryan was already a legend, but he hadn't thrown a no-no in six years. People were starting to whisper that maybe the "Express" was slowing down. Then came September 26 against the Los Angeles Dodgers.

It was the NBC Game of the Week. The whole country was watching.

Ryan didn't even have his best fastball that day. He actually had to rely on his curveball, which is sorta terrifying if you’re a batter expecting 100 mph and getting a 12-6 hammer instead. He shut down a Dodgers lineup that would go on to win the World Series that year. When he got the final out, he became the first pitcher to ever throw five no-hitters, breaking Sandy Koufax's record.

He was 34. Most guys are retiring or moving to the bullpen by then. Nolan was just getting started.

The Strikeout King vs. The Lefty

The 1980s in Houston featured a bizarre, slow-motion race between Ryan and Steve Carlton for the all-time strikeout record. They were chasing the ghost of Walter Johnson. On April 27, 1983, Ryan finally passed Johnson’s mark of 3,508.

He did it by freezing Brad Mills of the Montreal Expos with a curveball.

The rivalry with Carlton was friendly but intense. They swapped the lead back and forth like a pair of long-distance runners. Eventually, Ryan just... kept going. While Carlton’s body eventually gave out, Ryan’s arm seemed to get stronger. By the time he left the Nolan Ryan Houston Astros years behind, he had 1,866 strikeouts in an Astros uniform alone—a franchise record that still stands.

The Great 1987 "Hard Luck" Mystery

If you want to see how weird baseball can be, look at Nolan's 1987 season. It’s basically a glitch in the Matrix.

He was 40 years old. He led the National League in ERA (2.76) and strikeouts (270). Any other year, that’s a unanimous Cy Young. But because the Astros couldn't score a run to save their lives when he pitched, he finished with an 8-16 record.

💡 You might also like: Finding the Washington Wizards Store DC: Where to Score the Best Gear Locally

Think about that. You’re the best pitcher in the league by every modern metric, but you lose twice as many games as you win. It’s the ultimate "Old School vs. New School" stats argument.

Why He Actually Left

The end of the Nolan Ryan Houston Astros relationship was ugly. There’s no other way to put it.

Owner John McMullen thought Ryan was over the hill at 41. He asked him to take a pay cut for the 1989 season. Ryan, being a man of immense pride (and still possessing a 98 mph fastball), felt disrespected. He didn't just leave; he stayed in Texas and signed with the rival Rangers.

The Astros offered him about $1.3 million to stay. The Rangers offered him $1.8 million. It wasn't just about the $500k, though. It was the principle.

He went to Arlington and proceeded to throw two more no-hitters and strike out 300 batters in a season at age 42. Astros fans spent the next five years watching their greatest icon dominate in another Texas jersey. It’s still a sore spot for the older generation in Houston.

The Actionable Legacy: What We Learn From 34

Looking back at Ryan's Houston years provides some pretty clear insights for anyone looking at longevity or performance:

- Adaptability is king: When his fastball wasn't "on" in 1981, he used the curve. You can't be a one-trick pony for 27 years.

- Know your worth: He was the first million-dollar man because he knew his gravity. He filled seats. He changed the economics of the game.

- Ignore the "Age" experts: Every scout said he was done in '79, '83, and '88. He retired in '93.

If you’re ever in Houston, go look at the retired number 34 hanging in the rafters. It’s there for a reason. He wasn't just a pitcher; he was a Texas institution who proved that power doesn't have to fade with age—provided you're willing to work harder than everyone else in the room.

To really appreciate what he did, you have to look at the "Hits per 9 Innings" stat. Over his entire career, he allowed only 6.56 hits per nine. That is the lowest in the history of the game. Better than Koufax, better than Johnson, better than everyone. And a huge chunk of that dominance happened right there in the Astrodome.

Practical Next Step: If you want to see the "Ryan Express" in its prime, go find the footage of the 1986 NLCS Game 5 against the Mets. He went nine innings, allowed two hits, and struck out 12. It’s a masterclass in power pitching that still holds up under modern scouting eyes.