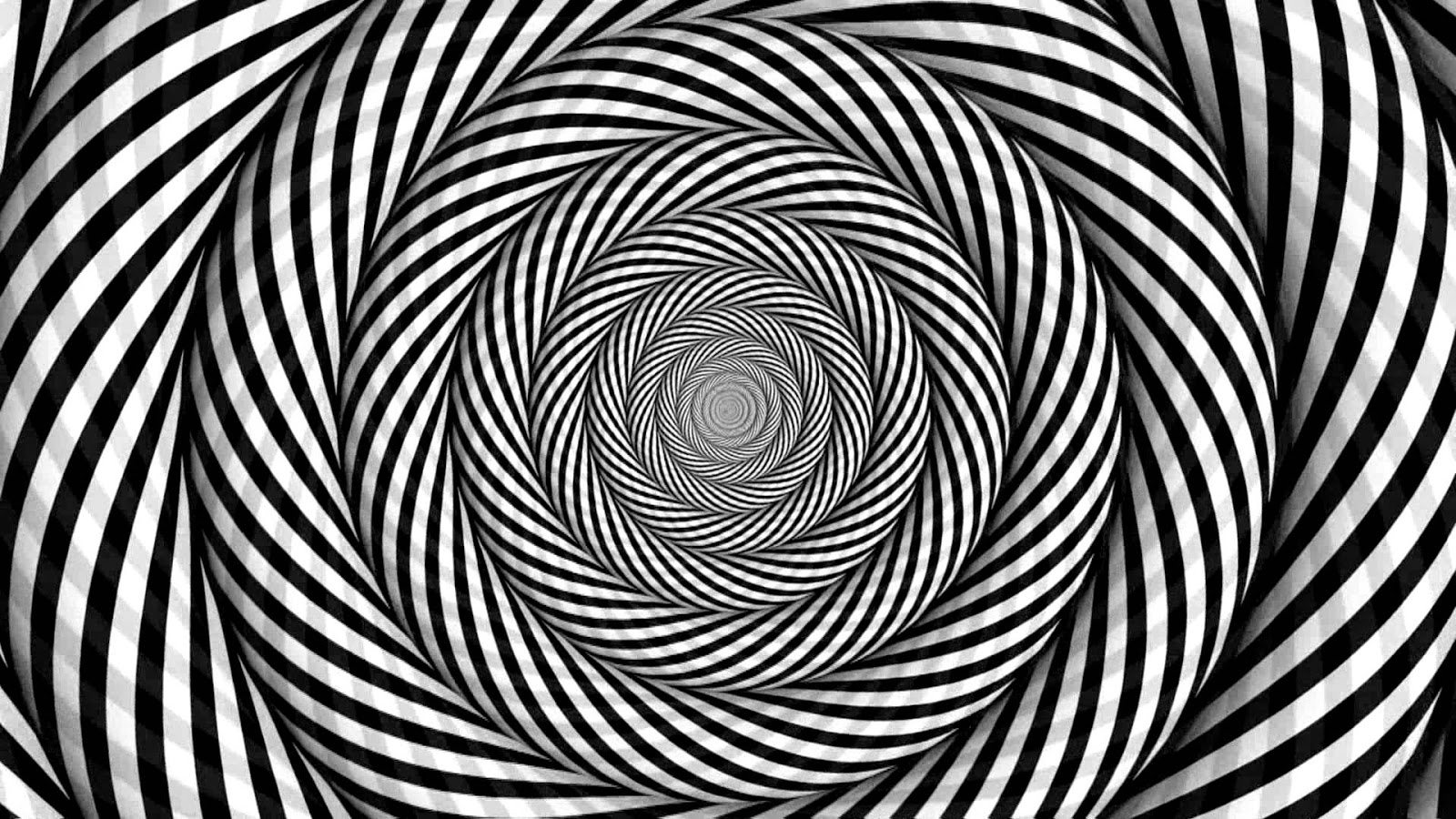

You’re staring at a screen. Or maybe a piece of paper. It’s just ink and light, strictly monochromatic, nothing fancy. Then, suddenly, the static starts to crawl. Circles rotate. Grey ghosts flicker in the intersections of a grid that isn't actually there. It’s annoying. It’s brilliant. Most of all, optical illusions in black and white prove that your eyes are basically liars, and your brain is just doing its best to keep up with the deception.

Our brains aren't cameras. Not even close. If they were, we’d see the world as it is—a collection of wavelengths and data points. Instead, we see what our biology expects to see. When you strip away color, you’re left with the raw mechanics of vision: luminance, contrast, and edge detection. This is where the real magic (and the headaches) happens.

The Brutal Simplicity of High Contrast

Color is a distraction. Honestly, it hides a lot of the "bugs" in our visual software. When you look at optical illusions in black and white, you’re interacting with the V1 area of the visual cortex. This part of the brain is obsessed with edges. It wants to know where one thing ends and another begins.

Take the Hermann Grid. You’ve seen it—a simple black grid on a white background. As you move your eyes, dark, blurry spots appear at the intersections. But if you look directly at an intersection? It vanishes. For decades, scientists like Ludimar Hermann (who discovered this in 1870) thought this was due to lateral inhibition. The idea was that receptors in the retina were competing with each other.

Actually, it’s more complicated.

Newer research suggests it’s about "S1" type cortical cells. These cells are tuned to specific sizes and orientations. When the grid doesn't match what the cells expect, your brain "fills in" the gray blobs as a sort of error correction. It’s a hack. Your brain is literally guessing what should be there because the high contrast is overwhelming its sensors.

📖 Related: DNA Test Using Hair: What Most People Get Wrong About Rootless Strands

Why Your Brain Thinks Static Is Moving

The Peripheral Drift Illusion is the one that really gets people. Think of the "Rotating Snakes" by Akiyoshi Kitaoka. Even though it's famous in color, the effect works profoundly well in grayscale. You see a series of shapes. They appear to spin. You blink, they stop. You move your eyes, they start again.

It’s a glitch in timing.

Our neurons process high-contrast edges faster than low-contrast ones. In black and white illusions, the brain receives the signal for "black" and "white" at slightly different speeds. This microscopic delay creates a "motion signal." Your brain, trying to be helpful, decides that if the signals are arriving at different times, the object must be moving. It’s not. You’re just faster than your own neurons.

The Enigma Illusion is another heavy hitter here. Isidor Leviant created this in 1981. It’s just black circles on a background of radiating lines. But when you look at it, a shimmering, circular motion appears within the rings. For years, researchers debated if this happened in the eye or the brain. In 2008, a study led by Susana Martinez-Conde at the Barrow Neurological Institute found that "microsaccades"—tiny, involuntary eye jerks—are the culprit. These tiny twitches shift the high-contrast lines across your retina, tricking the motion-processing parts of your brain into thinking there’s a flow.

The Scintillating Grid and the Failure of Focus

If the Hermann Grid is a classic, the Scintillating Grid is its chaotic cousin. Discovered by E.R. Schrader and M. Levine in 1994, it features white discs at the intersections of gray bars on a black background.

It’s wild.

Dark dots seem to "scintillate" or flash inside the white discs. But—and this is the kicker—only in your periphery. This happens because your central vision (the fovea) has a high resolution. It sees the white disc for what it is. But your peripheral vision is "low bandwidth." It tries to average out the surrounding black and gray, and in the process, it accidentally deletes the white disc, replacing it with a dark spot for a fraction of a second.

Filling in the Blanks: The Kanizsa Triangle

We hate gaps. Human beings are biologically programmed to find patterns, even when they’re missing. Gaetano Kanizsa proved this with his famous triangle. You see three "Pac-Man" shapes and some V-shapes. Immediately, your brain sees a bright white triangle sitting on top of them.

There is no triangle.

The "edges" of the triangle are called illusory contours. Your brain is so desperate for order that it creates a border out of thin air. It even perceives the "inside" of the phantom triangle as being whiter than the surrounding white paper. This is the Chevreul Illusion or Mach bands effect at work—the tendency for the brain to exaggerate contrast at boundaries to make objects stand out from their background.

The Dress and the Monochrome Reality

Remember "The Dress"? Blue and black or white and gold? While that was a color-constancy fight, it was fundamentally about how we interpret light. Optical illusions in black and white operate on the same principle of "discounting the illuminant."

If you look at the Adelson Checker-Shadow Illusion, you see two squares, A and B. Square A looks dark gray. Square B looks white. In reality? They are the exact same shade of gray.

Edward Adelson, a professor at MIT, designed this to show that our visual system isn't a light meter. We don't care about the actual amount of light bouncing off a surface. We care about what the surface is. Because square B is "in shadow," our brain assumes it must be lighter than it looks and "levels it up" in our perception. It’s a sophisticated piece of software running on 50,000-year-old hardware.

Complexity in the Absence of Hue

There's a specific kind of intensity in black and white. When you remove red, green, and blue, you're left with the "luminance channel." This channel is high-resolution. It's what we use for detail and motion. This is why black and white illusions often feel "sharper" or more aggressive than colored ones. They tap directly into the most primal parts of our sight.

Consider Mooney Faces. These are high-contrast, black and white images that look like random blobs at first. Then, suddenly, a face "pops" out. You can't un-see it. This is top-down processing. Your brain uses its library of "what a face looks like" to organize the chaotic black and white shapes. If the shapes were in color, you might get distracted by skin tones or lighting. In black and white, it’s a pure test of pattern recognition.

Practical Insights and How to Use This

Understanding how these illusions work isn't just a party trick. It has real-world legs.

- Design and UI: If you're building a website, high-contrast black and white grids can cause visual fatigue or "flicker." Softening the contrast to off-whites or dark grays can prevent the Hermann Grid effect from annoying your users.

- Safety: In low-light conditions, your vision becomes effectively monochromatic. Understanding that your brain "guesses" edges in black and white can explain why drivers sometimes miss objects or see "ghost" movements on the side of the road at night.

- Art and Composition: Photographers use "leading lines" to draw the eye, but by using high-contrast black and white patterns, you can actually dictate the speed at which someone’s eye moves across an image.

The best way to experience this is to test your own limits. Try staring at a high-contrast black and white spiral for 30 seconds, then look at the back of your hand. The "Motion Aftereffect" (the Waterfall Illusion) will make your skin appear to crawl. This happens because the neurons that detect "inward" motion get tired, leaving the "outward" motion neurons to fire unopposed.

Actionable Next Steps

- Audit Your Workspace: If you get frequent headaches while working on spreadsheets or grids, check for "scintillation." Reducing screen contrast or using a "dark mode" that utilizes deep grays instead of pure black-on-white can kill the illusion-induced eye strain.

- Test Your Contrast Sensitivity: If you find black and white illusions particularly overwhelming or if you can't see the "hidden" images in Mooney Faces, it might be worth a specific check-up. Contrast sensitivity is often a better predictor of visual health than simple 20/20 acuity.

- Mind the Night Driving: Recognize that at night, your peripheral vision is much more prone to the "drift" and "scintillation" effects mentioned earlier. Don't trust "movement" you see out of the corner of your eye in high-contrast, nighttime environments—it’s often just your brain miscalculating luminance delays.

Our vision is a constructed narrative. Black and white illusions are the cracks in that story. They remind us that what we "see" is really just a very educated guess.