History isn't just a list of dates. It’s what we see. When you look at pics of hiroshima and nagasaki, you aren't just looking at old black-and-white photography; you're looking at the moment the world shifted on its axis.

August 1945. Most of us have seen the mushroom clouds. They’re iconic in the worst way possible. But those wide shots from miles away don't tell the whole story. Honestly, they’re almost too clean. They hide the grit, the melted roof tiles, and the shadows burned into stone. If you really want to understand what happened, you have to look closer at the ground-level stuff that the censors tried to keep quiet for years.

The Photos the Public Didn't See for Decades

Right after the bombings, the U.S. military occupation forces were pretty strict. They basically put a lid on anything that looked "too graphic." This wasn't just about security. It was about controlling the narrative of the new Atomic Age.

Take the work of Yoshito Matsushige. He was a photographer for the Chugoku Shimbun. On August 6, 1945, he was in Hiroshima. He had his camera. He actually took only five pictures that day. Can you imagine? Five. He later said he couldn't bring himself to press the shutter more than that because what he saw through the viewfinder was too heartbreaking. One of his most famous pics of hiroshima and nagasaki history shows survivors at the Miyuki Bridge, huddled together, clothes literally burned off, looking completely dazed. It’s grainy. It’s blurry. It is the most honest thing you will ever see.

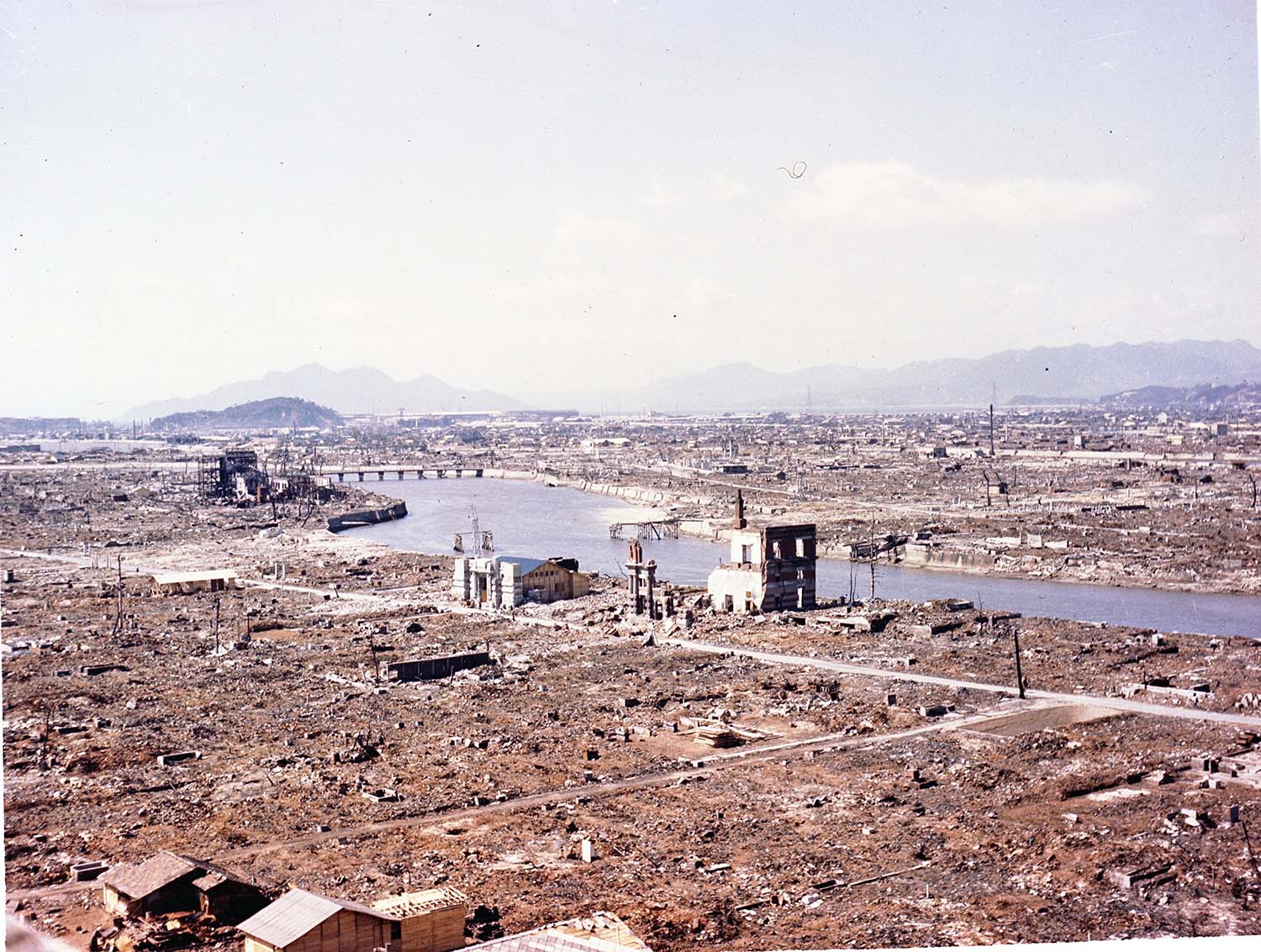

For years, the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey moved in and took thousands of technical photos. They wanted to see how concrete stood up to a nuclear blast. They weren't focused on the human element; they were focused on the engineering of destruction. These photos are clinical. Cold. You’ll see a building standing perfectly fine while everything around it is dust. This led to the "Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall" becoming what we now know as the A-Bomb Dome.

📖 Related: The World Series Earthquake San Francisco Still Remembers: What Really Happened at Candlestick

Why the "Nuclear Shadows" are So Disturbing

One of the most frequent things people search for when looking at pics of hiroshima and nagasaki is the "shadows." It sounds like something out of a horror movie. Basically, the thermal radiation from the blast was so intense that it bleached everything in its path. If a person was sitting on a set of stone steps, their body blocked the radiation. The stone around them turned white, but the stone behind them stayed dark.

The person was vaporized or killed instantly, but their "shadow" remained.

There is a famous photo of the Sumitomo Bank Hiroshima Branch. You can see the dark silhouette of a person who was waiting for the bank to open. It’s a permanent record of a split second. Looking at these images today, you realize these aren't just "pics"—they are forensic evidence of a level of heat we still struggle to wrap our heads around.

The Difference Between the Two Cities in Pictures

People tend to lump these two events together. But the pics of hiroshima and nagasaki show two very different tragedies. Hiroshima was flat. The bomb, "Little Boy," exploded over a level city center. The damage was circular and nearly total. When you look at aerial shots of Hiroshima, it looks like a giant took a vacuum to the earth.

Nagasaki was different. "Fat Man" was a plutonium bomb, actually more powerful than the uranium one dropped on Hiroshima, but the geography of Nagasaki saved lives. It’s a city of hills and valleys. The bomb exploded over the Urakami Valley. If you look at the photos of Nagasaki, you’ll see one side of a hill completely scorched and the other side relatively intact.

The Urakami Cathedral is a huge focal point in Nagasaki photography. It was the largest Christian church in East Asia at the time. The photos of its ruins—broken stone saints and collapsed arches—became a symbol for the survivors. It felt personal in a way that the destruction of military factories didn't.

The Color Photography of 1945

Wait, there’s color? Yeah. A lot of people don't realize that some of the most striking pics of hiroshima and nagasaki were actually shot on color film by Lieutenant Robert L. Capp and others. For a long time, we only saw the "official" grainy black-and-white versions in history books.

When you see the rust-red of the scorched metal and the weirdly bright blue sky over the ruins, it hits differently. It stops being "history" and starts looking like something that could happen today. The color photos show the "black rain"—sooty, radioactive water that fell from the sky after the blasts. Survivors thought it was water to drink because they were so thirsty from the heat, but the photos of the staining on the walls show just how toxic it really was.

The Censorship and the "Life" Magazine Reveal

The U.S. government actually confiscated a lot of film from Japanese photographers and news agencies. They didn't want the world to see the effects of radiation sickness. They called it "A-bomb disease" back then. It wasn't until the early 1950s, after the occupation ended, that magazines like Asahi Graphic began publishing the truly raw images.

In the States, Life magazine eventually ran photos that changed the public perception. They showed the keloid scars on the backs of survivors, known as Hibakusha. These weren't just burns. They were raised, thick scars that looked like nothing doctors had ever seen.

What Modern Photography Tells Us Now

If you go to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum today, the way they present these pics of hiroshima and nagasaki is very specific. They don't just show the explosion. They show the "before."

They show photos of kids at school. People at a festival.

Then they show the "after."

💡 You might also like: Is the $1702 stimulus payment 2025 actually real or just more internet noise?

It’s the contrast that kills you. You see a photo of a lunchbox with charred peas and rice inside. The photo of that lunchbox is just as famous in Japan as the mushroom cloud is in America. It belonged to a girl named Reiko Watanabe. She never came home.

Why We Keep Looking

Why do we keep searching for these images? Is it morbid? Maybe a little. But mostly, it’s because these pictures represent the "Great Divide" in human history. Before August 1945, we couldn't erase a city in seconds. After, we could.

The images serve as a visual deterrent. When political tensions rise, these photos start trending again. They remind everyone—leaders and regular people alike—of the actual, physical cost of "pushing the button."

The Ethics of Viewing

There is a big debate among historians about how we should view pics of hiroshima and nagasaki. Some say that showing the most graphic images is exploitative. Others argue that hiding them is a form of revisionist history.

If you look at the Shogo Yamahata collection, he took over a hundred photos in Nagasaki the day after the blast. He was sent by the Japanese military to document the damage. His photos are brutal. There’s no other word for it. But he insisted they be seen because he felt that if people didn't see the horror, they would be more likely to repeat it.

👉 See also: Who is the Presiding Officer in the Senate and Why Does It Matter?

Honestly, he was probably right.

Actionable Insights for Researching This History

If you are looking into this for a project, or just because you want to know the truth, don't just stick to Google Images. A lot of those are miscaptioned.

- Visit Official Archives: The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum have digitized much of their collections. These come with verified names and locations.

- Check the Shogo Yamahata Collection: For Nagasaki, his work is the definitive photographic record.

- Look for the Hibakusha Testimonies: Many survivors have paired their photos with oral histories. The "Atomic Heritage Foundation" is a great resource for this.

- Avoid "AI Enhanced" Versions: Recently, people have been using AI to upscale or "reimagine" these photos. Avoid them. They add details that weren't there and strip away the historical accuracy. The grain and the blur are part of the record.

Understanding these images requires more than a quick scroll. You have to look at the shadows, the rubble, and the faces of the people who were just trying to get to work or school on a Tuesday morning. The power of these photos isn't in the explosion; it’s in the silence that followed.

The best way to honor the history is to look at the photos as they are: uncomfortable, haunting, and absolutely necessary. Go to the primary sources. Read the captions. Don't look away.