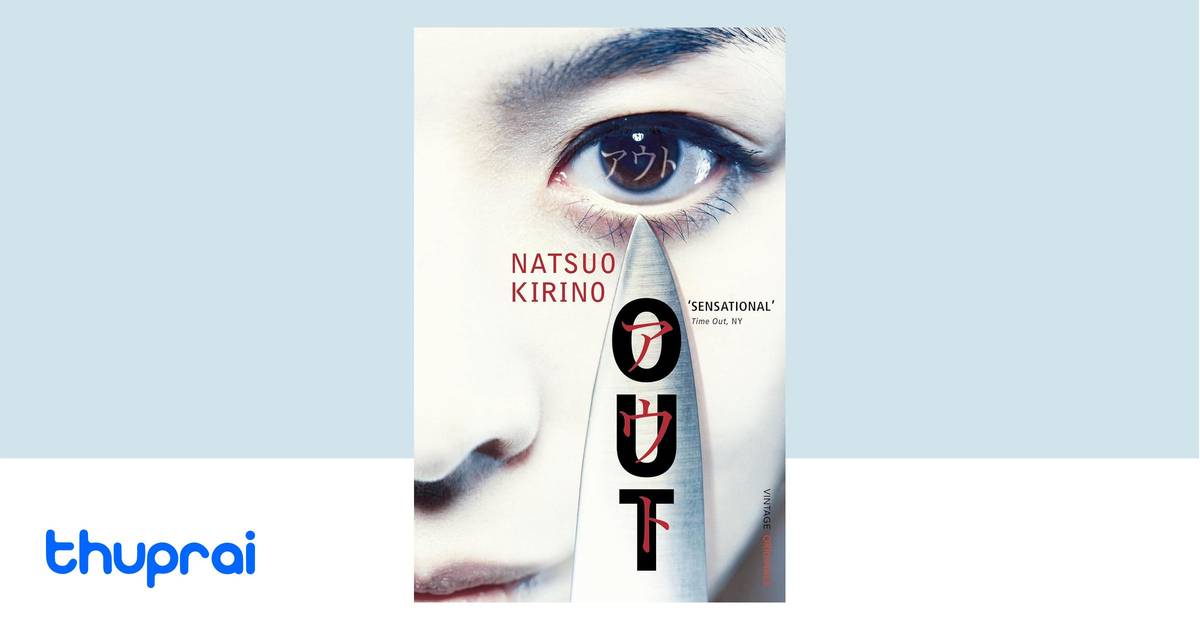

Forget the cozy mysteries where a cat helps a librarian solve a quaint murder in a tea shop. That’s not what we’re doing here. When you pick up Out by Natsuo Kirino, you’re stepping into a world of grease, exhaustion, and the kind of bone-deep desperation that makes "good" people do things they can’t ever take back.

It’s brutal. It's messy. Honestly, it's one of the most unapologetic pieces of feminist noir ever written.

Published in Japan in 1997 and translated into English by Stephen Snyder in 2003, this novel didn't just break the mold of Japanese crime fiction; it smashed it with a hammer. Kirino doesn't care about the police procedural aspect as much as she cares about the why. Why would four women working the graveyard shift at a boxed-lunch factory in suburban Tokyo decide to help their coworker dismember her husband?

It’s not for the thrill. It’s for the survival.

👉 See also: Where Can I Watch Step Up 4? Finding the Revolution Online

The Reality of the Bento Factory

Most crime novels start with a body and a detective. Out by Natsuo Kirino starts with the suffocating smell of fried food and the rhythmic, soul-crushing movement of the assembly line. Masako, Yoshie, Kuniko, and Yayoi are the four central figures. They aren't "girlbosses" or criminal masterminds. They are tired.

Masako is the "leader," a woman who has mentally checked out of her life because her husband and son treat her like furniture. Then there’s Yayoi, who finally snaps. Her husband, Kenji, has gambled away their savings and comes home smelling of other women. When he attacks her, she strangles him.

She doesn't call the police. She calls Masako.

The brilliance of Kirino’s writing is how she makes the disposal of a human body feel like just another shift at the factory. It’s logistical. It’s work. The women take Kenji’s body to Masako’s house, and the scenes that follow are some of the most visceral descriptions in literature. Kirino describes the weight of the limbs, the sound of the saw, and the sheer physical labor of turning a person into small, unidentifiable bags of trash.

You’d think the horror would be the gore. It’s not. The horror is how easily these women adapt to it because their lives were already a series of unpleasant chores.

Why This Book Pissed Off the Critics

When Out first hit the shelves in Japan, it caused a massive stir. Some male critics were genuinely appalled. They found the violence "excessive" and the female characters "unrelatable."

That was exactly the point.

Kirino was writing against the grain of the "Yamato Nadeshiko" ideal—the traditional Japanese woman who is supposed to be demure, patient, and long-suffering. Her characters are angry. They are greedy. They are selfish. Kuniko, for instance, is a disaster of a human being. She’s obsessed with brand-name clothes, drowning in debt, and constantly making things worse for herself. She isn't a "likable" victim, and that makes her feel incredibly real.

The novel won the Mystery Writers of Japan Award, but it was also a finalist for the Edgar Award in the US, which is a big deal. It proved that the "domestic" sphere isn't just about laundry and cooking; it’s a pressure cooker.

Breaking Down the Power Dynamics

In the world of Out by Natsuo Kirino, men are mostly obstacles or threats. There’s the loan shark, Satake, who becomes a looming shadow over the second half of the book. He’s a man whose life was ruined by a previous crime, and he sees a kindred spirit in Masako.

Their relationship is... complicated. It’s not a romance. It’s a strange, violent recognition of two predators who realize they are the only ones who understand each other.

The Economic Trap of 1990s Japan

To understand Out, you have to understand the context of the "Lost Decade." Japan’s economic bubble had burst. The lifetime employment system was crumbling. Women like the ones in this book were the "part-time" labor force that kept the country running while being paid a pittance.

They are the invisible gears.

When people search for information on Out by Natsuo Kirino, they often want to know if it's a "feminist" book. The answer is yes, but not in the way you might think. It doesn't argue that women are better than men. It argues that when you push people to the absolute margins of society, they stop playing by society's rules.

Masako’s house is a perfect metaphor. It’s cold. Her son won't speak to her. Her husband ignores her. She finds more "life" and agency in the act of disposing of a corpse than she does in her marriage. That is a stinging indictment of the social structures of the time.

Satake and the Darkness of the Underworld

Let's talk about Satake for a minute. He’s the owner of a peep show who gets framed for Kenji’s murder. While the women are trying to keep their lives together, Satake is descending into a vengeful madness.

The sections of the book told from his perspective are unsettling. He is a predator who has been hunted, and his fixation on Masako drives the final act of the novel into a territory that many readers find difficult to stomach.

🔗 Read more: Who’s Behind the Masks? The Cast of The Frog and Why They’re Terrifyingly Good

I’ve talked to people who stopped reading during the final fifty pages. I get it. It’s dark. It's transgressive. But if you stop, you miss the ultimate point Kirino is making about freedom.

Masako doesn't want to go back to being a housewife. She doesn't want to be "saved." She wants to be out. Out of the factory, out of her house, out of the expectations of what a woman is supposed to be. Even if it costs her everything.

Key Themes to Watch For

- The Burden of Debt: Every character is motivated by money. It’s the invisible leash. Kuniko’s debt to the loan sharks is what eventually compromises the group.

- The Invisibility of Middle-Aged Women: Kirino highlights how society ignores women once they reach a certain age. They become "part-timers" in every sense of the word.

- The Fragility of Female Solidarity: This isn't The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants. These women turn on each other. They hide things. They use each other. It’s a realistic, gritty look at what happens when survival is the only goal.

Misconceptions About the Ending

A lot of readers get frustrated by the ending. They want justice. They want a neat resolution where the "bad" people get caught and the "good" people find peace.

That’s not Kirino’s style.

The ending of Out by Natsuo Kirino is ambiguous and arguably nihilistic. It suggests that once you’ve crossed the line, there is no "home" to return to. You are forever in the "out."

If you’re looking for a book that will make you feel warm and fuzzy, look elsewhere. But if you want a book that will make you look at your own kitchen knives differently, this is it. It’s a masterpiece of psychological suspense that still feels fresh nearly thirty years after it was written.

Actionable Next Steps for Readers

- Read the Stephen Snyder Translation: If you don't speak Japanese, this is the definitive English version. He captures the dry, detached tone of Kirino’s prose perfectly.

- Compare it to "Grotesque": If you finish Out and want more, Kirino’s other major work, Grotesque, explores similar themes of female competition and social alienation in Japan, though it’s arguably even more bleak.

- Research the "Lost Decade": Reading a bit about Japan’s economic crash in the 90s will give you a much deeper appreciation for why these characters are so desperate for a few thousand yen.

- Check Out the Film Adaptation: There is a 2002 Japanese film directed by Hideyuki Hirayama. It’s worth a watch, though, as is usually the case, the book has a depth that the movie can't quite replicate.

- Watch for the Symbolism of "Food": Pay attention to how food is described throughout the book. From the factory bento boxes to the meals the women eat, it’s always tied to their state of mind and their physical exhaustion.

Out by Natsuo Kirino remains a towering achievement in crime fiction because it refuses to blink. It looks directly at the parts of humanity we try to hide behind closed doors and asks us what we would do if we were just a little bit more tired, just a little bit more broke, and just a little bit more fed up.