You’re scrolling through Instagram or Xiaohongshu at 11 PM. Suddenly, a photo of Mapo Tofu hits your feed. It’s glistening. The chili oil looks like liquid rubies. You can almost smell the Sichuan peppercorns through the screen. But then you go to that takeout place down the street, and what you get looks... well, a bit like a beige disaster.

It's frustrating.

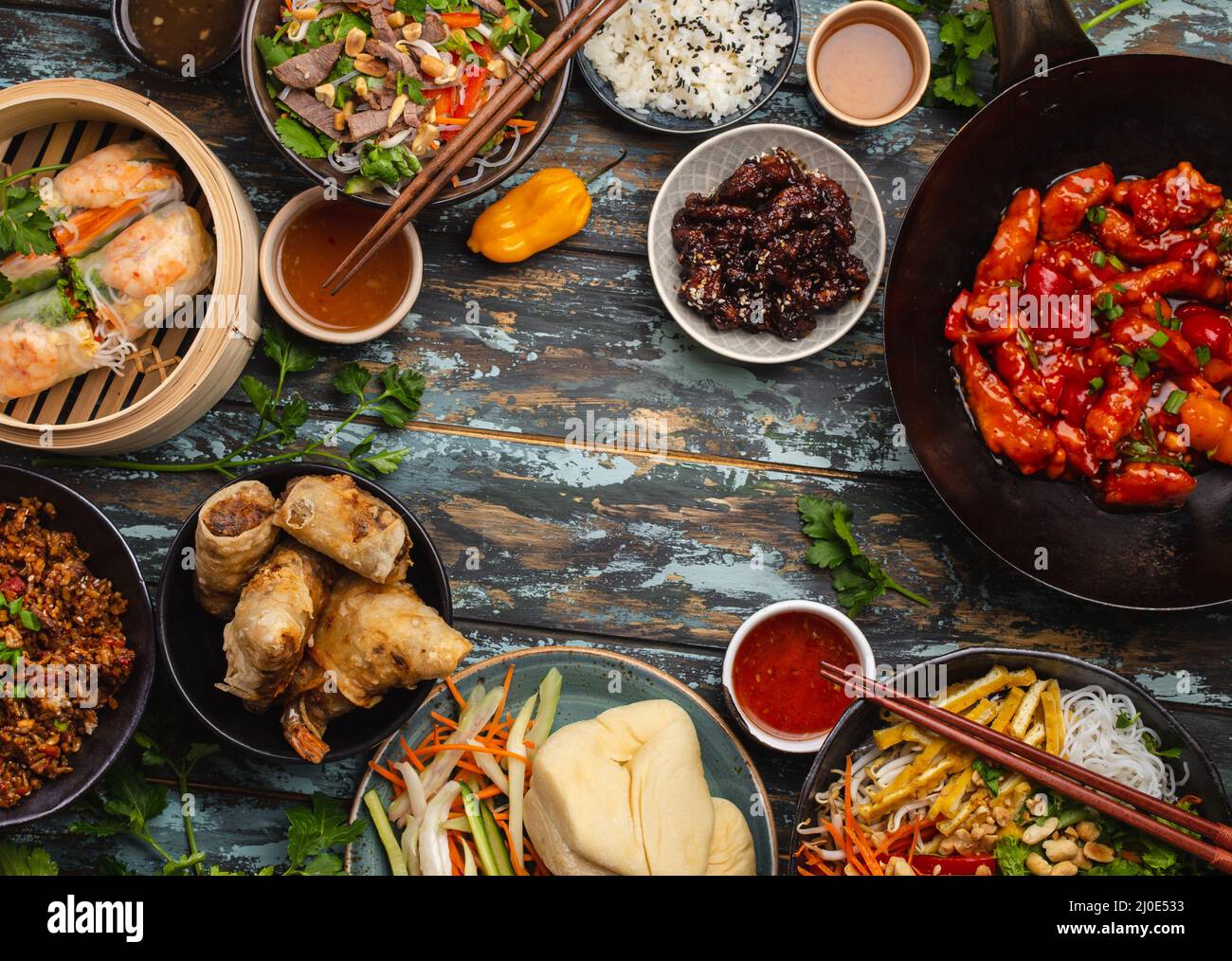

Looking at pics of chinese dishes is basically a national pastime at this point, but there is a massive gap between the "aesthetic" food photography we see online and the gritty, steam-filled reality of a working kitchen in Chengdu or Guangzhou. Honestly, if you want to understand Chinese food, you have to stop looking at the professional studio shots and start looking at the messy, high-contrast photos taken by people actually eating the food.

👉 See also: Why Your Flat Iron With Curls Never Looks Like the Salon (and How to Fix It)

The Chemistry of Why Certain Dishes Look "Bad" but Taste Great

There is a specific reason why some of the most delicious Chinese food looks terrible in photos. It’s called Meillard—well, specifically, the way soy sauce and sugar interact with high heat. Take Braised Pork Belly (Hong Shao Rou). In a professional photo, it’s a deep, glowing mahogany. In real life, under fluorescent kitchen lights? It often looks like dark, unidentifiable lumps.

The camera hates brown.

Most authentic Chinese cooking relies on "dark" flavors. Think about black vinegar from Chinkiang or fermented bean paste. These ingredients are flavor bombs, but they turn a dish into a visual swamp. If you see pics of chinese dishes where every vegetable is neon green and the sauce is perfectly translucent, you’re likely looking at a "tourist" version of the dish or a heavily styled commercial shoot.

Real food has grit.

Take "Lion’s Head" meatballs. They are oversized, tender pork meatballs steamed with cabbage. In a real photo, they look lumpy and greyish-white. But that texture? It's like clouds. If a photographer wants to make that look "good," they’ll often undercook the meat or use artificial coloring to make it pop. It ruins the soul of the dish just for the "gram."

Decoding the Visual Language of Sichuan vs. Cantonese Photos

If you want to know what you’re actually looking at, you have to recognize the regional signatures. Cantonese food is the "clean" one. You’ll see lots of steamed fish, ginger slivers, and light soy. The photos usually look brighter because the food itself isn't buried in oil.

Sichuan food is the opposite.

When you see pics of chinese dishes from the Sichuan province, the "star" of the photo is usually the oil. We call it la you. It shouldn't be thin; it should have body. If you see a photo of Laziji (Chongqing Spicy Chicken) and the chicken isn't literally buried in a mountain of dried peppers, it's probably not authentic. The "waste" in the photo—the peppers you don't actually eat—is what provides the visual context for the heat level.

Then there’s the "Wok Hei" or the breath of the wok. This is nearly impossible to photograph, but you can see its effects. Look for charred edges on wide rice noodles in a Beef Chow Fun photo. Those little black singe marks aren't "burnt" bits; they are the evidence of 500-degree heat. If the noodles look perfectly uniform and greasy without those marks, the kitchen probably lacked the heat necessary for true flavor.

The Lighting Trap in Modern Food Apps

A lot of people get fooled by "beautified" images on delivery apps. Most of those photos are generic stock images. If you see a photo of Kung Pao Chicken and the peanuts look perfectly spherical and the chicken is in perfect cubes, it’s a factory-made stock photo.

Real Kung Pao chicken is chaotic.

The peanuts are often halved, the leeks are cut at odd angles (the diamond cut), and the sauce should be "clinging" to the meat, not pooling at the bottom of the plate. This is a technical culinary term called bao zhi. It means the starch slurry has successfully bound the flavors to the protein. If the photo shows a watery soup at the bottom, the chef didn't get the temperature right.

Why 2026 is the Year of "Ugly" Food Photography

We are seeing a huge shift in how people document food. The "perfect" overhead shot is dying. People are moving toward high-flash, "ugly" photography because it feels more honest. When you see pics of chinese dishes taken with a harsh flash in a cramped stall in Xi’an, you can see the texture of the Biang Biang noodles. You can see the rough edges where the dough was ripped by hand.

That’s what you want.

- Look for Steam: If there's no steam or "haze" in the photo, the food was likely cold when the picture was taken.

- Check the Oil Color: Bright orange usually means fresh chili oil. Dark, brownish-red means the spices have been toasted or the oil has been reused—which actually can mean more depth of flavor.

- The Bone Factor: Authentic Chinese poultry dishes (like White Cut Chicken) are almost always served bone-in. If the photo shows perfectly boneless breast meat, it’s been Westernized.

How to Take Better Photos of Your Own Meal

If you're trying to capture your dinner, stop trying to make it look like a magazine.

First, get close. Like, really close. Use a macro lens if you have one. Chinese food is all about texture—the crunch of the wood ear mushroom, the silkiness of the silken tofu, the crisp skin of a Peking duck.

Second, don't use the overhead "flat lay" style. It flattens the 3D beauty of a piled-high stir-fry. Shoot from a 45-degree angle. This captures the height of the dish. A pile of Gan Bian Si Ji Dou (Dry Fried Green Beans) should look like a mountain, not a green smudge on a white plate.

Third, look for the "shimmer." The gloss on a well-executed glaze should reflect the light. If it looks matte, it’s dry.

The Evolution of the "Visual Feast" in Chinese Culture

Historically, Chinese cuisine focused on the "Three Essentials": Color (Se), Aroma (Xiang), and Taste (Wei). Color always came first. But "color" didn't mean "looks like a filter." It meant the natural vibrancy of the ingredients.

In the Ming and Qing dynasties, presentation was about symbolism. A dish might be arranged to look like a phoenix or a flower. Today, that's mostly reserved for high-end banquets or "state dinner" style cooking. For the rest of us, the visual appeal is about the "generosity" of the plate.

A "good" photo of a Chinese meal should look crowded.

Abundance is a core cultural value. A single, lonely plate in the middle of a vast table looks "poor" in a traditional Chinese context. When you search for pics of chinese dishes, the most authentic-feeling ones are often those showing a "lazy Susan" turntable packed so tightly you can’t see the wood of the table. This is the renao—the "hot and noisy" atmosphere that defines Chinese dining.

Hidden Details You Probably Missed

Notice the garnish.

In cheap takeout photos, it's always a sprig of curly parsley. That’s a dead giveaway of a non-authentic kitchen. In real pics of chinese dishes, you’ll see scallion threads (often soaked in ice water to make them curl), cilantro, or toasted sesame seeds. In some regions, like Yunnan, you might even see edible flowers or fried mint leaves.

And look at the rice.

If the rice is in a perfect dome, it was packed into a bowl and flipped. That’s fine, but "real" rice in a family setting is usually served loosely. The grains should be distinct. If they look like a mushy paste, the water-to-rice ratio was off, and the meal's foundation is compromised.

How to Spot a "Fake" Dish in Social Media Photos

We've all seen them. The "Chinese" dishes that look suspiciously like Panda Express. There's nothing wrong with American-Chinese food—it’s its own valid cuisine—but if you're looking for the real deal, the photos will tell on themselves.

- The Broccoli Test: Broccoli is not native to China. While it’s used now, traditional dishes usually use Gai Lan (Chinese broccoli) or Bok Choy. If the photo is 50% oversized florets of Western broccoli, it’s a Westernized adaptation.

- The "Glaze" Thickness: If the sauce looks like thick, translucent Jell-O, it’s overloaded with cornstarch. Authentic sauces are usually thinner or so well-incorporated that they aren't "drippy."

- The Color of the "Red": If a "spicy" dish is neon red (like Maraschino cherry red), it’s food coloring. Real chili heat is a deep, earthy crimson.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Food Adventure

If you want to find the best Chinese food in your city using photos, stop looking at the official restaurant gallery. Go to the "User Photos" section on Yelp, Google Maps, or TripAdvisor.

✨ Don't miss: Why Love Better Than Immortality Is Actually The Only Way To Live

Filter for the most recent ones.

Look for the "messy" shots. Look for the photos where the lighting is bad but the food looks "busy." If you see a photo of a fish head buried in chopped salted chilis (Duo Jiao Yu Tou) and the oil looks like it's still shimmering, you’ve found the right spot.

When you get to the restaurant, don't just point at a picture on a menu. Ask the server what the "specialty" is, then look up that specific dish's name in Chinese on a search engine. Compare the pics of chinese dishes you see on your phone to what is being served at the next table.

Consistency is key.

If the dish at the next table looks wildly different from the "hero shot" on the wall, the kitchen is taking shortcuts. You want to see the "imperfections"—the hand-pulled irregularities in the noodles, the uneven char on the clay pot rice, and the scattered herbs that weren't placed with tweezers.

That’s where the flavor lives.

Next time you see a photo of a Chinese feast, look past the filters. Look for the steam, the "breath" of the wok, and the beautiful, delicious mess of a meal shared with friends. That’s the real art of Chinese cuisine.

To truly master this, start by identifying three regional styles—Sichuan, Cantonese, and Shanghainese—and compare how they use "dark" vs "light" sauces in photos. You'll quickly develop an eye for what’s authentic and what’s just for show. Use your phone's "Portrait" mode with caution; it often blurs out the very textures that tell you if a dish is crispy or soggy. Instead, go for natural light and a tight crop on the protein. This highlights the "gloss" that indicates a fresh, high-heat stir-fry.